Blog

The Unbundled Corruption Index (UCI): Prototyping a multi-dimensional measure

This blog is adapted from Yuen Yuen Ang, China’s gilded age: The paradox of economic boom and vast corruption. Copyright ©, Cambridge University Press (2020); reproduced with permission.

Standard indices of corruption – most notably, Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) – assign one score to each country and rank them annually. But measuring corruption on a single scale is misleading. First, these indices do not distinguish between different types of corruption. Second, while they capture brute and illegal acts of corruption that plague the poorest countries, such as bribery and looting of state assets, they tend to systematically overlook elite exchanges of power and wealth, which can be disguised, even legalised, in wealthy capitalist democracies.

As a result, when researchers plot CPI scores with income levels, poor countries appear riddled with corruption while rich countries look clean. But these results are clearly inconsistent with the outsized advantages enjoyed by the politically connected in high-income democracies, which has sparked public backlash. For example, as the New York Times revealed in 2020, half of UK government contracts for medical supplies during the COVID-19 pandemic went to ‘companies run by friends and associates of politicians’ through a special ‘VIP Lane’.

To provide an alternative to the likes of the CPI, in 2020 I prototyped a multi-dimensional measure of corruption: the Unbundled Corruption Index (UCI). Using a perception-based survey of regional experts, the UCI measures four distinct varieties of corruption: petty theft, grand theft, speed money, and access money.

Unbundling corruption into four types

I propose a typology along two dimensions: (i) corruption with exchanges vs corruption involving theft, and (ii) corruption involving elites vs corruption involving non-elites. That generates a matrix of four categories:

- Petty theft refers to acts of stealing, misuse of public funds, or extortion among street-level bureaucrats.

- Grand theft refers to embezzlement or misappropriation of large sums of public monies by political elites who control state finances.

- Speed money means petty bribes that businesses or citizens pay to bureaucrats to get around hurdles or speed things up.

- Access money encompasses high-stakes rewards extended by business actors to powerful officials, not just for speed, but to access exclusive, valuable privileges.

Whereas petty theft, grand theft, and speed money are almost always illegal, access money can encompass both illegal and legal actions. Illegal forms of access money entail large bribes and kickbacks – common in China – but they can also include ambiguously or completely legal exchanges that omit cash bribes, for example, cultivating political connections, campaign finance, ‘revolving door’ practices (moving between leadership posts in private and public sectors), and influence peddling.

Like drugs, all corruption harms but in different ways. Petty theft and grand theft are equivalent to toxic drugs; they drain public and private wealth. Speed money is like painkillers: although they lessen pain, they don’t give health benefits. Access money, on the other hand, is the steroids of capitalism. Steroids are known as ‘growth-enhancing’ drugs, but they come with serious side effects. Access money can distort the allocation of resources, breed financial risks, and exacerbate inequality. Their harms tend to blow up only in the event of a crisis (think the 1997 East Asia financial crisis or 2008 US financial crisis).

Table 1. Analogous to drugs, all corruption harms but in different ways

| Theft or exchange | Elites or non-elites | Legality | Economic effects | Analogy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Petty theft | Theft | Non-elites |

Illegal |

Growth-damaging |

Toxic drugs |

| Grand theft | Theft | Elites | Illegal | Growth-damaging | Toxic drugs |

| Speed money | Exchange | Non-elites | Illegal | Shortens delays but imposes cost | Painkiller |

| Access money | Exchange | Elites | Illegal and non-illegal | Stimulates growth but generates distortions, risks, and inequality | Steroids |

Source: Reprinted from Table 1.1. in China’s gilded age.

By collecting survey responses based on my framework of ‘unbundling corruption’, the UCI allows us not only to compare aggregate levels of corruption across cases, but more significantly, their composition.

Methodological innovations in the UCI

The UCI features a few methodological innovations. First, it makes a targeted attempt to measure the elusive category of access money – the purchase of lucrative privileges, both illegal and legal. A second innovation is using stylised vignettes to more accurately capture perceptions of corruption.

Existing surveys (that the CPI assembles to create its scores) ask respondents to assess corruption in broad terms, for example:

Rate: state capture by narrow vested interests

Are there general abuses of public resources?

Any of these statements can be interpreted in multiple, even conflicting, ways. This presents a validity problem: vaguely worded questions do not measure what they claim to measure.

