Query

What evidence is there on illicit financial flows stemming from the mining sector in Liberia? What are the impacts of these on the economy? What are the potential mitigation measures?

Caveat

Illicit financial flows (IFFs) have been defined as ‘financial flows that are illicit in origin, transfer or use, that reflect an exchange of value and that cross-country borders’ (UNCTAD and UNODC 2020). While the definition encompasses a range of illicit activities, this Helpdesk Answer focuses on IFFs linked to corruption, that is where IFFs constitute proceeds of corruption or other illicit activities that are facilitated by corruption. Nevertheless, some of the literature cited may employ the term referring to a broader set of activities not necessarily linked to corruption.

Background

The Republic of Liberia is located on the West African coast with a population of around 5.5 million people. Its poverty rate currently stands at 35.4%, with rising domestic food prices and global fuel prices causing notable impacts on its population (AfDB n.d.). Liberia’s mining sector is a key driver of its economy, which contributed approximately US$621.80 million to its gross domestic product (GDP) in 2023 (bne IntelliNews 2025; Trading Economic n.d.).

Extensive tracts of land are the subject of concession and licensing agreements for industrial mining of iron ore, gold and diamonds. These minerals are also mined through actors engaged in artisanal and small-scale (ASM) mining practices. Iron ore, gold and diamonds constitute the most lucrative deposits in the country and among the most valuable mining exports (see Table 1).

Table 1: Exports of minerals from Liberia in 2023

|

Export |

Gold |

Iron ore |

Diamond |

|

Amount |

871 (million USD) |

393 (million USD) |

18.3 (million USD) |

|

Percentage of Liberia’s GDP |

36.9% |

16.7% |

0.77% |

|

Primary destinations |

Switzerland (81.2%), Lebanon (12%), United Arab Emirates (6.69%) |

France (29.6%), Germany (21.9%), Poland (12.7%), Spain (12.4%), China (12.1%) |

United Arab Emirates (UAE) (43.8%), Belgium (43.6%), India (4.83%)* |

* The Global Organized Crime Index notes that the illegal diamond trade in Liberia is ‘dominated by Lebanese families with connections to the UAE and Belgium’ (Spatz 2024:4).

Source: OEC 2023

In January 2025, President Joseph Boakai announced the discovery of new mineral deposits, including uranium, lithium, cobalt and manganese, which he claimed could attract US$3 billion in investments (Poquie 2025).

Every year, an estimated US$88 billion is lost from the African continent through illicit financial flows (IFFs)9156fe7641f1 (UNCTAD 2020). The High-Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows identified a clear correlation between high dependency on the extractive industries and the incidence of IFFs in Africa (UNECA 2015:67). IFFs divert funding away from areas critical to development such as social services, infrastructure and investment (UNECA 2015). Research also shows that IFFs lead to flight-driven external borrowing, which in turn triggers debt-fuelled capital flight, compounding government indebtedness (UNCTAD 2020:34). UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD 2020:40) estimates that IFFs stemming from extractive industry exports in Africa account for around US$40 billion, with 77% of these stemming from gold, 12% from diamonds, 6% from platinum and 5% from other extractive commodities.

IFFs manifest through multiple illicit activities, including corruption, money laundering, tax evasion, trade mispricing (also known as trade misinvoicing) and illicit resource extraction (OECD 2020:9; CENTAL 2017). In the extractive industries specifically, IFFs occur through corruption, illegal exploitation and tax evasion (ACEP 2015:2).

West Africa is one of the regions (along with Central Africa) that is estimated to be the largest exporter of illicit capital in the continent (AFDB and GFI 2013). While there is sparse evidence on the exact amount of IFFs stemming specifically from the Liberian mining sector, evidence suggests that minerals such as gold are smuggled out of the country at significant rates each year (OECD 2020:9).

Liberia currently ranks 135 out of 180 countries on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, placing it near the bottom in terms of public sector corruption globally (Transparency International 2025). In 2023, 76% of Liberian respondents interviewed for the Afrobarometer believed that corruption levels had increased, and 88% rated the government's anti-corruption efforts as inadequate (AfroBarometer 2023). Foreign investors report that corruption is most pervasive in government procurement, mining concessions, customs and taxation, regulatory oversight, and public financial management (USSD 2023a). Finally, in terms of resource governance, the 2017 Resource Governance Index scored Liberia 52 out of the 89 assessed countries, with a particular emphasis on its low score on revenue management (30 out of 100) (NRGI 2017).

Both corruption and IFFs are a significant barrier to economic development and the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The natural resource endowment of the African continent is considered to be a potential driver of the investments needed in the region for development (ACEP 2015:3). However, given that a vast percentage of the region’s resources is being lost through IFFs, this considerably undermines the continent’s development (ACEP 2015:3).

