Query

Please provide a summary of best practices on mainstreaming anti-corruption safeguards into donor-supported capacity building of law enforcement in partner countries.

Introduction

Capacity building of law enforcement

Many donors regard it as paramount to invest in the capacities of law enforcement in low and middle-income countries (Zaum et al. 2012). Well-equipped and trained law enforcement agencies can better contain the local occurrence of crime and improve security, thus providing the stability needed to allow wider development interventions to flourish. Additionally, curbing sophisticated, transnational forms of crime that have wider geographical impacts requires highly competent law enforcement agencies in both donor and aid-recipient countries. Interventions intended to strengthen law enforcement in partner countries often, but not always, fall under the concept of ‘security sector reform’ (SSR).c04587394b5c

Capacity building is seen as a practical means of strengthening institutional quality and, in some donor-funded development programmes, most of the budget is dedicated towards it (Tostensen 2018: 21). While the term ‘capacity building’ is most often associated with training and forms of technical instruction, donors may also understand it as encompassing activities such as the provision of tools and equipment and the deployment or seconding of experts (GAC 2023).1fe4f2bf7e5a These activities can support law enforcement in the fulfilment of their core functions and their ability to respond to emerging crimes and new criminal methods.

The links between corruption and capacity building for law enforcement are perhaps most apparent where police and other actors are specifically trained and supported to investigate suspected acts of corruption as well as where capacity building focuses on reducing organisational corruption within law enforcement agencies (LEAs) (Zaum et al. 2012). Indeed, the reported success of countries such as Georgia and Singapore in curbing police corruption has been partially attributed to reforms involving training programmes targeting LEAs focusing on integrity and anti-corruption (Lee-Jones 2018; Bak 2021).

However, capacity building can be geared towards other aims; for example, Global Affairs Canada implements an anti-crime capacity building programme supporting LEAs in partner countries to address corruption and other crimes such as cybercrime, illicit drugs, and human trafficking and migrant smuggling (GAC 2023).

Even though they do not establish the reduction of levels of corruption as a primary objective, either within LEAs or more widely in society, integrating anti-corruption safeguards into such programmes is important. There is always a possibility that corruption and financial irregularities can arise in the planning and implementation of capacity building activities, obstructing the achievement of goals and leading to a waste of donor funds (Jenkins 2016).

Mainstreaming anti-corruption into development programming

Donors have long recognised the need to ‘mainstream anti-corruption as an integral dimension of the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of programmes and policies’ (Chêne 2010a). However, there are different understandings of what mainstreaming exactly entails. For example, under a typology developed by USAID (see Figure 1), ‘sectoral or cross-sectoral anti-corruption integrated programming’ could entail enhancing expenditure controls and anti-corruption safeguards across the health, education and agriculture sectors. Such programming expressly aims to address corruption in a given sector and have a lasting impact beyond the immediate project.

Figure 1: Types of Anti-Corruption in USAID Programming

|

Type |

Description |

Example |

|

Anti-corruption programming |

Has a project purpose with an explicit focus on improving partner country systems and capacity to prevent, detect, investigate and disrupt corruption. |

A project aiming to support national level anti-corruption agencies to better identify and investigate cases of corruption (e.g. Indonesia CEGAH). |

|

Sectoral or cross-sectoral anti-corruption integrated programming |

Has a project purpose that focuses on country system strengthening for a sector or set of sectors and expressly aims to address corruption and/or advance integrity. |

A cross-sectoral programme focused on enhancing expenditure controls and anti-corruption safeguards across the health, education and agriculture sectors, and addresses other sector finance issues (e.g., Uganda GAPP). |

|

Sectoral programming with anti-corruption elements |

Has a project purpose that focuses primarily on improving a set of sectoral outcomes, but which includes activities that address related corruption risks. |

A project focused on improving maternal and child health outcomes, in part by working to reduce absenteeism and theft of resources in health clinics (e.g., Pakistan Maternal and Child Health Program). |

|

Anti-corruption safeguards and controls |

Required elements of USAID’s regulations, policies and procedures that enable more effective detection, prevention and response to corruption risks in USAID funded assistance activities. |

Practices on a project seeking to streamline controls or document and report concerns related to commodity loss, sanction violations, waste, fraud, and abuse, and sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) (e.g. USAID's Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance Documenting, Reporting, and Responding to Program Irregularities). |

Source: USAID 2022b: 13-14

In contrast, programming to integrate ‘anti-corruption safeguards and controls’ focuses on reducing what is often referred to as ‘fiduciary risk’. The Independent Commission for Aid Impact (2016: 9) defines fiduciary risk as ‘the risk that funds entrusted to third parties to deliver aid are not used for their intended purposes and/or cannot be properly accounted for’.

Indeed, while recognising that donor-funded development programmes in the law enforcement sector can prioritise the reduction of corruption as an explicit goal, this Helpdesk Answer primarily focuses on fiduciary risks. Nevertheless, as discussed below, such categories may be mutually serving, and programming integrating different approaches may offer advantages in terms of effectiveness.

As for mainstreaming anti-corruption safeguards, the most common approach taken by donors is the adoption of strategies, protocols and standards guiding their overall development programming, rather than establishing bespoke approaches for specific subsectors. For example, the Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development of Germany (BMZ) makes it mandatory for BMZ employees and staff from implementing organisations to apply a quality criterion related to the prevention of corruption when assessing and designing programming (BMZ 2022). The approach further imposes anti-corruption and integrity commitments on implementing organisations, who ‘must incorporate anti-corruption and integrity into all stages of the planning, design and implementation of programmes and modules and use the reporting process to set out measures and any action that is required’ (BMZ 2022:21-22).

Similarly, the Swiss Development Cooperation (SDC 2020) has committed to mainstreaming anti-corruption into its programming decisions across all thematic domains with the goal of ‘ensur[ing] that projects and programmes, even if they are not directly focusing on corruption, are designed so that they improve the conditions in each specific context to prevent and reduce corruption’. Furthermore, in 2023, the European Council (2023) highlighted the importance of incorporating a strong anti-corruption perspective in all development efforts, such as in health, education and the efforts to curb climate change.

