Query

Please provide an overview of corruption risks in the reconstruction process in Lebanon, the key anti-corruption reforms and mitigation strategies to counter corruption in the reconstruction process.

Introduction

In recent years, Lebanon has faced multiple overlapping economic and political crises. The country experienced a significant economic collapse, marked by depleted foreign currency reserves, sharp devaluation of the Lebanese pound, restricted access to personal savings and a 36.5% drop in GDP per capita between 2019 and 2021 (Mansour and Khatib 2021; Balian 2022; World Bank 2022a). In October 2019, mass protests, primarily driven by younger generations, erupted across the country. Protesters condemned sectarian based politics, systemic corruption and deteriorating economic conditions, demanding the government’s resignation and the dismantling of the power-sharing framework between the country’s 18 recognised communities (Khatib 2019; Assi 2021).

The crises were exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic and the Beirut port explosion in August 2020 (Nassar 2023). The explosion, caused by improperly stored ammonium nitrate, killed 218 people, devastated parts of the city and implicated senior Lebanese officials. However, they have so far avoided accountability as rampant political interference in the judiciary stalled the investigation (HRW 2021, 2023a, 2023b; DelGrande 2022; Freedom House 2024). In a 2022 survey, 89% of respondents expressed that the national government’s response to the explosion had ‘reduced’ or ‘significantly reduced’ their trust and confidence in the government (Nassar 2023).

Several international actors stepped in to support Lebanon. For example, in 2020, the European Union, the United Nations and the World Bank Group launched the Lebanon Reform, Recovery and Reconstruction Framework (3RF). Originally focusing on a people-centred recovery response to the explosion, the framework operates as a platform to drive reforms necessary for its reconstruction needs and to achieve a sustainable economic recovery (3RF 2024).

In the aftermath of the Hamas attack on Israel in October 2023, a military confrontation was initiated between Israel and Hezbollah along Lebanon’s southern border (World Bank 2024a; ACLED 2024). This escalated into a full-scale conflict by September 2024 and, as of early November 2024, the death toll from Israeli attacks was over 3,000, with over 1.3 million displaced people (Al Jazeera 2024; World Bank 2024b).

A US-brokered 60-day ceasefire deal took an effect in November 2024, requiring Israel’s military and Hezbollah to withdraw from southern Lebanon (Salame and Zilber 2024). Although the deal was violated soon after, as Israeli military pushed deeper into southern Lebanon, the ceasefire was thereafter largely upheld (BBC 2024; Salame and Zilber 2024). In January 2025, Lebanon’s parliament elected the military general Joseph Aoun as president following a two-year period in which the position was vacant (Christou 2025). In late January, the ceasefire was extended until 18 February (Aikman 2025).

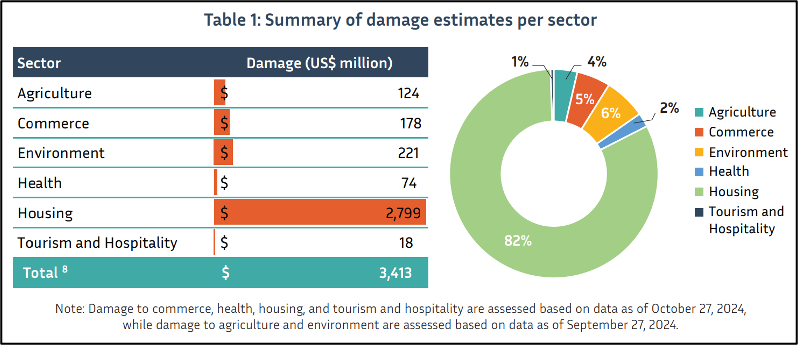

A World Bank (2024b: 5) interimfc15c16079f7 damage and loss assessment report estimated the conflict led to US$3.4 billion in damages to physical structures and US$5.1 billion in economic losses.8f79866c496f The housing sector in Lebanon was hit the hardest in the conflict, with nearly 100,000 housing units either partially or fully damaged, amounting to US$2.8 billion in losses (see Figure 1). The losses and damages primarily affected southern Beirut, south Lebanon and the Bekaa valley region where the bombing was concentrated (Christou 2025). As of late 2024, donors already committed over US$1 billion to address displacement caused by the conflict (Caulcutt 2024) and were beginning to make pledges towards reconstruction (Christou 2025).

Figure 1. A summary of damage estimates by sector in relation to the Israel-Hezbollah conflict

Source: World Bank 2024b: 6

Previous crises have demonstrated that reconstruction processes are vulnerable to corruption (Camacho 2023). This Helpdesk Answer examines the corruption risks relevant for the reconstruction of Lebanon, drawing from the different corruption drivers present in the country, the shape of its legal and institutional framework against corruption, as well as its existing experience with reconstruction. It then outlines some mitigation strategies that have been employed by international donors providing reconstruction aid to Lebanon.

Extent of corruption

Corruption in Lebanon is pervasive, permeating all levels of government (Freedom House 2024; BTI 2024).