This Helpdesk Answer reviews the wider evidence on corruption IFFs in Liberia’s mining sector, focusing primarily on IFFs that stem from the proceeds of corruption or other illicit activities that are facilitated by corruption. The paper explores various key aspects of corruption and IFFs in mining in Liberia, then considers its wider impacts, before drawing from best practices from across the region on potentially relevant mitigation measures.

Risk factors in Liberia

Liberia’s mining sector is riddled with collusion, extortion, facilitation payments, bribery, abuse of power, and vested interests throughout the value chain (CENTAL 2017). These forms of pervasive and entrenched corruption, combined with other factors, create an enabling environment for IFFs stemming from the mining sector. This section explores the key aspects of these dynamics in Liberia and the areas of risk that could enable IFFs stemming from the mining sector. However, it should be noted that the evidence on IFFs from Liberia’s mining sector is sparse and relatively under-researched.

Institutional vulnerabilities

In Liberia, weak legal and institutional frameworks may enable corruption in the mining sector, potentially leading to the generation of IFFs. For example, the Ministry of Lands, Mines and Energy (MLME) is the government agency responsible for the administration of the mining sector, but its mandate overlaps with some other bodies, including the Liberia Revenue Agency, which collects all mining company fees. Limited intelligence sharing between responsible bodies is reportedly an issue, hindering effectively monitoring contractual compliance or adjusting policy (Global Delivery Initiative 2019:2). The curtailed reach of these administrations in remote areas has also meant that small-scale miners have had to travel to the capital for licensing, which left some remote areas effectively unregulated (Global Delivery Initiative 2019:2).

The Ministry of Justice acknowledges that weak enforcement and legal loopholes allow illicit activities to persist (Ministry of Justice, Republic of Liberia 2022: 28). For example, legal loopholes and poor enforcement of licensing and concession arrangements allow corrupt actors to manipulate contracts, evade taxes and siphon off mineral wealth (MineHutte 2025; CENTAL 2017). Due diligence in reviewing applications and properly scrutinising draft concession agreements is reportedly weak and ineffective, with the poor deals being made (CENTAL 2017:7). The Global Organized Crime Index (Spatz 2024:4) also notes that government oversight of the Liberian mining sector is weak and marked by nepotism and political indifference with the rise of illicit mining due to a lack of enforcement of mining laws.

In terms of anti-money laundering, the Financial Action Task Force’s (FATF) 2023 mutual evaluation highlighted similar concerns that interagency information sharing can be improved as well as the need for further progress regarding operational cooperation and coordination among anti-money laundering supervisory authorities (FATF 2023:54). For example, the report mentions that the Financial Crimes Working Group (FCWG) which provides a platform for key stakeholders, including the Financial Intelligence Agency, Liberia Anti-Corruption Commission, Liberia Revenue Authority, Customs, police and immigration to cooperation on intelligence and information sharing on financial crimes (FATF 2023:53). While the FCWG has had some success in coordination and information sharing, the FATF recommends that “further progress is needed regarding operational cooperation and coordination amongst supervisory authorities while there is no operational cooperation for proliferation financing” (FATF 2023:54).

Domestic political actors

Private actors in the mining sector may seek to influence Liberia’s political decision-makers, including through bribery and other forms of corruption, as a means for gaining favourable treatment. Acts of international bribery in lower-income countries such as Liberia can involve transfers in or out of the country of origin, generating substantial outflows of IFFs (OECD 2014). Political elites could also serve as intermediaries for multinational mining ventures, facilitating IFFs through obscuring the ownership and transferring funds to offshore entities (FATF 2021b:11-25; McDevitt 2024: 13-19).

In Liberia, these risks appear pronounced. For example, the MLME has faced allegations that it is subject to the influence of mining cartels, particularly those controlled by foreign individuals (Harmon 2024). As a result, illicit mining activities were reportedly operating in several areas of the country, resulting in pollution of the environment and water sources along with potential tax evasion (Harmon 2024). This entrenched corruption has led to attempts to reform the sector by the current political party in power, despite them acknowledging the difficulties in doing so (Harmon 2024).

Several recent high-profile cases have implicated domestic political actors. In 2010, top Liberian officials and judges were indicted for accepting over US$950,000 to amend mining laws in favour of a London-based firm (US Department of the Treasury 2020). In 2023, the US State Department sanctioned Liberia’s minister of finance and two senators for ‘soliciting, accepting, and offering bribes to manipulate legislative processes and public funding, including legislative reporting and mining sector activity’ (USSD 2023b).

Business actors

In Liberia, the mining sector is dominated by large international mining companies, which hold significant influence. For example, the illicit diamond trade in Liberia is reportedly ‘dominated’ by Lebanese business families who have longstanding financial and commercial ties to Belgium and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) – two of the world’s largest diamond trading hubs (Spatz 2024).