A 2022 review of the recommendation of the OECD Council for Development Co-operation Actors on Managing the Risk of Corruption concluded that all 40 OECD members as well as 6 non-members had largely adhered to the different elements in the recommendation, suggesting a strong consensus among donors on the importance of mainstreaming anti-corruption.1c2c761cf529

This is not surprising given that donors clearly have an interest in ensuring the proper use of the funds they have allocated to a stated development objective and thus reducing fiduciary risk; it may also be prompted by taxpayers’ concerns that development aid is being squandered as a result of unchecked corruption (Mason 2021: 1). Furthermore, donors may wish to ensure their activities do not contribute to corruption levels in a certain sector in line with a ‘do no harm approach’ (Boehm 2014: 1), not least because such allegations can carry reputational risks which may hinder future programming in a specific target country.

Modern development programming typically operates through complex delivery chains involving donor agencies (including headquarters and country offices), plus partner implementing agencies (for example, multilateral or international civil society organisations and national institutions), as well as multiple sub-grantees or sub-contractors, and, ultimately, the target beneficiaries. Any of these actors may be implicated in corrupt practices during the project life cycle; for illustrative purposes, Figure 2 shows a list of the partners responsible for financial irregularities in Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD)’s programming between 2010 and 2019.

Figure 2: Categorisation of financial irregularity by partners in NORAD programming 2010-2019

| Category | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | Total | % |

| Norwegian NGO | 14 | 14 | 27 | 30 | 33 | 35 | 40 | 28 | 51 | 44 | 316 | 65% |

| International NGO | 1 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 40 | 8% |

| Local NGO | 1 | 1 | 11 | 6 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 47 | 10% |

| Embassy | 0 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 22 | 5% |

| Multilateral | 1 | 0 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 24 | 5% |

| Bilateral | 3 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 39 | 8% |

| Total | 17 | 22 | 59 | 53 | 57 | 55 | 57 | 44 | 62 | 59 | 485 |

Source: NORAD 2020

Corruption risks associated with LEA capacity building programmes

This section surveys the evidence on how corruption can frustrate efforts to improve the effectiveness and increase the capacities of law enforcement agencies.

In 2016, the LET4CAP (Law Enforcement Training for Capacity Building) project was launched. Funded by the Internal Security Fund of the European Union, it brought law enforcement officers from various EU member states’ agencies to deliver training to their counterparts in third countries; 75 participating law enforcement officers responded to a project survey identifying corruption as one of the key operational and systemic challenges they faced (Creta 2019).

Capacity building is vulnerable to many of the corruption risks generally associated with donor-supported programming, but some more specific risks are described below.

- Procurement of training related services such as contracting of trainers, development of curricula, tendering for venues, accommodation, catering, etc. The main corruption risks associated are fraud, conflict of interest and patronage, especially where project staff intervene to unfairly award contracts to their compatriots (Jenkins 2016: 9).

- Human resource management, especially concerning nepotism and favouritism affecting appointments to positions and teams responsible for implementing the programmes (Klangefeldt 2024), payroll tampering (Jenkins 2016) and the selection of training beneficiaries. Jenkins (2016) describes how target institutions might nominate participants who are not the intended audience for the perceived career advancement associated with capacity building, which can make the intended transfer of knowledge redundant.

- The payment of per diems (also known as daily subsistence allowances – DSAs) to compensate participants in capacity building activities for travel and other expenses. While this can function as a way of securing participation by key staff, Tostensen (2018) explains that in some cases per diems can be viewed as a bonus payment and lead beneficiaries to abuse them by, for example, participating in more training programmes than they require or in areas irrelevant to their work. Søreide et al. (2016) found this can be especially the case for donor-financed programmes where per diem rates are higher; risks are further pronounced where there is a lack of coordination across donors, leading to duplicative training with repeat participants.

- Embezzlement of programme funds and assets (such as donated equipment or training material). This can occur through misappropriation or other means such as overbilling and the invention of ‘ghost partners’, non-existent contractors who are allocated funds (Jenkins 2016).

- Bribery, for example, of local public officials to obtain necessary permits or licences and accelerate visa processes for the capacity building exercises.

These risks may be more or less likely depending on the exact modalities of the intervention and the delivery chain used. The former UK development agency DFID (2015: 39) found that SSR capacity building interventions are often more successful where donors take a flexible approach and entrust national and local actors with the decision-making to foster a greater sense of ownership. For example, while training may be carried out by donor-country personnel or private firms, there may be a preference for hiring local specialists more familiar with the specific context (such as ability to instruct in the local language) and needs of the target country (DFID 2015: 12; 21). However, this approach requires donors to relinquish some control over the selection process for contractors hired to conduct or support capacity building activities.

There are other unique risk factors associated with law enforcement actors being the target beneficiaries of capacity building. In certain contexts, police and other law enforcement agents behave in a corrupt manner or abuse their power during the course of carrying out their duties. For example, this can include accepting bribes from citizens to overlook traffic violations or even collaborating with organised crime groups to facilitate their illicit activities (Lee-Jones 2018). Law enforcement actors may be more prone to engaging in other forms of corruption; for example, between 2018 to 2021, allegations relating to the abuse of position for sexual purposes accounted for 60% of all internal corruption investigations involving police in the UK (IOPC 2022).

Law enforcement bodies can be hierarchical in nature and corruption may be driven by the prospect of career advancement. For example, one study found allegations that 35 national police personnel nominated to take part in UN peacekeeping missions paid bribes to officials in their home countries to have their mission contracts extended (Transparency International Defence and Security 2016: 35). Another driver is the intra-organisational solidarity typically present in LEAs which may disincentivise officers from reporting their peers’ corrupt behaviour (Bak 2021).

Moreover, Ronceray and Segrejeff (2020) warn that in some cases law enforcement may weaponise anti-corruption and use it to repress political opposition, making it important that technical assistance to such agencies does not result in offering them ‘a varnish of legitimacy’. Furthermore, corrupt law enforcement actors can enjoy effective impunity for their crimes given that they may be the very same actors entrusted to enforce corruption laws (USAID 2019: 58). Lastly, the security sector usually attracts high allocations of public expenditure often in combination with confidentiality prescriptions, which can limit open competition for tenders and external auditing (Joly 2021; OSCE 2022: 244).