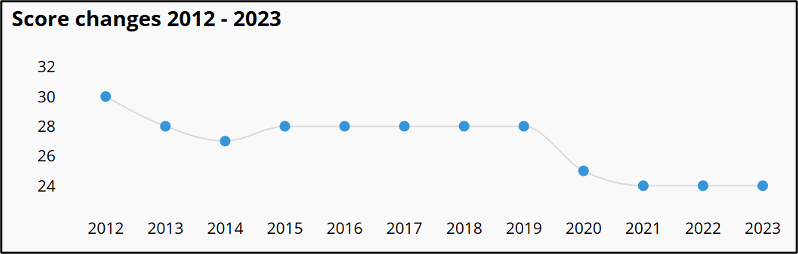

According to Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI) for 2023, Lebanon scored 24 out of 100, ranking 149 out of 180 countries and jurisdictions (Transparency International 2024). Following a slight improvement in its CPI score in 2015, and several years of stagnation thereafter, Lebanon’s CPI score sharply declined in 2020, and reached its lowest point (24 points) since 2012 in 2021, as shown in Figure 2 (Transparency International 2024; Hattar 2024). This drop has been attributed to the combination of recent crises and a political leadership vacuum which weakened resilience to corruption (Hattar 2024).

Figure 2: CPI score changes for Lebanon (2012-2023).

Source: Transparency International 2024.

Freedom House’s (2024) Freedom in the World report, classifies Lebanon as a ‘partly free’ country. One factor contributing to this rating was pervasive corruption, along with major weaknesses in the rule of law (Freedom House 2024). The latest Bertelsman Transformation Index (BTI) (2024) report similarly underscores the endemic nature of corruption in Lebanon, noting that public officeholders are rarely prosecuted or penalised for abuses of office. The report further observes that corruption and a weak rule of law contribute to blurring the lines between public and private property and that personal connections, based on sectarian loyalties, cronyism and nepotism, have reportedly become more prominent since the onset of the 2019 economic crisis (BTI 2024).

According to the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) for 2023, Lebanon’s scores declined across all indicators compared to 2013, except for political stability, which remained low. Lebanon’s score for control of corruption fell to -1.23 in 2023, down from -0.92 in 2013, reflecting a significant deterioration (see Table 1).aeed20dabd7a This indicator measures the strength of public governance based on perceptions of the extent to which public power is exercised for private gain (including both petty and grand corruption), as well as the capture of the state by elites and private interests (World Bank n.d. a). The score for government effectiveness similarly dropped sharply, from -0.31 in 2013 to -1.58 in 2023, placing Lebanon in the sixth percentile rank globally (World Bank 2024). This indicator measures the quality of public services and civil service, the degree of its independence from political pressures, and the quality of policy formulation and implementation, as well as the credibility of government’s commitment to such policies (World Bank n.d. b).

Table 1: Lebanon’s scores on the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) in 2013, 2018 and 2023.

|

2013 |

2018 |

2023 |

||||

|

|

Score |

Percentile rank |

Score |

Percentile rank |

Score |

Percentile rank |

|

Voice and accountability |

-0.41 |

35.21 |

-0.51 |

31.55 |

-0.65 |

30.88 |

|

Political stability |

-1.69 |

6.64 |

-1.62 |

7.08 |

-1.52 |

9.48 |

|

Government effectiveness |

-0.31 |

44.55 |

-0.67 |

25.24 |

-1.58 |

6.13 |

|

Regulatory quality |

-0.08 |

49.76 |

-0.45 |

34.76 |

-1.01 |

14.62 |

|

Rule of law |

-0.73 |

27.70 |

-0.78 |

22.86 |

-1.17 |

13.21 |

|

Control of corruption |

-0.92 |

19.43 |

-1.13 |

11.90 |

-1.23 |

10.85 |

Source: World Bank 2024

Corruption in Lebanon affects public trust in the government and reconstruction efforts. The latest survey by the Arab Barometer (2024: 3-4) suggests that Lebanese citizens consider corruption (29%) the second most important challenge facing the country, following the economic situation (33%). Trust in Lebanese institutions is the lowest among all countries surveyed by the Arab Barometer,946e392e4b4b while 76% of respondents expressed no trust at all in their government (Arab Barometer 2024: 12). In addition, 69% of respondents believe that the government is not working at all towards cracking down on corruption (Arab Barometer 2024: 17).

Drivers of corruption in reconstruction efforts

Social sectarianism

Sectarian power dynamics remains one of the key drivers of corruption in Lebanon, including in the country’s reconstruction process. Deeply entrenched patronage networks engage in the capture of institutions, attempt to block the implementation of recent anti-corruption efforts and engage in the politicised allocation of resources, such as through public procurement contracts.