Mining companies and government officials in the wider African region have adopted creative and innovative solutions to circumventing legislation that is designed to curb IFFs (Mutio 2021:87). They have manipulated rules and exploited weaknesses in existing legal systems. The involvement of multiple actors (such as public officials, national and multinational companies, and intermediaries), the high sum of profits generated, the opacity and secrecy, make the sector particularly vulnerable (Mutio 2021:88). Business investment initiatives created in the African region to attract overseas direct investment in the sector are not aligned with domestic mobilisation objectives (Mutio 2021:92).

These may create supply for corruption in the sector in the form of foreign bribery (OECD 2018b:3). Many large multinationals have been accused of engaging in corruption in Liberia. An investigation by Global Witness (2019; 2016) using leaked documents alleged that the South African company Sable Mining spent hundreds of thousands of dollars bribing top political officials in Liberia, which led it to be granted an export permit; the investigation alleged that professional enablers, including a lawyer, based in London where the company’s stock was also listed, may have facilitated the payments. Nevertheless, the accused political officials denied the charges and were acquitted by a Liberian court in 2019 (Global Witness 2019).

In 2024, following an investigation by a ministry into allegations of illicit mining activities, the owners of a China registered company were indicted for economic sabotage, tax evasion and criminal conspiracy related to allegedly running a criminal cartel in the Liberian mining sector, resulting in estimated losses of US$20 million (Front Page Africa 2024). Other sources have argued that a Chinese national considered to be the figurehead behind the company carries undue influence over the governance of the mining sector in Liberia, deeming him the ‘real minister’ (Harmon 2024). As of March 2025, the case had not proceeded to a court trial.

Companies exploit loopholes through partnerships between foreign companies and local companies. Some legislation is designed so that only local companies can operate in the country, but foreign companies circumvent this through establishing a consortium with local companies who are ultimately owned by government officials to win the bidding process for licences (Mutio 2021:94). While there is no evidence which explicitly mentions this tactic in Liberia, the Liberian government has been known in the past to retroactively negotiate better contract terms with foreign companies such as ArcelorMittal and Firestone (Kaul and Heuty 2009:1).

Both domestic political and business actors in Liberia may exploit transnational ownership structures of legal entities and arrangements, including the protections offered by secrecy jurisdictions.926cb0b42f2f There is evidence from the wider African region which shows how opaque corporate structures and shell companies are misused to move and conceal the proceeds of money laundering, tax evasion, grand corruption, bribery and drug trafficking (see e.g. Rocha-Salazar, 2022; McDevitt 2024; van der Does de Willebois, 2011).

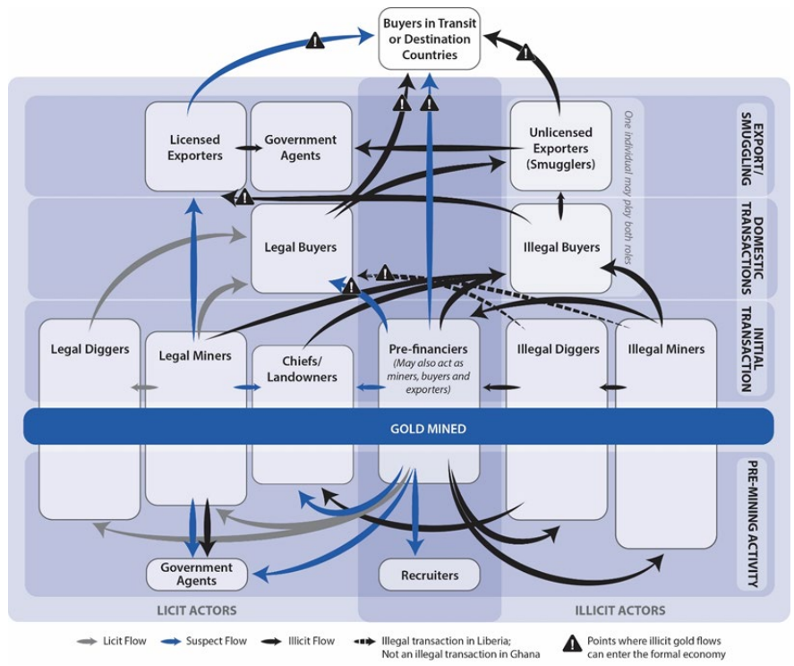

In Liberia, evidence from the OECD suggests that revenues generated from illicit mineral exports are often laundered through offshore accounts, foreign real estate investments and opaque corporate structures, making them difficult to trace (OECD 2020:42-44). The report identifies the United Arab Emirates and Switzerland as the primary transit points for West African gold (OECD 2020:40). Some of the laundered funds may also then be roundtripped back into Liberia via under-invoicing of imported goods (GFI 2015:43). The OECD (2020:25) illustrates the complexity of these schemes (in relation to artisanal and small-scale gold mining) in Figure 1:

Figure 1: Financial flows related to artisanal and small-scale gold mining in Ghana and Liberia:

Source: OECD 2020:25.