Furthermore, there is often a strong demand, especially under SSR programming, for law enforcement capacity building in conflict-affected and fragile countries. However, in such contexts, an environment of weak governance as well as socio-economic pressures can give rise to an increased risk of corruption (OECD 2022), making oversight and risk management more challenging to implement (Bak and Jenkins 2024). For example, when the former UK agency DFID scaled up its SSR programming in conflict-affected and fragile countries, it needed to rely more on local actors, including sub-grantees or sub-contractors, with whom it had limited contact and less oversight opportunities (Independent Commission for Aid Impact 2016: iii).

Taken together, and especially in conflict-affected and fragile contexts, these factors indicate that donors need to be wary of the possibility that they are entering an environment of weakened institutional controls. If the assistance is then designed without consideration for corruption risks, programme beneficiaries are also at risk of being implicated in subsequent scandals, which can entail significant reputational risks.

Afghanistan police force

Between the inauguration of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistanin2004 and the Taliban’s return to power in 2021, the US, the UK and other donors allocated substantial funding towards the capacity development of Afghanistan’s law enforcement agencies, with a view to countering insurgency and terrorism threats, as well as curbing opium cultivation and trafficking, among other issues. A large portion of this was channelled through a trust fund – Law and Order Trust Fund (LOFTA) – managed by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) to support the Afghanistan National Police (ANP) with training, equipment and salary payments.

Nevertheless, recurring reports were made about corrupt practices during implementation, including:

- the diversion of training funds for police officers’ personal gain

- the misappropriation of equipment, including weaponry

- the listing of non-existent personnel or ‘ghost officers’ on payrolls to extract salaries

- procurement fraud linked to the LOFTA

- government officials’ attempts to suppress reports about corruption

(Independent Commission for Aid Impact 2022; Bak 2019)

Such transgressions elicited responses from donors. In 2010, US police trainers reportedly highlighted how corruption was undermining its efforts to improve the capacity of the ANP (Perito and Kristoff 2010). In 2018, several donors withheld disbursements, leading to an estimated 30,000 Afghan police officers not receiving their salaries (Bak 2019).

At the same time, many donors continued to provide funding to the ANP, reportedly seeing it as a necessary trade-off to contain the growing influence of the Taliban and other insurgents (Independent Commission for Aid Impact 2022). Nevertheless, according to some commentators, corruption ultimately contributed to the poor preparedness of the ANP and other security actors to prevent the Taliban incursion in 2021 (SIGAR 2022).

Anti-corruption risk management and safeguards

This section describes some of the anti-corruption safeguards that can be integrated into donor-supported capacity building of law enforcement to reduce the risks of corruption. As exemplified by the 2016 recommendation from the OECD Council for Development Co-operation Actors on Managing the Risk of Corruption, there are many potential entry points. This section does not cover these exhaustively but rather focuses on those assessed by the author to be most relevant for the capacity building of law enforcement. Likewise, for illustrative purposes it draws examples from a selection of donor approaches.

Recommendation of the OECD Council for Development Co-operation Actors on Managing the Risk of Corruption

In 2016, the OECD adopted this recommendation to guide donors on how to ‘set up or revise their system to manage risks of and respond to actual instances of corrupt practices in development co-operation’ (OECD 2016).

It identifies ten key elements, the headings* for which are reproduced here:

- Code of conduct (or equivalent)

- Ethics or anti-corruption assistance/advisory services

- Training and awareness raising on anti-corruption

- High level of auditing and internal investigation

- Active and systematic assessment and management of corruption risks

- Measures to prevent and detect corruption enshrined in ODA contracts

- Reporting/whistleblowing mechanism

- Sanctioning regime

- Joint responses to corruption

- Take into consideration the risks posed by the environment of operation

A 2022 OECD report reviewed OECD members’ progress in implementing the recommendation (OECD 2022). It flagged common strengths such as the use of corruption assessments, financial audits, codes of conduct, training and anti-corruption clauses in contracts and agreements. However, it noted some common shortcomings such as donor countries failing to adequately support partners to manage corruption risks during programme implementation. The report also highlighted the importance of going beyond managing fiduciary risks ‘to take a more comprehensive approach to corruption risk management, including by appreciating the influence of reputational, institutional and contextual risks on corruption risk management practices, and the importance of ‘doing no harm by not contributing to corruption dynamics’.

* The full recommendation contains sub-provisions giving further guidance on implementation measures.

Risk assessment

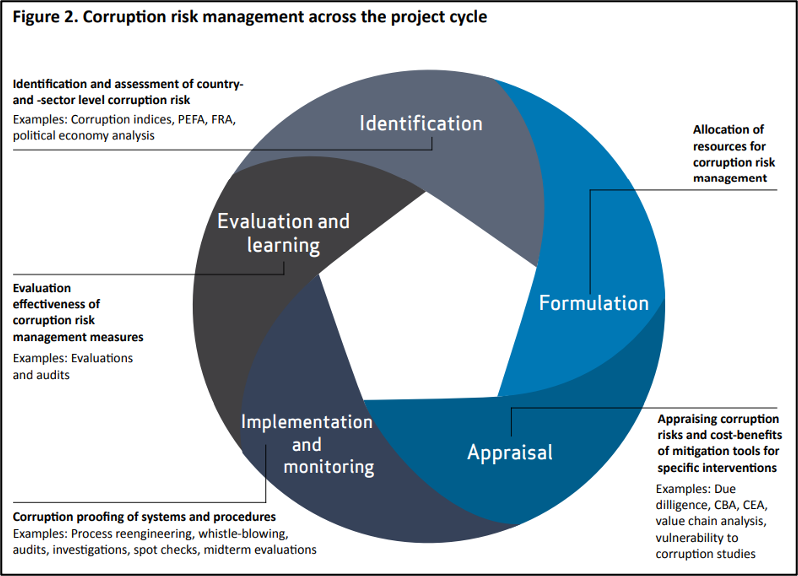

To protect their funds from corrupt misuse, most donors have established risk management protocols across the entire cycle of a project or programme. This reflects a maturing understanding that corruption can occur at any stage of a development assistance initiative, from policymaking through to impact evaluation, and is not solely attributable to external partners. An evaluation by NORAD of anti-corruption as part of its development efforts between 2010 and 2019 found that suspected financial irregularities could be attributed to weaknesses occurring at all stages of the project cycle (NORAD 2020: 5).