The end of the civil war in Lebanon (1975-1990)e777bded9963 was marked by the 1989 Taif Agreement, which reorganised the country’s power-sharing system along confessional lines (Bahout 2016; Harb 2024). The agreement stipulates that the president of the republic has to be a Maronite Christian, the prime minister has to be Sunni Muslim and the speaker of the parliament has to be Shia Muslim. In parliament, the new agreement aimed to uphold Christian-Muslim parity, replacing a representation formula that had favoured Christians (Harb 2024). While Article 95 of the Lebanese constitution designates that the system should exist as a ‘transitional phase’, it remains in place (Salvatore 2022).

According to many commentators, the power-sharing system has entrenched sectarian interests and fuelled state capture, patronage networks and clientelism (Merhej 2021; Makdisi and Marktanner 2009; Salamey 2009; Wickberg 2012; Schoeberlein 2019).

However, it is important to note that many other scholars distinguish between forms of social sectarianism, which can lead to negative outcomes for different confessional groups at the expense of others, and consociationalism, which they view as a political system that can best manage Lebanon’s plurality. For example, Ghsoub et al. (2023) argue that a that a properly functioning power sharing system based on consociationalism can address the concerns of all groups, mitigate aggressive political competition, and foster stability.

The country’s three leaders (the so-called troika) often resort to informal decision-making to circumvent gridlocks, with their deals typically involving the apportioning of state institutions and resources among political parties focusing on different demographics (Majzoub et al. 2023: 37; Leenders 2012; Parreira 2020). This system, in turn, has reportedly resulted in strong ties between political and business figures,revolving door system between government and the private sector, and even led to politicians owning businesses (Majzoub et al. 2023: 37). Baumann (2016) also observes what they call the political economy of sectarianism in which a small, politically connected elite appropriates most of the economic surplus and redistributes it via its clientelist networks, noting how public contracts are typically allocated to companies tied to sectarian elites. Cortés and Kairouz (2023) argue that even in times of political crises, the position of political elites in office often endures and is cemented through intra-communal cohesion and clientelism.

Furthermore, in a practice known as muhassasa, many public sector positions are divided based on sectarian affiliations, rather than merit (Salloukh 2019). This coincided with the significant expansion of the public sector over the years, which grew from 75,000 employees in 1974 to around 300,000 in 2017 (Azour 2013; Salloukh 2019: 46; Saab 2019). According to a World Bank (2015: 44) diagnostic report, this method of staffing in the public sector inhibited the state’s ability to deliver quality public services efficiently as sectarian interests are prioritised over public interest, transparency and accountability.

These existing corruption risks naturally apply to reconstruction efforts which are grounded in public contracts and the provision of services. For instance, the councils and funds that manage compensation and reconstruction are suspected to have been coopted by political parties as a “means of distributing state funding from political patrons to their clients” (Forster 2022: 10).

Economic crisis

Since 2019, Lebanon has faced a fiscal and economic crisis that has resulted in depleted foreign currency reserves, a sharp devaluation of the Lebanese currency and Lebanese citizens facing constraints to access their savings (Mansour and Khatib 2021; Balian 2022). According to the latest World Bank (2024a) report, Lebanon’s cumulative decline in real GDP since 2019 was projected to exceed 38% by the end of 2024.

The management of public finances in post-civil war Lebanon has been vulnerable to fraud, according to the World Bank (2022b). The report states that public finances have been used to capture the country’s resources by instrumentalising state institutions through fiscal and economic tools (World Bank 2022b). In this system, excessive debt accumulation created an illusion of stability, encouraging continued inflows of commercial bank deposits (World Bank 2022b; Proctor 2022), while high interest rates attracted high inflows of remittances from Lebanese people living abroad. Further, the World Bank highlighted that a significant portion of people’s savings in the form of bank deposits was misused or misspent (World Bank 2022b; Proctor 2022).

Lebanon’s banking sector has been weakened by clientelism (Sabaghi 2023). The former governor of Lebanon’s central bank, Riad Salameh, and his associates were probed for allegedly transferring around US$330 million from the central bank to European countries between 2002 and 2015, which were used to purchase luxury real estate and other assets (Sabaghi 2023). In September 2024, Salameh was charged with embezzlement from the central bank (Chehayeb 2024). A 2014 study analysing the ownership and political affiliations of 20 leading commercial banks, found that 18 of them had major shareholders linked to political elites, collectively controlling 43% of assets in the commercial banking sector (Chaaban 2016).

The economic crisis will have implications for the reconstruction process. In response to economic pressures, Lebanese citizens have increasingly turned to political and sectarian actors to access basic services, which undermines efforts to centralise the provision of services (World Bank 2022b; Proctor 2022). Furthermore, due to banking sector vulnerabilities and other shortcomings, Lebanon was placed on the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) ‘grey list’ in October 2024 which may frustrate capital inflows (World Bank 2024a), including those in support of reconstruction.

Hezbollah and its informal networks

A hybrid political party and paramilitary actor,069febfb7a62 Hezbollah has been considered by several commentators to be a driver of corruption in Lebanon (Khatib 2021; Levitt 2024).

In the post-civil war period, the Iran-backed group has risen to become the most influential political actor in Lebanon, often operating without the accountability required of state institutions (Khatib 2021; Mansour and Khatib 2021). Evidence also suggests that Hezbollah has its stakes in both licit and illicit economies, ranging from narco-money laundering abroad to operating environmental NGOs within Lebanon (Levitt 2024).