To improve measurement validity, my survey asks respondents to evaluate corruption using stylised vignettes, designed to be concrete and yet generic enough to represent a class of similar corrupt activities. The vignettes are based on real events reported in scholarly work or the media.

For example, inspired by the saga of the Chinese politician Bo Xilai, one question captures ‘crony capitalism’ in this way:

By cultivating close ties with a powerful official and paying for his family’s expenses, a businessperson gains monopoly access to public construction projects.

How common do you think this type of scenario is in [country] today?

Previous studies use vignettes to ‘anchor’ respondents with potentially divergent understandings of survey questions. My vignette-focused survey is similarly designed to overcome cultural and other biases regarding what constitutes corruption, a perennial challenge in measuring corruption.

Visualising the UCI

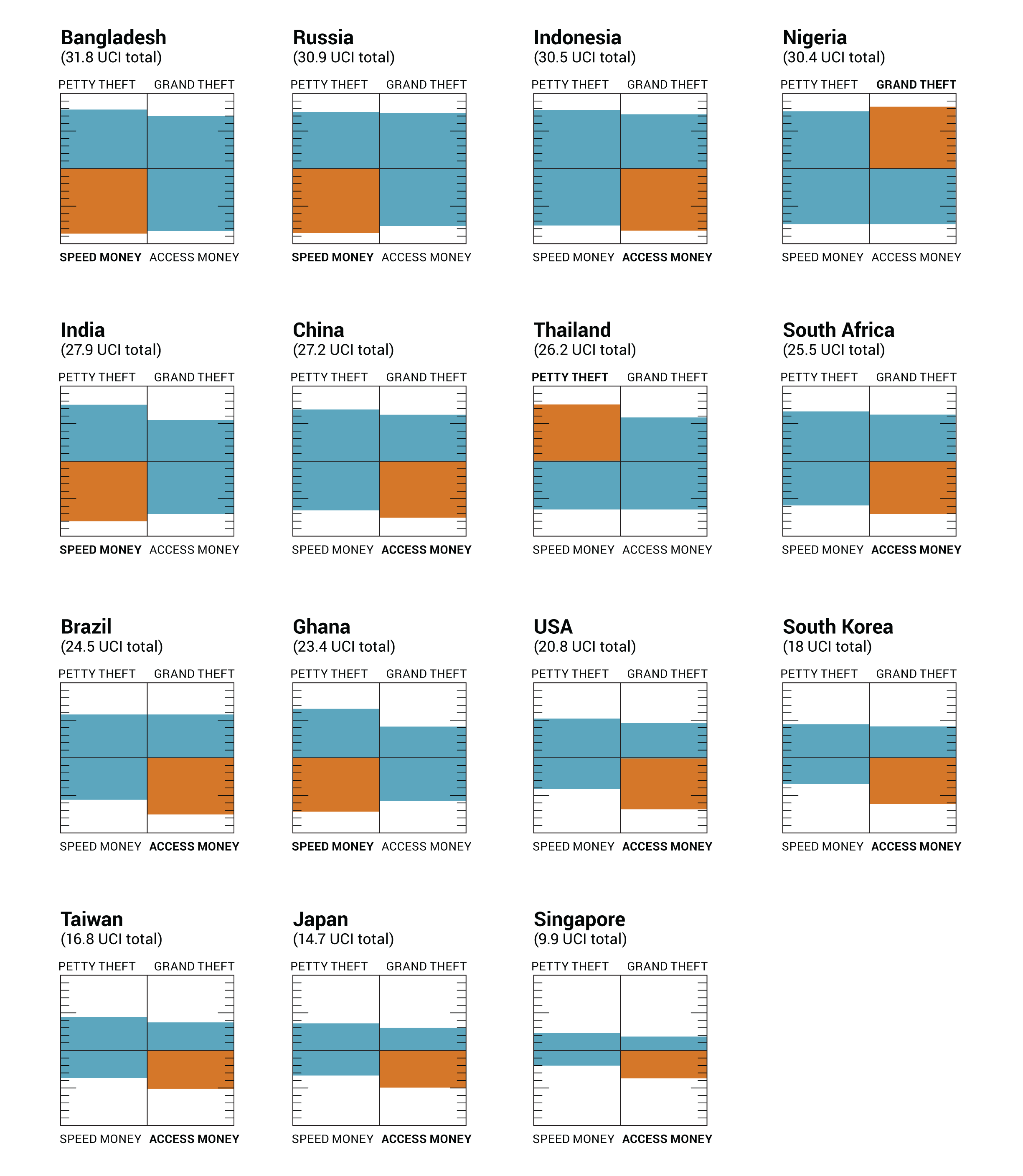

The figure below visualises the UCI in four typological clusters (petty theft, grand theft, speed money, access money), with 10 indicating the highest perceived level of corruption. The sum of the four categories is the UCI total score, which ranges from 0 to 40. The category that takes up the highest proportion of the score is interpreted as the dominant mode of corruption, shaded in orange.