Johnsøn (2015) provides a model which breaks down the various elements of a risk management approach across a simplified project cycle (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Johnsøn’s model of corrupt risk management across the project cycle

Source: Johnsøn 2015: 17

The first step is to carry out a risk assessment (often called a corruption risk assessment – CRA – or fiduciary risk assessment – FRA), which aims to categorise and measure different risks. These risk assessments are typically conducted before a project has been approved. As part of this exercise, donors identify tolerable levels of risk (the risk appetite). Some risks may be considered unacceptable, in which case the project usually is not approved, or its design is altered significantly, while others (residual risks) may be accepted if the activity is deemed significant enough and certain safeguards are established to reduce the identified vulnerabilities (Hart 2016).

The level of risk is normally determined by calculating the likelihood and impact measures against estimates of corruption levels in relevant sectors and institutions. These estimates may also include key characteristics of the proposed project such as: size of the budget, financial management capabilities of partners as well as delivery mechanisms. Even more importantly, this evaluation encapsulates the impact that risks could have on the project’s overall development outcomes, should they materialise (Johnsøn 2015: 17).

Donors use different modalities for gathering data on risks, including deployment of missions or through desk research. A risk assessment can be carried out at country level – for example, a political economy approach (Hart 2016; FCDO 2023b6f0f50a4681) – but many donors (BMZ 2022:16; AUSAID 2008) favour sector specific analyses as they are more attuned to the most damaging forms of corruption in the targeted sector or institution. Sectoral assessments may also be better placed to identify the regulatory, socio-economic and institutional drivers of corrupt behaviour (Hart 2019: 10).

For interventions supporting the capacity building of law enforcement then, risk assessments can be an important tool for donors to determine how the existing governance landscape (such as the level of police corruption) could affect target beneficiaries as well as implementing partners and sub-contractors within a certain sector and/or country.

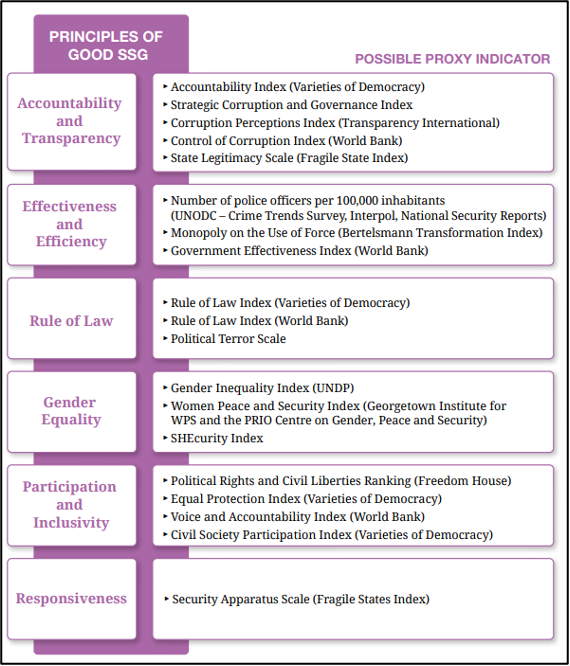

Joly (2021) notes that while many entities have carried out SSR assessments of countries and their law enforcement agencies, these often do not consider corruption. However, other proxy indicators can help inform donors’ sectoral assessments for capacity building for law enforcement purposes (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: The OSCE’s list of principles of good security sector governance (SSG) and possible indices for measuring them.

Source: OSCE 2022: 196

Law enforcement agencies can also integrate risk assessment approaches for their own internal purposes; the OSCE Mission of Serbia, for instance, supported the Ministry of Interior to develop guidelines for corruption risk analysis, which have now been included in the main training curricula for different branches of the police (OSCE 2022: 242). Example 1 in the annex demonstrates the application of a risk assessment for capacity building programme for law enforcement.

Risk mitigation

If, following a risk assessment, the decision is made to proceed with a project proposal, mitigation measures should be built into the project plans, and ongoing monitoring of residual risks should be carried out by, for example, drafting a risk matrix which is continually updated (Jenkins 2016: 9). However, the OECD (2022) found that it is often the case that, though donors’ initial risk assessments are of high quality, follow-up risk monitoring tends to be lacking (OECD 2022: 37); similarly, Hart (2016) found that the ongoing monitoring of risks can become deprioritised during implementation.

USAID’s Public Financial Management Risk Assessment Framework (PFMRAF) manual outlines a two stage process, as part of which a rapid appraisal and then a more comprehensive risk assessment are undertaken to determine fiduciary risk levels, following which approved projects must incorporate a risk mitigation plan (USAID 2014).

Figure 5: USAID’ Illustrative example of a Risk Mitigation Plan

|

Identified risk |

Potential adverse effect of risk |

Recommendation from risk assessment |

Impact |

Prob. |

Risk rating |

Mitigation measure |

Responsible parties |

USAID follow-up, monitoring |

|

There are no fixed asset records nor are there efforts to reconcile a physical count of fixed assets to fixed asset records |

Lack of proper accounting and verification of fixed assets provides inadequate control over fixed assets. Assets can be easily removed from the district premises without management’s knowledge. |

Entity prepares a fixed asset registry that contains detailed fixed asset information. Conduct annual inventory of fixed assets and reconcile to the fixed asset registry. |

2 |

2 |

Med. |

1. Prepare fixed asset register with data on all fixed assets 2. Establish procedures for annual inventory of fixed assets and reconcile to register |

Financial analyst; technical officer |

Semi-annually |

Source: USAID 2014: 35

Agreed mitigation measures should be reflected in project documentation (Hart 2019), such as implementation plans and logframes, including indicators that enable project staff to track the effectiveness of these measures over time (see the annex for examples of how anti-corruption safeguards have been integrated in the project documentation of capacity building interventions for law enforcement).

Furthermore, it is important that the process of establishing risk mitigation measures is aligned with budget planning to ensure that sufficient financial resources are allocated to each measure (Olaf Palme Center 2012: 11).

An assessment by the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (2016: 21) into DFID’s anti-corruption mainstreaming found that financial staff in partner organisations were generally unaware of programme plans until late in their development. The recommendations suggested that partner staff should be engaged early in the design process to ensure they are familiar with all processes, which would also strengthen a greater sense of ownership.