Like other ruling parties in Lebanon, Hezbollah exerts control over state institutions and benefit from their resources, by distributing them to their own constituents (Khatib 2021). For instance, Hezbollah controlled the agriculture portfolio from 2009 to 2014, during which time its minister of agriculture was accused by the farmers syndicate of selectively distributing the benefits of government measures aimed at improving agricultural infrastructure (Khatib 2021). Moreover, between 2009 and 2014, OMSAR (Office of the Minister of State for Administrative Reform) was led by Hezbollah, during which it conducted a tendering process for a solid waste management project funded by the EU (Khatib 2021). According to Khatib (2021) Investigative reporting by TRT World uncovered allegations that a portion of the EU funds had been embezzled (Khatib 2021; Jay 2019).

Hezbollah provides social services, jobs, and welfare support in the regions it controls, primarily in southern Lebanon, parts of Beirut and the Beqaa Valley, thereby reinforcing the political clientelist system (Levitt 2024: 3). Hezbollah has stepped in to manage various crises in recent years in Lebanon (Ghaddar 2020). For example, it used its control over the Ministry of Health to coordinate with pharmacies in its strongholds, ensuring that its constituents received medication at lower prices (Ghaddar 2020).

Hezbollah is also a significant financial actor in reconstruction and more widely. The group also operates Al-Qard al-Hasan, which was established in 1987431535972588 and offers interest-free loans based on Islamic principles and is estimated to have hundreds of thousands of clients, many of whom sought loans in response to the economic crisis (Reuters 2024). Despite these financial activities, Al-Qard al-Hasan describes itself as a charitable organization operating outside the Lebanese financial system, meaning it is not subject to the supervision of the Central Bank of Lebanon.

Hezbollah has already positioned itself as a player in the reconstruction process following its conflict with Israel. It began mapping and surveying the damage as part of its reconstruction efforts, with the Jihad al-Binaa Development Foundation363cd8ccae9e – a Hezbollah lnked non-profit organisation - overseeing the rebuilding of infrastructure and construction under Hezbollah’s Executive Council. In early December 2024, Hezbollah pledged to support the reconstruction effort, announcing financial aid of US$14,000 per family to those whose homes were destroyed in Beirut and its suburbs, and US$12,000 to those whose homes were destroyed outside of Beirut, using funds it has framed as a gift from Iran (Frayer 2024). The lack of transparency over such funds arguably carries high corruption risks and may challenge donor efforts to establish accountability in reconstruction financing.

Main corruption risks in the reconstruction process

This section surveys the available evidence - largely drawing of previous experiences and studies- regarding the different corruption risks existing across the various stages of reconstruction efforts in the specific context of Lebanon.

Design and planning

Corruption can enter the design and planning phase in several ways. First, when damage assessments are unreliable or have been falsified, asymmetrical funding can be allocated for specific needs. A 2022 Lebanon Financing Facility (LFF) report describes the Beirut Housing Rehabilitation and Cultural and Creative Industries Recovery project implemented by UN-Habitat in response to the Beirut port blast (LFF 2023), noting challenges due to outdated, missing or inadequate housing data, requiring extensive data collection and verification (LFF 2023). The report further notes the complexities of housing in Beirut, recommending that thorough damage assessments and sufficient funding for surveys are provided in future projects (LFF 2023: 31).

Second, poorly designed monitoring and oversight mechanisms in a reconstruction project can lead to a failure to detect corruption. These controls may be overlooked given the need for a rapid response, but their absence creates corruption vulnerabilities. For instance, a RITE report attributed corruption in an EU funded waste management facilities project in Lebanon to poor management by the local implementing partner (OMSAR) and insufficient monitoring by the EU (RITE 2023). Specifically, the report highlighted poor selection criteria during the bidding process, insufficient support for performance monitoring of contractors and poor record keeping (RITE 2023). According to RITE (2023), these negative outcomes could have been avoided if monitoring and oversight had been properly planned and designed in advance.

Third, given the entrenched clientelist networks in Lebanon, a significant risk lies in the undue influence on resource allocation and the prioritisation of areas or items for reconstruction based on sectarian divisions, rather than actual needs. In this regard, a previous fieldwork-based analysis in Lebanon found that an aid related negotiation and planning process was not inclusive enough and stressed the need for the greater involvement of key stakeholders, such as civil society organisations, sectoral experts, private-sector partners and beneficiaries in the planning and allocation process (LCPS and OXFAM 2018).

Similarly, after the 2006 Israel-Hezbollah war, the Hezbollah-linked Jihad al-Binaa Development Foundation implemented the project Wa’ad to supervise and coordinate reconstruction in the Haret Hreik municipality in southern Beirut (Lob 2020). The reconstruction efforts were reportedly marked by a lack of public debate, transparency and accountability, and the intended beneficiaries later complained about the allocation outcomes, citing low-quality housing, uncleared debris and favouritism towards Hezbollah supporters (Lob 2020).