These schemes often reveal ties to secrecy jurisdictions. The West African investigative journalism outfit CENOZO published an article alleging that a British businessman created a company registered in the Seychelles that nominally described itself as active in commodity trading and mining in Liberia, but in reality, was a shell company used for tax evasion purposes (CENOZO 2021). CENOZO (2019) also carried out an investigation into a Lebanese owned but Liberian registered gold firm called Golden Vision Trading. Between 2012 and 2013, they allegedly sent and received suspicious and payments to a Dubai company that was under investigation in the United States for money laundering.

An investigation by Freudenthal and David (2017) into Liberia’s first industry-level gold mine – New Liberty Gold – argues that Aureus Mining, the main company operating the mine, was part a of a network of shell companies, many of which were recently named in the Panama Papers leak and registered in secrecy jurisdictions.

Artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM)

Some authors have highlighted the prevalence of cash transactions and the large size of the informal sector as corruption and IFFs risk factors in the mining sector in African countries (McDevitt 2024; FATF 2021b:54).

In Liberia, these risks are acute, particularly in artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM). The Liberia Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (LEITI)’s 2015 scoping study estimated that Liberia had approximately 100,000 artisanal and small-scale miners and up to 500,000 diggers engaged in informal mining activities. Nevertheless, the sector remains largely unmonitored, contributing to high levels of smuggling, corruption and tax evasion (DELVE 2021). Furthermore, CENTAL (2017) found that the lack of traceability mechanisms in gold exports allows smuggled gold to bypass official taxation and accountability measures.

Similarly, the OECD (2020:20) found that key institutional weaknesses enabling IFFs in ASM include the lack of mining inspection capacity as the responsible ministries struggle to legitimise and adequately resource mining inspectors, leaving much of ASM unregulated. The absence of gold traceability systems makes functional due diligence and traceability frameworks impossible to track from extraction to export (OECD 2020:47).

However, commentators also highlight that ASM is one of the main sources of livelihood for the majority of Liberians other than farming (Bazillier et al. 2023; Katz-Lavigne 2023). One estimate indicates that up to 1.575 million Liberians depend on ASM as a source of livelihood (Bazillier et al. 2023). Therefore, Katz-Lavigne (2023) calls for a more nuanced approach to ASM and notes that excessive criticism of the practice often serves the interests of big industrial mining companies who may not act in good faith (Katz-Lavigne 2023). Furthermore, the OECD notes that, in practice, the line between formal and informal mining is often blurred and, in Liberia, industrial miners who hold licences may still mine outside their allocated land (OECD 2020: 27).

Trade mispricing

A primary driver of IFFs in the sector is trade mispricing (or misinvoicing), the deliberate underreporting of mineral exports to evade taxes and transfer wealth offshore. This practice conceals predicate crimes such as tax avoidance, bribery and corruption (UNCTAD 2020). GFI estimates that, between 2004-202013, Liberia lost approximately US$8,288 million through trade mispricing across multiple sectors, including, but not limited to, mining (GFI 2015: 35). Another GFI estimate found that that underinvoicing of imports greatly surpassed that of exports in Liberia, indicating that IFFs could also be rerouted back to Liberia in significant quantities (GFI 2015:43).

Many mining actors in Liberia do operate within nominally legal concessions but then engage in illicit transactions, such as underreporting production volumes and tax evasion, facilitating significant IFFs through trade mispricing (OECD 2020:42). It has been argued that the overly bureaucratic nature of administration means there are numerous steps and opportunities for actors to engage in mispricing (Spatz 2024; OECD 2020:19-21).

Reports of distorted reporting of quantities have been widely detected in Africa, such as when companies declare lower-than-actual values for exported gold and iron ore to reduce taxable income, but also the overvaluation of mining equipment (UNECA 2015:27). Furthermore, multinational corporations reportedly engage in the manipulation of transfer pricing, artificially shifting profits to lower-tax jurisdictions by charging inflated service fees or underpricing intra-company mineral sales (UNECA 2015:27).

Liberian authorities responsible for enforcing export taxes and excise duties for minerals may be vulnerable to corruption. Risks of insufficient audit capacities, abuse of duty-free privileges, arbitrary tax concessions and poor oversight of the allocation of concessionary contracts have all been highlighted as recurrent issues in the country (Resimić 2021).

Land corruption

The lack of formal land tenure documentation in many mining areas in Liberia allows local power brokers, including chiefs and government officials, to sell land informally without oversight. Miners in other parts of West Africa have been found to have paid local leaders upfront or promise future profits in exchange for mining rights, bypassing official channels and taxation (Hunter and Smith 2017). The funds exchanged in these transactions often become part of IFFs as they are not recorded in formal accounts and are frequently diverted for personal gain rather than community development (Glencorse 2017).