At a best practice exchange among donors, the point was made that project stakeholders should agree as early as possible on common expectations related to the inclusion of anti-corruption rules, processes and standard operating procedures (Klangefeldt 2024). In terms of capacity building for law enforcement, this could include:

- The inclusion of codes of conduct setting out what is expected of project implementing staff and beneficiaries (Joly 2021). It is important to have conceptual clarity on what kind of behaviour amounts to corruption.062a2a959359 For example, Denmark in its anti-corruption policy clearly defines terms such as conflict of interest and bribery (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark 2018); the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA 2021) explicitly notes that other offences such as favouritism in recruitment and certain types of sexual exploitation could be considered as forms of corruption.

- Developing clear criteria on the intended target beneficiaries for training and other opportunities, which can be used to gauge law enforcement agencies’ nominations of participants and their relevance for the capacity building activity (Jenkins 2016). Similarly, if an assessment identifies a risk of per diem abuse, clear policies can be included that set out standardised per diem rates and under which conditions participants are eligible to receive them.b41d6c1ea631

- If there is a risk of embezzlement, robust financial management processes (described in more detail below) can ensure a greater oversight of funds. For equipment provided, supervisory plans and ownership agreements can be developed (Olaf Palme Center 2012: 11).

- Incorporating citizen participation and oversight into programming can foster better relations between law enforcement and the citizens they serve. In this way, citizens may be able to provide more independent assessments in contrast to potentially biased law enforcement actors. For example, civil society organisations can be involved in operating whistleblower mechanism, among other measures (UNDP 2008).

Other risk mitigation measures take the form of ongoing practices and activities undertaken throughout project implementation, such as training, financial management and internal controls, which the remainder of this section is dedicated to describing in more detail.

Training

Project personnel need to be able to interpret and implement guidelines and policies for them to have any effect (Klangefeldt 2024). This makes training an important means of ensuring that risk mitigation policies are understood and adhered to. For example, Bak (2021) describes how in-house training helps to make codes of conduct for police more effective.

Various actors across the delivery chain may require training. As Jenkins (2016) explains, ‘non-specialist project staff tasked with programme planning and implementation are often ill-equipped and underprepared to identify and address the corruption risks they face’. Many donors note that, in addition to partner staff, their own agencies’ staff also require tailored training to ensure consistent and specialist knowledge on the mainstreaming of anti-corruption across different areas of development (BMZ 2022:5; USAID 2022a: 35-36)

USAID describes how this should be reflected at a strategic level and integrated into planning documents (USAID 2022a: 35-36), providing a sample indicator (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: USAID sample indicator for anti-corruption training

|

Indicator |

Definition |

Relevance |

Data collection methods |

|

Number of US Government- supported national human rights commissions and other independent state institutions charged by law with protecting and promoting human rights that actively pursued allegations of human rights abuses during the year (FA DR.6.1-1) (output) |

To be counted, the commission or institution: • must have the authority to investigate and adjudicate human rights violations • must be funded by the government • must be actively investigating cases. Actively means that paid staff are interviewing witnesses, documenting evidence, writing reports, etc. Information should be reported by USG fiscal year. |

This indicator highlights acceptance by the government of the private right to file complaints in domestic institutions against governmental abuses and allow and pay for full investigations. This acceptance shows a willingness for government accountability and transparency to the public on human rights issues. This accountability can also strengthen the legitimacy of the government. An increase in the number of USG supported human rights commissions actively pursuing allegations of human rights abuses suggest the probability that USG support allows for more government accountability and transparency, which will decrease human rights violations. A decrease in the number of USG supported human rights commissions actively pursuing allegations of human rights abuses suggests that the lack of USG support could allow for less government accountability and transparency, which could result in more human rights abuses. |

Annual review of implementing partners’ project/activity documents, official government journals, news media, and on-site observation by USG officials. |

Source: USAID 2019: 60

This can take the form of general ethics training on, for example, operationalising codes of conduct applicable to projects and explaining key concepts such as conflict of interest, as well as in the form of more specialised training catering to different staff functions, such as programme management and procurement (OECD 2016). For capacity building interventions, training could prioritise relevant activities such as administering per diem payments.

Training can also be scenario based and country specific to make sure they reflect the likely risks more accurately (OECD 2022: 24). However, in a survey carried out as part of a review of the 2016 OECD recommendation, 90% of responding states said that training was a core mainstreaming measure, but less than half said they tailored their training to ‘different staff categories, contexts and/or levels of risk’ (OECD 2022: 22).

In its 2022 review of the recommendation, the OECD (2022: 24) highlighted the importance of informal forums such as mentoring hubs, having ongoing peer-to-peer support rather than one-time training, as well as ensuring that training covers all staff categories. DFID used a combination of formal and informal processes to improve fiduciary risk management, including training sessions, on-boarding processes, online forums, staff secondments, staff rotation and exchanges between country offices (Independent Commission for Aid Impact 2016: 36).

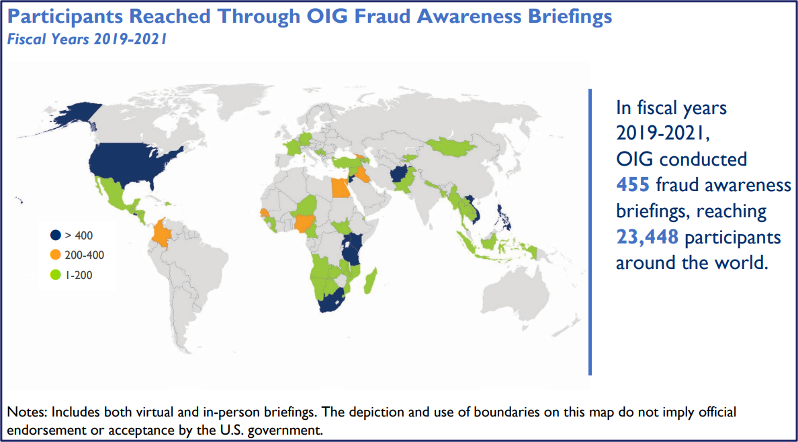

Donors may make use of online training methods to reach more staff (OECD 2022: 24). For example, between 2019 and 2021, USAID’s Office of Inspector General reached 23,488 participants with their fraud awareness briefings(see Figure 7).