Public contracting

Weak oversight, the decentralised nature of public procurement, along with staffing based on sectarian divisions increase corruption risks in public contracting in Lebanon, which can lead to inefficient reconstruction outcomes, for example the purchase of constructions materials of an inferior quality or contracting inexperienced firms.

There is repeat evidence of the politicised allocation of public contracts in Lebanon. According to an analysis by the Gherbal Initiative, the top five same contractors received US$3.45 billion out of US$13.55 billion in government contracts between 2001 and 2020 (Salame 2022b). Some of these contractors were placed on the US sanctions list for ‘contributing to the breakdown of the rule of law in Lebanon’ (Salame 2022b).

A study by Mahmalat et al. (2021), focusing on the public procurement of large infrastructure projects between 2008-2018, examined how political connections influenced the value of awarded contracts. The study reviewed 394 contracts awarded by the Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR),fd192ae963ed valued at a total of US$3.98 billion, of which US$1.76 billion came from foreign funding (Mahmalat et al. 2021: 2). The study distinguished between two types of political connections of firms winning large infrastructure contracts: those connected with CDR board members or with the small number of sectarian elites that installed CDR board members, and those connected with any minister, MP or other party elite holding office in the analysed period (Mahmalat et al. 2021: 4). They found that firms with the former types of connections received higher contract values compared to the latter, as well as compared to non-connected firms (Mahmalat et al. 2021).

The Lebanese Ministry of Public Works and Transportation recently attempted to award a US$122 million contract for building a new airport terminal by avoiding competitive bidding (Mroue 2023). Following backlash from civil society and the media, the ministry retreated from the plans (Mroue 2023).

In 2021-202270db184060f4 a new Public Procurement Law (PPL) was adopted796d0eaf8a23 in preventing non-competitive procurements. However, an analysis covering August 2023 to August 2024 by the Gherbal Initiative found evidence of a high number of violations of the Public Procurement Law, from the announcement to the awarding stage, including failures to adhere to the required number of bidders without justification and violation of the legally prescribed timeframe granted to bidders to submit their proposals (Gherbal Initiative 2024: 74-80). The levels of lack of compliance with the PPL means that Lebanon’s current reconstruction efforts may still be exposed to compromised public contracting.

Service delivery

Corruption in planning and public contracting for reconstruction can trickle down and lead to the substandard or ineffective delivery of critical services such as construction, waste management and electricity sectors, ultimately at the cost of intended beneficiaries.

As noted, housing constitutes the most pressing reconstruction need for Lebanon. Kalakesh et al. (2025) carried out a qualitative study with construction firms involved in public infrastructure projects. Many of the respondents said that financial mismanagement in such projects leads to cost overruns, time delays and poor quality work.

Waste management is relevant for reconstruction in Lebanon not only for clearing debris caused by the conflict but for waste generated in construction works (Al Tawil et al. 2023). The aforementioned CDR concluded a contract with the waste management company Sukleen in 1994 to manage waste collection in Beirut and Mount Lebanon (from 1996) for US$3.6 million (Merhej and Ghreichi 2021; Chaaban 2015). This amount was estimated to constitute nearly double the cost of what municipalities would have charged for the same service. Nevertheless, this contract was renewed three times without an open tender, each time resulting in higher fees for collection and processing (Merhej and Ghreichi 2021; Chaaban 2015). Reportedly, Sukleen had strong business ties with a former prime minister, which Merhej and Ghreichi (2021) argue may have influenced CDR to award the contract to Sukleen.

Investment in the electricity sector is needed in Lebanon to restore power to affected communities and facilitating the effective construction of housing. According to Human Rights Watch, corruption has led to prolonged neglect of the sector (Majzoub et al. 2023). Although the state-owned Electricité du Liban (EDL) receives billions of dollars in subsidies yearly, power cuts are a regular occurrence in Lebanon (McDowall 2019). Faced with frequent power cuts, many households rely on private electricity suppliers, known as the ‘generator mafia’, to access electricity (Merhej 2021). Many of these private operators reportedly have strong political ties, which creates a mutual interest for politicians and private electricity providers in maintaining the status quo of weak state-owned suppliers (Merhej 2021; Majzoub et al. 2023). In 2020, the council of ministers appointed a new EDL board of directors, one of the key demands of international donors. However, these appointments were criticised as they were perceived to be based on political affiliations rather than merit (Merhej 2021: 55; Dakroub 2020).

Legal and institutional anti-corruption framework

Legal framework

Under pressure from civil society, international stakeholders and widespread protests, the Lebanese parliament passed a series of anti-corruption laws, including legislation on access to information, whistleblowing and public procurement. Additionally, in 2020, the government adopted Lebanon’s first ever national anti-corruption strategy for 2020-2025 (Khoury and Sonnier 2024). Nevertheless, political paralysis in recent years has reportedly slowed down the implementation of anti-corruption reforms (US Department of State 2024).