Land access is often secured through unregulated payments, frequently disguised as bribes, which disproportionately benefit local elites and politically connected individuals at the expense of community development and state revenue. These off-the-books land deals facilitate unregulated resource extraction, enabling tax evasion, money laundering and corruption (OECD 2020:19-21). Furthermore, the absence of regulatory oversight reportedly allows criminal actors to use land acquisitions as a front for laundering mining proceeds into real estate and other sectors, further obscuring the origins of illicit wealth (Global Witness 2018).

This is compounded by reported corruption in the Liberia Land Authority (LLA), which has been accused of lacking the control mechanisms to effectively oversee land governance and administration (Davis 2024). Investigations have found that leasing or sale of land by the authority to prominent individuals and businesses have not followed the correct legal and procurement procedures (Davis 2024). It has been reported that the LLA’s chairman has been accused of using his position to amass personal wealth, despite him denying any wrongdoing (Davis 2024).

Smuggling networks

Smuggling networks occupy a prominent role in Liberia’s mining sector. Composed of local miners, traders and international intermediaries, they systematically avoid formal export procedures, enabling illicit sales and profit concealment. This enables the proceeds of corruption in the sector to leave the country in IFFs in the form of minerals. Smuggling can be enabled through corruption when, for example, customs and border authorities are compromised and accept bribes to compensate for poor salary levels, but also where political corruption leads to overall lax enforcement (GITOC 2023).

Cross-border smuggling is one of the most pervasive and significant risks of IFFs in the mining sector in Liberia. Gold, diamonds and other minerals are often illicitly exported through porous borders to neighbouring countries or beyond, where they are sold at much higher values, bypassing taxes, duties and regulatory controls and fuelling IFFs (OECD 2020:25-39).

It is estimated that up to 90% of gold mined in Liberia is illicitly exported, leading to substantial revenue losses amounting to hundreds of millions of dollars annually. Although Liberia produces an estimated 10 tonnes of gold per year, official government revenues fail to reflect this due to the entrenched presence of informal trade routes and criminal networks operating both domestically and internationally (OECD 2020:9). The 2019 national risk assessment on money laundering and terrorist financing, conducted by Liberia’s Ministry of Justice acknowledged the issue (Ministry of Justice, Republic of Liberia 2019:110):

‘unmonitored diamond and gold mining in border areas and opaque trading networks continue to be of concern’.

As an example, Sierra Leone introduced the Mines and Minerals Act in 2009 imposing export taxes of 5% on gold and 6.5% on precious stones; official gold exports dropped to zero in the subsequent six months, while neighbouring Guinea and Liberia saw a spike in their exports, suggesting cross-border smuggling (Akam 2012). Dubai is serving as a primary destination due to its minimal regulatory oversight and high-volume gold trading. The UAE’s lax due diligence requirements make it a preferred hub for illicit gold transactions, where smuggled gold is easily integrated into the formal market400a6fdeb100 (Spatz 2024). In addition to UAE, Switzerland and India are the top importers of African gold, accounting for both declared and undeclared gold (Ummel and Schulz 2024).

Professional enablers

In Liberia, a professional enablers industry of accountants, lawyers and dealers in precious minerals and metals play a crucial yet often unregulated role in the country’s mining sector. The involvement of accountants and lawyers in Liberia’s mining sector plays a dual role. While these professionals provide essential services, they can also knowingly or unknowingly facilitate money laundering. This is done through structuring financial deals that disguise the illicit origins of funds, managing transactions and processing payments with minimal regulatory oversight and establishing opaque corporate structures that enable illicit actors to move and conceal wealth (GIABA 2023:32). Intermediaries such as freight forwarders, insurers and customs brokers also contribute to financial transactions within the mining industry, making them possible key actors in IFFs (FATF 2021b:18).

The lack of an effective legal framework and weak enforcement of anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) regulations have left this sector highly vulnerable to financial crimes. Liberia’s Financial Intelligence Agency (FIA) has identified deficiencies in the country’s AML/CFT framework, particularly regarding the regulation of designated non-financial businesses and professions (DNFBPs). While DNFBPs face general customer due diligence requirements in Liberia, these do not prescribe a threshold for transactions or outline specific activities for different categories of DNFBPs, including lawyers and dealers in precious metals and stones (GIABA 2023: 193). This led Liberia to receive only a partially compliant rating for FATF Recommendation 22 on customer due diligence for DNFBPs.

Other key concerns highlighted include:

- absence of specific AML/CFT guidelines per type of DNFBP, leading to weak compliance and oversight

- a lack of designated AML/CFT supervisors for DNFBPs, creating enforcement gaps that allow illicit activities to flourish

- Reliance on cash transactions, making it difficult to track financial movements and increasing opportunities for money laundering (Ministry of Justice, Republic of Liberia 2019; GIABA 2023: 10; 20; 205).