Figure 2. Unbundled Corruption Index (UCI): Score and rank of 15 cases

Source: Reprinted from China’s gilded age.

Credit: Cambridge University Press (2020); reproduced with permission. copyrighted

Systematic qualitative comparisons: The case of China

The UCI advances systematic qualitative comparisons. Even experts can have vastly different opinions on corruption in a given country. Consider two competing characterisations of Chinese corruption.

- ‘Corruption in China was similar to many of the worst examples of endemic and economically destructive corruption elsewhere in the developing world.’ (Andrew Wedeman, Double paradox, 2012).

- ‘Corruption in China helped to navigate around excessive regulations and controls in an overly centralized bureaucracy’ (Yukon Huang, ‘The truth about Chinese corruption’, 2015).

Which of these conflicting descriptions is correct? Through stylised vignettes that focus and structure expert responses, the UCI provides a systematic basis for evaluating these statements objectively.

I highlight three comparative patterns suggested by my analysis of the UCI (for more details, see China’s gilded age):

- The structure of corruption matters as much as the overall level of corruption. Corruption in China is less damaging than in Russia because of divergence in composition. Both countries are rife with cronyism, but China has lower levels of those types of corruption that directly stifle growth: speed money, petty theft, and grand theft.

- Regime type affects which type of corruption dominates. In China’s one-party state, capitalists court politicians for their power to make sweeping decisions, whereas in India’s fragmented democracy, state actors extract rents by blocking approvals. Hence, bribery assumes different dominant forms in the two developing countries (access money in China vs speed money in India).

- Not all systems of access money are the same. Compared to institutional corruption in the United States, China’s style of access money is crude in that elite exchanges are enmeshed with personal relationships, mostly illegal, and still involve bribes.

The next step: UCI 2.0

At Johns Hopkins University, I am currently working on an improved and expanded UCI 2.0 to cover more variations of the four types of corruption, particularly the ambiguous category of access money. You can find details on our Unbundled Corruption Index webpage.

To learn more about the UCI, you can also listen to my podcast on Freakonomics Radio (Is the US really less corrupt than China?), watch a video lecture (Unbundling corruption and China’s gilded age), or read my oped at Project Syndicate (Mismeasuring corruption).

Hundreds of expert respondents who generously shared their time and country-level knowledge make the UCI possible. I’d like to take this opportunity to thank them for supporting our research efforts!

Anti-corruption measurement series

This blog series looks at recent anti-corruption measurement and assessment tools, and how they have been applied in practice at regional or global level, particularly in development programming.

Contributors include leading measurement, evaluation, and corruption experts invited by U4 to share up-to-date insights during 2024–2025. (Series editors are Sofie Arjon Schütte and Joseph Pozsgai-Alvarez).

Blog posts in the series

- One year on: The Vienna Principles for the measurement of corruption (Elizabeth David-Barrett) 2 Sep 2024

- Measuring progress on Sustainable Development Goal 16.5 (Bonnie J. Palifka) 1 Oct 2024

- Pitfalls in measuring corruption with citizen surveys (Mattias Agerberg) 11 Nov 2024

- Decoding corruption: using the DATACORR database to design better survey questions (Luís de Sousa, Felippe Clement, Gustavo Gouvêa) 25 Nov 2024

- Can we standardise global corruption measurement? (Salomé Flores Sierra Franzoni) 12 Dec 2024

- Assessing the quality of corruption surveys for SDG 16.5 monitoring and beyond (Giulia Mugellini) 27 Jan 2025

- (This post) The Unbundled Corruption Index (UCI): Prototyping a multi-dimensional measure (Yuen Yuen Ang) 4 Mar 2025

Sign up to the U4 Newsletter to get updates, or follow us on Linkedin.

Disclaimer

All views in this text are the author(s)’, and may differ from the U4 partner agencies’ policies.

This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)