Recent legal reforms

This section considers the effectiveness of Lebanon’s legislation on public procurement, access to information and whistleblowing, all of which have the potential to constitute key transparency safeguards for future reconstruction efforts.

Procurement legislation

Until 2022, there was no specialised law specifically regulating public procurement (Khoury and Sonnier 2024) and the regulatory framework was fragmented, which led to inefficient spending and fostered a culture of non-transparency (World Bank 2020; OECD 2022).

The Lebanese parliament passed the Public Procurement Law (PPL) in June 2021, which came into force in July 2022 (OECD 2022). The PPL reorganised the institutional framework of public procurement with the overall goal of establishing a coherent system with clear mandates (OECD 2022: 12). The PPL brings all public entities under a consistent set of rules, governed by a single oversight authority, the public procurement authority (PPA). Additionally, the new legislation provides for a special authority to handle complaints, the Procurement Complaints Authority (PCA), although this body had not yet been established as of 2024 (3RF 2024).

The PPL also mandates the creation of tender and acceptance committees within each procuring entity to serve as internal control mechanisms (OECD 2022: 13). The former is tasked with assessing tender documentation, opening and evaluating bids, and determining the best bidder, while the latter assesses the quality of contract execution (OECD 2022: 13). The legislation sets standards for selecting the committees’ members with the aim of preventing politicised influence (Salame 2022).

The PPL also stipulates the establishment of a central electronic platform, which is intended to strengthen the transparency and integrity of the process (OECD 2022: 11). The PPL specifies thresholds for competitive procurement, outlines penalties for violations of procurement policies, and requires every authority to have a trained procurement officer (Khoury and Sonnier 2024: 3).

However, a study by the Gherbal Initiative (2024) found evidence of a low level of compliance with the PPL so far. Specifically, only 139 administrations issued procurement announcements in line with the PPL, although over 200 public administrations and institutions, around 1,100 municipalities and municipal unions, as well as many Lebanese diplomatic missions and embassies, are required to comply with the law (Gherbal Initiative 2024: 9). Furthermore, the initiative (2024) uncovered evidence that some contracts with the same subject and value were awarded multiple times to the same suppliers within one year, suggesting that contracting authorities were splitting contracts to avoid oversight by the court of audit and circumvent requirements for public tenders. Finally, they found that a quarter of the evaluated procurements were done via direct contracting, with the number of contracts concluded via this method increasing compared to the first year of PPL implementation (Gherbal Initiative 2024: 3). Khoury and Sonnier (2024: 5) state that, in spite of the PPL, many private-sector actors doubt the fairness of public contracting processes and therefore are reluctant to submit bids.

In 2023, a bill of amendments to the PPL were passed by parliament. The Secretariat of the inter-ministerial committee in charge of following up on the public procurement reform flagged corruption and transparency risks, including (Institut des finances Basil Fuleihan 2023):

- The requirement for non-Lebanese companies to obtain certificates of eligibility without a clear appeal mechanism in case of non-obtainment created a risk of discretionary power.

- Extending the timeline for publishing annual procurement plans by up to three months after the fiscal year created a risk that access to critical information would be delayed.

- Military and security entities were exempted from the requirement to submit and publish procurement plans.

- Giving the PPA the mandate to determine the criteria for the pre-qualification and classification of suppliers created risks of clientelism and limiting competition.

Although a group of MP members had filed an appeal to invalidate the bill, this appeal was rejected by the constitutional council, making the amendments now enforceable.

Access to information

The Right to Access to Information (RATI) Law was passed in February 2017, almost a decade after the draft law was first introduced (Ibrahim 2025). According to this law, any natural person or legal entity can request and access data and documents from Lebanese ministries, municipalities and other state institutions, including their budgets, decisions and documents detailing their activities (Chehayeb 2020; Barakat and Diba 2023). The law stipulates a 15-day deadline for responding to requests, which can be extended by another 15 days for complex requests (Chehayeb 2020). The law also mandates active disclosure, requiring municipalities and entities at other government levels to publish information online in a ‘searchable, copyable, and downloadable format’ (Ibrahim 2025; France 2022).

However, research on the implementation of the law highlights several challenges. In 2024, the websites of six ministries were assessed using the right to access to information index38e2e499d234 developed by Transparency International Lebanon. Their analysis revealed that only two ministries published documents that were searchable and downloadable, and only one ministry allowed the electronic submission of information requests and provided contact information for information officers (Ibrahim 2025). Another issue relates to a failure to respond to requests; the Gherbal Initiative (2022) submitted requests for information to 202 public administrations in 2022, and received only 108 responses, of which only 28 gave complete responses.

The effective implementation of RATI is reportedly hindered by under-equipped government agencies, insufficient financial and technical resources, inadequate infrastructure for handling and digitising data, and a general lack of public awareness regarding the importance of access to information (Ibrahim 2025). In 2020, the ministerial anti-corruption committee adopted the national action plan to implement the RATI law which had a two-year timeframe aimed at addressing the weak enforcement of the law (France 2022). However, after four years, a significant part of the plan has yet to be executed (Ibrahim 2025).