Wider impacts

The centrality of Liberia’s mining sector to the country’s economy, and to wider regional and international mineral supply chains, means that corruption and IFFs in the sector can have major impacts and downstream harms. This section focuses on two of these wider impacts, on security and on the environment.

Security

IFFs can exacerbate existing fragility and conflict, such as when capital flight reduces the capacity of the state and society to tackle underdevelopment, inequality and political instability (Jenkins 2024).

In conflict-prone regions, insurgency groups and local warlords may be involved in the operation and derive financing from mining sites (Banchereau 2024; Usanov 2013). Following the end of Liberia’s civil war, over 100,000 ex-combatants, including approximately 11,000 child soldiers, were disarmed and demobilised (USIP 2010:2). However, many of these individuals have struggled with reintegration into society, leading them to seek alternative livelihoods, including involvement in illegal mining (USIP 2010:2). The intersection of illicit mining and Liberia’s conflict history has heightened security risks, particularly as former fighters turn to illicit activities.

The 2014 UN panel of experts report highlighted that ASM sites can serve as venues for recruitment and training, exacerbating security challenges in Liberia’s already fragile post-conflict environment (UNSC 2015). However, this finding is perhaps unsurprising given that ASM serves as one of the main sources of livelihood for Liberians, especially those from a background of socio-economic disadvantage.

Security risks are further compounded by the proliferation of the illicit arms trade connected to illegal mining operations and financed by IFFs. Foreign actors, including Ghanaian and Chinese miners, have reportedly procured weapons illegally from police officers to protect themselves and their mining operations (OECD 2020: 23).

IFFs can also exacerbate existing land disputes and conflicts, which can have violent ramifications. In Ghana and Liberia, land access payments in artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) occur before extraction, often through informal transactions that remain undeclared. Weak land tenure policies and geographical barriers further obscure ownership rights, impeding enforcement and regulatory oversight (OECD 2020: 29; UNCTAD 2020).

The mining sector is also a major driver of human trafficking. Revenues from illegal mines are generated through unregulated markets, generating massive illicit financial flows, which fuel organised crime networks specialising on human trafficking across the West African region (UNODC 2024). The Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Ghana, Burkina Faso, Chad, Uganda, Central African Republic, Kenya and Liberia are countries with the highest proportion of people exploited in the artisanal and small-scale mineral industry (UNODC 2024:70).

Environmental

The ‘low risk, high reward’ nature of environmental crime fuelled by IFFs and linked to mining makes for a lucrative and relatively safe source of illicit revenues (FATF 2021b). Corrupt regulators allow mining companies to bypass environmental safeguards, leading to unchecked pollution and ecosystem destruction. Illicit mining activities, particularly in the gold sector, contribute significantly to deforestation, biodiversity loss and pollution (OECD 2024: 20). In Liberia, the expansion of mining concessions has reportedly resulted in land dispossession, water scarcity and deforestation, further threatening local communities’ livelihoods (Paczynska 2016).

In West Africa, artisanal and small-scale gold mining is widespread, and illegal operators often use illicit funding to acquire harmful chemicals used in mining, such as mercury and cyanide, which pose significant environmental and public health risks (OECD 2020: 11). Freudenthal and David (2017) report that, in the aforementioned New Liberty Gold case, the mining operators accidentally released cyanide and arsenic into a river which reached several villages downstream, and that the parent company was eventually fined by the Liberian Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for disrupting an investigation into the leak.

In Liberia, environmental non-compliance is a significant corruption risk in its mining sector. Some mining companies operate without the necessary environmental permits, leading to widespread deforestation, water pollution and land degradation. In August 2024, the EPA shut down China Union’s Bong Mines for violations, citing illegal disposal of mining waste (Reuters 2024a).

Mitigation measures

The mining sector in Liberia and across Africa plays a pivotal role in economic development, yet it is simultaneously one of the sectors most vulnerable to corruption and IFFs. There are, however, some lessons from Liberia and the wider African region on the mitigation measures that can be leveraged.

As highlighted above, actors such as multinational companies domiciled in foreign jurisdictions are complicit in corruption and IFFs. This section focuses on measures which can be taken domestically in Liberia, as well as through regional partnerships, but notes that more enhanced oversight and enforcement by the governments of such jurisdictions would also be required to fundamentally address these issues.

Strengthening regulatory frameworks

Various commentators (CENTAL 2017; MineHutte 2025) argue for a stronger and updated regulatory framework in Liberia to contain the risks of corruption and IFFs, including stricter penalties for corruption, enforceable asset declarations and clear guidelines for mining concessions. The Ministry of Justice suggested that imposing severe penalties for non-compliance and ensuring full transparency in asset declarations would serve as a deterrent against corrupt practices (Ministry of Justice, Republic of Liberia 2019). The OECD (2020:47-48) has argued that for sanctions to be effective, they would need be enforced against actors along the entirety of the supply chain, from pre-financing to the mine, export, the refinery and the destination.