Figure 7: USAID Office of Inspector General’s data on fraud awareness briefings carried out for USAID partners between 2019 and 2021

Source: USAID 2022c

Several donors have highlighted the online courses on the U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre platform as important resources for their own and partner staff (Klangefeldt 2024). Examples 2 and 3 in the annex illustrate how partner trainings have been incorporated into capacity building programmes for law enforcement.

Financial management

Where implementing partners adhere to robust financial management standards, this can act as a significant internal control against risks such as embezzlement and conflict of interest in procurement, among others. Development agencies can verify whether their partners employ qualified accountants able to diligently fulfil bookkeeping, financial reconciliation and recordkeeping requirements (Olaf Palme Center 2012: 17). Specifically, for in-person workshops, donors can require beneficiaries to sign daily participation lists and then verify them to counter risks of per diem abuse. Development agency staff can conduct spot checks on training sessions to compare the list of participants who signed up with actual attendees (Jenkins 2016).

Furthermore, there should be clear procedures for how financial decisions are made. This includes conducting due diligence on bidders in procurement processes to provide resources such as training personnel, venues and catering for capacity building activities. This can entail assessing whether bidders have already been convicted of relevant offences (BMZ 2022:25). Although, the OECD (2022: 29) notes, this is dependent on the existence of comprehensive registers of prior convictions or using other reputation screening tools (Autran and Musso 2022) to assess their track record in supplying quality goods and services as well as potential conflict of interest concerns.

The BMZ (2022:26) advises that rather than imposing an unfamiliar financial management system on implementing partners, development agencies should work, where possible, with the partner organisation’s existing accounting system and financial controls. Where necessary, a secondary objective of a development assistance project can be used to improve the quality of implementing partners’ financial management systems. Nevertheless, while donors often delegate project implementation duties to partners, they can still ensure external monitoring checks are in place. This can be done, for example, through scheduling monitoring missions or audits in project documentation (SIDA 2021: 9) or making financial disbursements conditional upon results.

If donors do not have a presence in or are unable to travel to the target country, they typically contract a third-party monitoring or auditing firm (Independent Commission for Aid Impact 2016: iii). Additionally, some donors have started using innovative measures to monitor partners. When monitoring SSR programming in Somalia, DFID relied on remote techniques, such as vehicle trackers, satellite imaging and call centres to ask beneficiaries whether they had received their full per diem (Independent Commission for Aid Impact 2016: 31). KfW – the German development bank – developed a blockchain-enabled technological tool called TruBudget (Trusted Budget Expenditure Regime), which allows an overview of the real-time use of funds by partners and enables remote approval steps for donors (BMZ 2022:14-15). Aarvik (2019) describes how donors are starting to make forays into using artificial intelligence tools to implement financial management processes instead of relying on partners who may be susceptible to engaging in corrupt practices.

Examples 1 and 2 in the annex contain a set of financial management measures deployed in capacity building programmes for law enforcement.

Detection and sanctions

While mitigation measures can reduce corruption risks to a degree, donors must nevertheless establish measures to detect corruption and, where a suspicion is substantiated, offenders should be sanctioned.

Donors should ensure all implementation staff, partners and beneficiaries involved in programmes have access to anonymous reporting, whistleblower mechanisms, with well-established, clear instructions on how complaints are handled and escalated. Many donors also impose an obligation on staff and partners to report cases where they have a reasonable suspicion of corruption (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark 2018; BMZ 2022:18).

Donors may make use of different avenues to investigate violations, depending on which actors are implicated. For example, the BMZ (2022: 21-22) stipulates that implementing partners are normally responsible for investigating any allegations of corruption arising during the execution of the project, such as by sub-contractors. However, in cases where implementing partners may be implicated, there may be a need for the involvement of the donor or an external investigator. For, example, USAID operates an Office of the Inspector General, which consists of around 40 federal law enforcement officers operating globally who can undertake criminal and civil investigations into suspected corruption in foreign aid programmes (USAID 2022c).

In a substantiated case of corruption, donors may consider a different range of actions, such as the imposition of more stringent mitigation measures like enhanced monitoring but may also decide to suspend programmes and attempt recovery of funds (BMZ 2022: 18). Most donors include so-called anti-corruption clauses in contractual arrangements stipulating the consequences if partners are found complicit of corruption during the implementation of the project, including suspension of funding and mandatory investigation processes (Chêne 2010b; OECD 2022: 29).

As an illustrative example, due to allegations that Nigerian police has mismanaged national budget and donor funds, Human Rights Watch (2010) recommended that Nigeria’s foreign partners impose visa bans on the perpetrators, make any future financial assistance to the Nigeria Police Force conditional ‘on measurable progress on holding accountable police officers implicated in corruption and other serious abuses’ and require police officers who participate in training courses to make asset declarations.

Challenges

This section describes some of the challenges that donors encounter in mainstreaming anti-corruption safeguards, which not only increase the likelihood and impact of corrupt behaviour but also have other repercussions, such as inhibiting the achievement of programme goals.

Adaptability

On one hand, donors may understandably be predisposed to looking for common and consistent anti-corruption approaches and templates, scalable to the different kinds of interventions they support. On the other hand, such interventions typically occur in a wide range of contexts, posing different corruption risks, demanding a more nuanced approach (Ronceray and Sergejeff 2020) by, for example, using adaptable tools that cater to different risk levels.

This is especially important for capacity building interventions in conflict-affected and fragile states. For this reason, DFID justified a transition from a‘rules-based to a principles-based programme management system’. This entailed decentralising fiduciary risk management so that local staff could take management decisions in a flexible way while adhering to overarching principles, which DFID argued was an advantage in conflict-affected and fragile states where risks can take unique forms and change rapidly (Independent Commission for Aid Impact 2016: 16). Similarly, in its 2022 anti-corruption strategy, USAID committed to undertaking more ‘meaningful analysis of corruption risk in countries affected by conflict and violence’ (USAID 2022a: 35-36). Bak and Jenkins (2024) highlight how involving local experts in AML/CFT (anti-money laundering and combatting the financing of terrorism) capacity development projects in conflict-affected and fragile states can make for more effective and context-responsive interventions and foster more local ownership.