Whistleblower protection

The parliament passed the Law No. 83 on the protection of whistleblowers in 2018, which established a legal framework for exposing corruption in the public sector. The law covers all individuals holding public office, protects whistleblowers from retaliation by employers and imposes fines for anyone who retaliates against them (Saddy 2019; France 2022).

The national anti-corruption commission (NACC) is tasked with receiving information from whistleblowers, carrying out investigations into corruption allegations, providing legal and physical protection to whistleblowers, and determining compensation to be awarded (Merhej 2021: 19). The law also authorises NACC to issue rewards if the disclosure leads to the recovery of funds or the prevention of financial loss (Saddy 2019).

Despite the importance of this legislation in uncovering corruption in the public sector, the law reportedly does not provide whistleblowers with sufficient protection against defamation lawsuits (Chehayeb 2020). Furthermore, Article 5 of the law requires that the whistleblower’s full name, occupation, address, work address and phone number be included in the corruption disclosure, compromising guarantees for their anonymity. These gaps may combine to deter potential whistleblowers from engaging these channels.

Institutional framework

In recent years, new anti-corruption institutions have been established in Lebanon, including the national anti-corruption commission (NACC) and the public procurement authority (PPA). Along with existing bodies such as the court of accounts (CoA), the central inspection and OMSAR, these institutions have the potential to address systemic corruption and safeguard reconstruction processes. Nevertheless, poor coordination among these institutions, political interference, and a lack of financial resources and staff, have combined to limit their effectiveness (OMSAR 2020).

National anti-corruption commission (NACC)

In 2020, the Combatting Corruption in the Public Sector and the Creation of the National Anti-Corruption Commission Law (Law No. 175) established the NACC (Barakat 2023a). Its responsibilities include receiving corruption related reports, investigating them and referring cases to competent authorities for prosecution, monitoring the prevalence of corruption and raising awareness, and providing expert opinion on draft laws and policies related to preventing corruption (Barakat 2023a).

Additionally, the NACC is tasked with receiving complaints about non-compliance with the RATI law, as well as with processing and auditing asset and interest declarations (Barakat 2023a). According to the NACC’s Second Annual Report for 2023, the number of persons who submitted their asset and interest declaration reached 927 employees, comprising 540 public administration employees, 361 municipal council members and employees and 26 Judges (NACC 2024); in comparison, a total of 194 submissions were recorded in 2022 (NACC 2023). During 2023, the NACC issued 17 decisions disciplining non-compliance with the RATI Law (NACC 2024).

The NACC consists of two elected retired honorary judges and four members nominated by the bar associations (of Beirut and Tripoli), the Lebanese Association of Certified Public Accountants, the banking control commission, and the minister of state for administrative reform and approved by the government (Moghabat 2021).

Nevertheless, the NACC has faced significant delays in becoming fully operational. This included delays in the election of all its members, the adoption of rules of procedure and code of conduct,696536986386 and in transferring budget funds to the NACC (Barakat 2023a). The NACC has experienced recruitment challenges and, as of May 2024, only three out of the planned 85 personnel had been employed (Maharat Foundation 2024).

Public procurement authority (PPA)

The public procurement authority (PPA) was established under the Public Procurement Law as an independent administrative authority (Institut des finances Basil Fuleihan 2022). Its mandate includes (Institut des finances Basil Fuleihan 2021: 63-65; Institut des finances Basil Fuleihan 2022: 10-14):

- consolidating annual procurement plans received from procuring entities

- timely publishing of all announcements and notifications related to procurements, pre-qualification and awarding proceedings on the central electronic platform of the PPA

- preparing and submitting periodic reports on legal violations and shortcomings in all procuring entities

The board of the PPA consists of a chairperson and four members appointed by decree issued by the council of ministers, based on the prime minister’s proposal.

According to an assessment based on the public procurement scorecards,1c11b8bddbee the PPA faced certain operational challenges as of 2024, with insufficient resources, delays in the staffing process, the lack of an online training platform for staff and delays in establishing the e-procurement platform (Almoghabat and Boustany 2024: 5-6).

Court of accounts (CoA)

The court of accounts (CoA) was established under the Public Accounting Law in 1951 and acts as Lebanon’s supreme audit institution (Siren Associates 2020).

The CoA’s responsibilities include ensuring compliance with financial laws, examining the legality of financial transactions, addressing financial irregularities, supervising the proper use of public funds and conducting post-audit reviews for independent public bodies (Transparency International Lebanon 2023: 4).

If suspicious activities are identified during audits, the CoA is legally obligated to notify the central inspection board to investigate; the CoA is also mandated to directly forward cases involving financial irregularities or crimes to the director of public prosecution to commence legal action (Transparency International Lebanon 2023).