Liberia could also increase regulation of business actors in line with international standards like the OECD due diligence guidance for responsible supply chains of minerals from conflict-affected and high-risk areas. These clarify how companies can identify and better manage risks throughout the entire mineral supply chain, and some other African countries have already integrated the standards into their respective legal frameworks (OECD n.d.). This also holds true for the recommendations issued by the UN secretary-general’s panel on critical energy transition minerals (International Institute for Sustainable Development 2024), which may hold special relevance in the near future of Liberia given the recent discovery of uranium, lithium, cobalt and manganese deposits. There are other international standards covering different aspects of mining which can guide regulatory and policy frameworks in Liberia.c47f529f222d

Other sources argue in favour of extending AML/CFT regulations to introduce specific guidelines for DNFBPs operating in the mining sector. Establishing designated supervisory bodies to monitor compliance, reduce cash-based transactions and enforce due diligence requirements is a key precondition (FATF 2021a; GIABA, 2023). Ghana, a major gold producing country, extended AML/CFT measures to DNFBPs sectors, which have reportedly contributed to a gradual increase in transparency (FATF 2021a). The FATF recommendations (FATF 2012-2025: 20) state that dealers in precious metals and precious stones be required to report suspicious transactions when they engage in any cash transaction with a customer equal to or above a threshold of US$15,000. FATF (2020) also issues guidelines on addressing trade-based money laundering (TBML), which also addresses trade mispricing. This includes increasing the understanding of TBML risks among key actors, including financial intelligence units and customs authorities, and using tools to analyse trade-related transactions, such as customs cargo analysis (FATF 2020).

In the literature, several reports favour measures to formalise the informal mining sector by ensuring that mining operations adhere to regulatory standards. These include a comprehensive traceability framework to track the mineral from extraction to export, reducing the scope for smuggling and trade mispricing (OECD 2020: 47). A traceability framework could take the lessons and challenges of the Kimberley Process certification scheme (KP CSC) for diamonds to improve its impact (KPCSC, 2020; 2024). However, the KP CSC is not without its critics, with UN representatives describing it as a reactionary instrument, as opposed to an effective tool for the prevention of conflict diamonds being sold (Mtisi 2020). As such, local community representatives have recently been engaged in reform of the Kimberley Process to ensure that is it still relevant and appropriate today (Bamenjo 2024).

Furthermore, there could be increased integration of artisanal and large-scale mining operations and more cooperation between artisanal miners and larger mining companies through joint ventures and cooperative model (OECD 2020: 45; LEITI 2023). The Tanzanian government has introduced initiatives to streamline the licensing process for artisanal miners, provide financial and technical support, and implement digital registration systems (DELVE 2023). Similarly, there could be incentives provided for formalisation by offering financial and technical support to artisanal miners who register and comply with formal regulations. This support could include access to microfinance, capacity-building programmes and market links that promote fair trade practices (AfDB 2024).

However, other authors express scepticism about aspects of formalisation. Katz-Lavigne (2023) describes how large-scale companies often benefit more than citizens when ASM is undermined. Similarly, Bazillier et al. (2023) describe how formalisation efforts in Liberia have led to more expensive and bureaucratic licensing processes but have not necessarily addressed the labour concerns or environmental impacts of mining practices. They suggest that livelihood challenges and the demands of people at the centre of formalisation should be placed at the centre of any policy measures (Bazillier et al. 2023:13). Nhlengetwa (2025) similarly stresses the importance of a bottom-up approach and local needs assessment to ensure formalisation measures are sustainable.

Transparency measures

Transparency is essential to reduce IFFs by making it easier to track financial flows and hold corrupt actors accountable. Liberia launched a digital beneficial ownership register in 2023, which aims to increase business sector accountability, particularly in mining (LEITI 2023). However, meaningful progress reportedly remains hindered by weak enforcement, poor regulatory frameworks and financial opacity (Spatz 2024; CENTAL 2017). Strengthening the capacity of institutions like LEITI, the financial intelligence agency (FIA), and the Liberia Revenue Authority (LRA) to monitor mining activities and enforce regulations effectively is an important precondition (Ministry of Justice, Republic of Liberia 2022; Global Witness 2018).

Liberia Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (LEITI)

By becoming a member of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), countries commit to implement the EITI Standards, a common set of rules on disclosing information along the extractive industry value chain, including for oil, gas and minerals. In 2009, Liberia established the Liberia Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (LEITI) to implement the EITI standard. It publishes an annual report disclosing information on contracts and licences, production, revenue collection, revenue allocation and social and economic spending in the extractive sectors.

(Source: LEITI n.d.; EITI n.d.)