Trade-offs

Integrating anti-corruption safeguards into programming can entail costs, both financial and otherwise. Training, monitoring and other risk mitigation measures require donors to allocate sufficient financial resources; otherwise, there is a risk the safeguards amount to no more than ‘superficial technical fixes’ (Mason 2021: 28). At the same time, this entails donors often spending significant levels of funds on measures that are not the primary objective of the programme.

Furthermore, donor and partner staff may view the requirements as burdensome, especially if not adequately accounted for in planning. Indeed, programme staff often report feeling a lack of incentives for mainstreaming anti-corruption in their area of work (Mason 2021: 27). Some development agencies are reportedly characterised by a siloed approach in which different departments do not collaborate efficiently with each other and technical expertise remains unshared (Chêne 2010a). A mainstreaming approach may encounter internal resistance if adequate incentives and resources are not provided. Boehm (2014: 3) found that staff often prefer instruments such as anti-corruption training and policy documents rather than compulsory indicators which may be perceived as inflexible.

Anti-corruption safeguards can carry wider costs; ironically this may be especially true where they are effective in detecting instances of corrupt behaviour as this may result in the withdrawal of funds or the suspension of the development programme (NORAD 2020: 23).

This issue may be especially acute where a donor adopts a policy of zero-tolerance on corruption (see, for example, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark 2018). This hardliner approach may require donors to accord more resources to developing the anti-corruption capacities partners so they can accordingly reduce risks to “zero”.

NORAD (2020: 22) notes its adoption of a zero-tolerance approach was criticised by criticised by civil society organisations from Norway on the grounds that it lacked proportionality and sanctions were rarely differentiated according to the severity of the irregularity. In an evaluation of its own anti-corruption approach, NORAD (2020:6) found that, in deciding a course of action in response to instances of corruption, there was an excessive focus on punitive measures that did not support the anti-corruption capacities of partners in the Global South. Similarly, Strand (2020) adds that the strict consequences associated with a zero-tolerance approach may disincentivise whistleblowing and make corruption harder to detect.

This points to a need for donors to consider trade-offs when integrating anti-corruption safeguards into capacity building interventions. In this vein, the (OECD 2022:33) recommends that donors should carefully balance the need to minimise the risk of corruption compromising programme objectives and syphoning off donor funds against the potential developmental impact of the programme.

Integrated programming

As mentioned earlier, many donors and commentators argue that ‘mainstreaming anti-corruption’ must go beyond managing fiduciary risks to encompass broader, cross-cutting development goals, be that in SSR or other sectors (Transparency International Defence and Security 2023a).

This approach requires looking beyond the immediate environs of a project or programme to plan interventions that address underlying causes and risk factors. Johnsøn and Taxell (2015) found that the EU’s approach to mainstreaming anti-corruption into its development programming led to a ‘tendency to prioritise [its] own fiduciary risks at the expense of building up good national systems for corruption control’ and recommended more integrated programming focusing on strengthening national oversight institutions, such as supreme audit institutions.

Likewise, USAID (2022a: 37-38) in its anti-corruption strategy argues that in some contexts strengthening local oversight bodies would be the most effective way of safeguarding its project funds. Similarly, AUSAID (2008) proposed that donors should look beyond their own interventions towards coordinating and collaborating with each other to foster environments of greater accountability in target countries.

Annex 1: examples of anti-corruption safeguards in law enforcement capacity building projects

This annex gives examples of how ongoing and past donor-supported projects and programmes, with a focus on building the capacities of law enforcement agencies, have integrated anti-corruption safeguards. Given the large number of projects in this field sponsored by numerous donors, this list should be viewed as non-exhaustive; rather, these projects were selected to illustrate a range of delivery modalities. Furthermore, while relevant excerpts from project documentation are highlighted, they may not reflect the entirety of the specific intervention’s anti-corruption safeguards.

Example 1: Mekong-Australia Program on Transnational Crime (MAP-TNC)

MAP-TNC is an ongoing programme between 2021 and 2029 funded by the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) to strengthen the capacity of law enforcement agencies in Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam to ‘counter transnational crime and strengthen border security’, with a focus on drug trafficking, child sexual exploitation and financial crimes.

Prior to the project’s inception, an assessment was carried out, which concluded that the risk of corruption associated with implementation was small. Nevertheless, the project documented the integration of the following anti-corruption safeguards (Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade 2021). ‘The MC [Managing Contractor]60ed3a964d61 will put in place systems and processes that guard against fraud, nepotism and corruption, including':

- transparent processes for selection of local service providers and TA [Technical Assistance] personnel

- clear financial operating procedures that promote and take a zero-tolerance position on fraud

- compliance with the DFAT financial management, fraud control and accountability requirements

- an annual independent financial audit of the MC’s financial and programme management systems and of the programme’s annual financial report

- access to the financial management information and expenditure summaries at any time to nominated DFAT staff through a password-protected part of a web-based information management portal

- reflection of changes in anti-corruption profiles associated with the programme in the risk matrix’

Furthermore, the project document stipulates that the DFAT may require the managing contractor to conduct fiduciary risk assessments of law enforcement agencies for which no current FRA exists, as well as of private sector or non-governmental organisations involved with implementing the programme.

Example 2: Capacity Development Project on Anti-Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism in West Africa Transition States (CD4AML/CFT)

CD4AML/CFT is a project funded through a loan from the African Development Bank (AfDB) to the Intergovernmental Action Group against Money Laundering in West Africa (GIABA) to support the development of the capacities of agencies working against money laundering and terrorist financing.51eafbddee3c

An AfDB project evaluation mission assessed GIABA's overall fiduciary risk level as moderate (see Figure 8).