Digital traceability systems can significantly reduce opportunities for trade mispricing and smuggling by ensuring that each transaction is recorded and verifiable (PROFOR 2012; OECD 2020:46-47). For example, blockchain platforms, such as De Beers’ Tracr and Everledger in Botswana, have been deployed to track diamonds from the mine to the retailer. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, blockchain initiatives have been piloted to monitor the cobalt supply chain (Novethic 2018). Rwanda’s broader digital transformation efforts also offer a model for how blockchain technology could be extended to real-time tracking of mineral exports and associated financial transactions (SmartAfrica 2020).

Furthermore, implementing a digital land registry including information on beneficial ownership could help to ensure that all land transactions related to mining are transparent and legally recognised. This measure would limit the scope for unregulated payments and corrupt practices in land acquisition (Hunter and Smith 2017). Rwanda’s digital land registry and advanced e-governance systems have significantly improved the transparency of land transactions, reducing the scope for informal, unregulated deals that often underpin IFFs (Foon 2023:109).

Greater transparency in the sector can ultimately lead to more accountability. Investigative journalism and independent media have played a pivotal role in exposing corruption and IFFs and contribute to the mobilisation of law enforcement to act against illicit wealth accumulation. For example, in Nigeria, high-profile media investigations into oil sector corruption have led to convictions and recoveries of assets (Prusa 2024).

Regional cooperation

Developing and participating in regional agreements and frameworks to facilitate intelligence sharing, harmonise regulations and coordinate enforcement actions may significantly improve the detection, investigation and prosecution capacity of Liberian governmental institutions (UNECA 2015:83).

The African Union established the African Minerals Development Centre (AMDC) by statute in 2016 to implement the Africa Mining Vision to enable the minerals resource sector play its role in the social and economic transformation, inclusive growth and the sustainable development of African economies. As of March 2025, Liberia had not yet ratified the statute or joined the AMDC (African Union 2021).

Nigeria has actively engaged in cross-border enforcement initiatives through ECOWAS frameworks, working with neighbouring countries to share intelligence and disrupt smuggling networks. Ghana has developed regional cooperation mechanisms, often in collaboration with Nigeria and other West African states that help harmonise regulations and coordinate enforcement actions. These initiatives have improved the tracking of mineral exports and reduced trade mispricing, serving as effective models for Liberia (UNCTAD 2020: 171-176).

Strengthening ties with international partners is also a key prerogative, including major transit hubs such as Belgium, India, the UAE, US, Israel, Switzerland and China (see Table 1) (OEC 2023). These partnerships can enhance due diligence in the global supply chain and ensure that illicitly sourced minerals are not integrated into the legal market (Spatz 2024).

Community engagement

Local communities are often the most affected by IFFs and corruption in the mining sector. Engaging these communities can empower them to hold local authorities and mining companies accountable. For example, in Siera Leone, local monitoring committees have been established to oversee mining activities and ensure that revenues are used for local development. These committees can act as watchdogs and report irregularities to higher authorities (Hunter and Smith 2017: 19-20).

Investing in training programmes for local communities to enhance their understanding of mining contracts, legal rights and environmental safeguards can, in the long term, lead to significant beneficial impacts. In the DRC, various initiatives supported by international organisations focus on training communities on mining contracts, legal rights and environmental safeguards. The Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) runs a project on long-term economic development in mining, which provides trainings in public institutions to help manage taxes in a transparent manner and offers trainings for alternative opportunities for employees in the extractive industries (GIZ 2023). There is some evidence that educated communities are better equipped to demand accountability from both the state and mining companies (OECD 2020: 23; Hunter and Smith 2017: 34). However, as mentioned above, formalisation efforts should also be co-led with local, affected communities.

Another way of engaging the community is to ensure that a fair share of mining revenues is reinvested into local infrastructure and social causes. Transparent benefit-sharing mechanisms can reduce local grievances and deter corrupt practices at the community level (Global Witness 2018). Ghana’s Mining Community Development Scheme offers an example how to ensure that a percentage of mineral royalties is reinvested into local communities. Community-based monitoring groups oversee these funds, ensuring they are used for infrastructure, education and healthcare (MCG 2021).

- Illicit financial flows (IFFs) are financial flows that are illicit in origin, transfer or use, that reflect an exchange of value and that cross country borders (UNCTAD n.d.).

- Secrecy jurisdictions refer to locations characterised by laws and structures that promote secrecy, enabling individuals to hide their financial assets from tax authorities and other claimants, and enable criminals to launder wealth accumulated through illicit means (GFI n.d.).

- It should be noted in recent years that the UAE has stepped up enforcement efforts, although these remain limited. For example, in 2023 authorities suspended the licence of 32 gold traders for AML issues, but only for a period of three months (OCCRP 2023).

- These include but are not limited to the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA) and the Responsible Minerals Initiative.