Figure 8: Fiduciary risk analysis table of CD4AML/CFT

|

Type of risk |

Notation |

Mitigation measures |

Deadline |

Conditionalities |

|

Inherent risk |

||||

|

Country Weaknesses in the public financial management system that may have an adverse impact on the project's financial management environment |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Executing agency Activity overload due to the volume of assignments and the large number of projects to be conducted at the same time |

Moderated |

Establishment of a dedicated PIU for the project |

Before negotiations |

No |

|

Project Lack of knowledge of the rules and procedures for managing bank-financed projects |

Moderated |

Training of the PIU on the rules and procedures for disbursement and financial management Designated a dedicated accountant for the project |

Launch |

No |

|

Non-controlled risk |

||||

|

Budget Absence of annual plan or default of its submission to the bank for no objection |

Moderated |

Specify the budgetary policy in the manual of procedures and submit to the bank each year the annual work plan and budget approved by the Steering Committee in due time |

Permanent action |

No |

|

Accounting Lack of private commitment accounting skills in an PFM environment |

Moderated |

Involvement of experienced accounting staff Training of the accountants on the accounting principles recommended by the bank |

Permanent action Launching mission |

No |

|

Internal control and internal audit Inadequate safeguards and controls that may lead to misuse of funds and jeopardise the successful implementation of the project

|

Moderated |

Updating the procedures manually to take into account the specificities of the project Integration of the project's financial operations into the internal audit programme of activities |

No later than three months after entry into force Permanent action |

No |

|

Financial flows Delay in the payment of company invoices or consultants' services |

Moderated |

Preparation of disbursement projections and close monitoring of disbursement requests |

Permanent action |

No |

|

Financial reports Production difficulties and delays in the transmission of financial reports |

Moderated |

Agreement on the format and frequency of financial reporting during the negotiations Ongoing support to the project from the bank's fiduciary teams in Senegal |

Project launch |

No |

|

External audit Delay in transmission of audit reports on accounts and internal control Weak capacity of external audit firms |

Moderated |

Agreement on the terms of reference for the project audits. Selection of only those audit firms judged to be performing well by the joint bank/World Bank evaluations |

Project launching Permanent action |

No |

Source: reproduced from African Development Bank 2022

This led to the development of a financial management action plan outlining several steps to manage the identified fiduciary risks in the project (see Figure 9).

Figure 9: Financial Management Action Plan of CD4AML/CFT

|

Domains |

Actions to be conducted |

Deadline |

Responsible |

|

Internal audit |

Adaptation of the current procedures’ manual to the specificities of the project and submission to the bank for validation |

No later than 3 months after the project comes into force |

Project implementation unit (PIU) |

|

External audit |

Recruitment of an external auditor |

No later than 6 months after the project comes into force |

PIU |

|

Accounting |

Acquisition of an accounting software for general, budgetary and analytical accounting |

No later than 3 months after the project comes into force |

PIU |

|

Flows of funds |

Opening of the special account and the sub-account |

After the project comes into force |

PIU |

|

Budget |

Submission of the approved annual work programme and budget (PTBA) to the bank before the beginning of each year |

Every year |

PIU |

Source: African Development Bank 2022

The project document envisions the establishment of a project implementation unit (PIU) within GIABA which holds fiduciary responsibility; the letter of agreement contains provisions that make the disbursement of funds conditional upon submission of evidence that qualified persons were hired to be part of the PIU. It was also recommended that AfDB should carry out one financial management supervision mission per year.

Furthermore, in its description of the project’s components, internal measures that contribute to the capacities of the implementing partner – such as training GIABA staff on the AfDB procedures in procurement and financial management – are included as an activity with a dedicated budget along with other more thematic activities aimed at the project beneficiaries, such as workshops on strategic analyses for financial intelligence units (see Figure 10).

Figure 10: Extract from project components of CD4AML/CFT

|

Component III: Support to GIABA implementation capacities for project management |

9. Support to GIABA on improvement of its internal capacities to better coordinate AML/CFT in W |

|

Total cost: UA357,000 |

|

Source: African Development Bank 2022

Example 3: Support Police Capacity Building in the Field of Public Order and Cybercrime in Moldova

UNDP is implementing the Support Police Capacity Building in the Field of Public Order and Cybercrime in Moldova project between 2024 and 2025 with funding from the US Department of State’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (UNDP 2024).

The project aims to ‘support the modernisation of law enforcement capabilities in Moldova, including mobility, outreach, protection, monitoring/surveillance, investigative and computing capabilities’.

Under the governance arrangements, the project beneficiaries (Moldova’s Ministry of Internal Affairs and General Police Inspectorate) are responsible for decision-making and the implementation of project activities, while the UNDP country office in Moldova plays a quality assurance and support role.

The project documentation indicates several anti-corruption measures have been mainstreamed throughout the project. This includes the application of UNDP’s internal policy on fraud and other corrupt practices and the requirement that all project staff undertake mandatory UNDP training courses on anti-corruption and ethics, as well as on the prevention of sexual harassment and sexual exploitation and abuse. Furthermore, the document contains a clause on the prevention of corruption by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and General Police Inspectorate and any other project partners, stipulating that donors are entitled to recover funds in such cases.

- The Geneva Centre for Security Sector Governance (DCAF 2022) defines ‘SSR as the political and technical process of improving state and human security by making security provision, management and oversight more effective and more accountable, within a framework of democratic civilian control, rule of law and respect for human rights.

- The term capacity building has been viewed as problematic by some voices (Harle 2024; Beart 2022) who argue that it can carry connotations of a colonial-like unidirectional transfer of knowledge from countries in the Global North to those in the Global South. Beart (2022) argues that the term can and should be repurposed to encompass more ‘knowledge sharing and multi-directional learning’ in a more balanced way.

- A more detailed consideration of the OECD recommendation and members’ implementation of it is provided below.

- The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) and the Thinking and Working Politically Community of Practice have pioneered a political economy analysis (PEA) approach notable for its emphasis on understanding and working with a political reality, including how best to engage with counterparts’ political incentives and preferences.

- However, in the context of mainstreaming anti-corruption into wildlife conservation, Martini and Kramer (2023) highlight the political sensitivities around the word corruption in some contexts, which can even put implementing partners at risk with their national governments and therefore make the case for using alternative language and approaches to integrate safeguards.

- The U4’s Per Diem Policy Analysis Toolkit (Vian and Sabin 2012) provides key considerations, indicators and templates to guide donors in determining per diem policies. For an example of a detailed per diem policy from a development agency, see USAID’s Performance of Temporary Duty Travel in the United States and Abroad.

- According to the project document: ‘[a] managing contractor (MC), appointed through a DFAT-managed tender process, will support Program delivery, including activity design, activity and program-level M&E, reporting on the Program’s activities and progress, and supporting the design, M&E and reporting of activities delivered by APS Agencies (including provision of gender equality expertise)’.

- The project’s eight target countries are Burkina Faso, The Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Sierra Leone, Togo and Comoros.