The World Bank (2020) recognised the critical role CoA could play in the oversight of reconstruction efforts, but noted its independence and capacity needed to be strengthened. Institutionally, the CoA is exposed to the executive’s interference, as its president is appointed by the council of ministers upon the prime minister’s recommendation (France 2022). In recent years, budget reductions for the CoA have hindered its effectiveness, particularly by limiting its ability to hire staff and procure necessary equipment (Transparency International Lebanon 2023; LFF 2023: 35).

Transparency International Lebanon (2023) has highlighted that the CoA primarily focuses on ex-ante audits - evaluating financial transactions prior to being finalised – while neglecting ex-post audits which would help the CoA detect overspending and evaluate the effectiveness of public expenditures (Transparency International Lebanon 2023). Furthermore, it found that many of the CoA’s documents are not readily available on their website, and the publication of audit reports is often significantly delayed (Transparency International Lebanon 2023).

Office of the Minister of State for Administrative Reform (OMSAR)

OMSAR was established in 1993 with the goal of reforming Lebanon’s public administration and planning development (Merhej 2021: 50). It is headed by the minister of state, but unlike other ministries, it plays a consultative role and can make no executive decisions, which limits its influence, including over reconstruction processes (Merhej 2021: 50). From late 2009 to 2014, OMSAR was headed by a senior Hezbollah official (Khatib 2019). However, in recent years it has become less partisan through support from external stakeholders such as the United Nations Development Programme and has become a focal point for public administration reforms, digitalisation efforts and anti-corruption initiatives (France 2022). OMSAR also initiated a number of draft laws, including RATI, the law to establish NACC, the amendments to the Illicit Enrichment Law and the Public Procurement Law, among others (Ahmad and Maghlouth 2016). Merhej (2021) notes however, OMSAR continues to contend with significant resourcing and staffing challenges.

Central inspection bureau (CIB)

The central inspection bureau (CIB) carries out periodic inspections related to public services and funds in Lebanon (Abouzeid 2021; Moghabat 2022). The CIB was established under the presidency of the council of ministers, and its jurisdiction extends to all public administrations and institutions (Moghabat 2022: 3).

In a 2021 interview, the president of the CIB, Judge George Attieh, outlined several challenges he faced after assuming leadership in 2017, including that the institution was disorganised, suffered from a severe staff shortage and that hiring decisions were largely controlled by the cabinet and sectarian political leaders (Abouzeid 2021). Despite Attieh’s requests for additional staff and expanded authority, these appeals went unanswered, and the number of inspectors on his team was less than half of what the law allows (Abouzeid 2021).

Nevertheless, some positive developments have been reported. Under the initiative of CIB, the country’s first e-governance system was established in 2021, named IMPACT (the inter-ministerial and municipal platform for assessment, coordination and tracking). This open data platform collects and publishes central and local government data (IMPACT n.d.). IMPACT has enabled the CIB to establish inter-institutional collaboration between roughly 20 ministries and 1,077 municipalities and support more effective crisis management, including in the aftermath of the Beirut port explosion (Siren Associates 2022a).

Judiciary

According to Freedom House (2024), the judiciary in Lebanon is not independent and is subject to political interference. The administrative judiciary, known as the state council, provides counsel on draft laws and monitors state institutions’ decisions to ensure their legal validity (Merhej 2021: 20). Members of the state council bureau are appointed by the decree of the cabinet of ministers, upon proposal of the minister of justice (Merhej 2021; ICJ 2018). Similarly, Lebanon’s civil judiciary is influenced by the executive. The high judicial council is responsible for overseeing the civil judiciary, but eight of its ten members are appointed by the executive branch (Merhej 2021: 21).

There has been evidence of pressure on the judiciary during corruption investigations, including smear campaigns against judges leading high-profile investigations and senior government officials attempting to stall investigations (BTI 2024). In the aftermath of the Beirut port explosion, its political allies and other officials implicated in the case reportedly tried to obstruct the investigation by filing over 25 requests to dismiss judge Tarek Bitar, the lead investigator (HRW 2023a, 2023b). The public prosecutor, Ghassan Oueidat – who was himself charged by Bitar in the port explosion case – filed a lawsuit against Bitar, effectively suspending the investigation, and ordered the release of all 17 suspects detained (HRW 2023a, 2023b). In early 2025, Bitar signalled his intention to continue the investigation by issuing summons through civil bailiffs to bypass Oueidat’s instructions to police to refrain from delivering arrest warrants or transmitting documents related to the case (Assaf 2025).

Other stakeholders

Media

Although press freedom is guaranteed by constitution, it is inconsistently upheld (Freedom House 2024). Lebanon's media landscape is among the most open and diverse in the region. However, media outlets largely depend on political patronage, wealthy individuals or foreign powers, resulting in some degree of self-censorship (Freedom House 2024). Furthermore, television stations and print media outlets often align with political parties (BTI 2024). Defamation laws are used to harass and target journalists, and there has been a visible tightening of restrictions on journalists with the deepening of economic and political crisis (RSF 2024; Freedom House 2024). For example, in 2024 a journalist was summoned for questioning by the Internal Security Forces Criminal Investigations Office allegedly in relation to an online video in which he criticised the Public Prosecutor Sabbouh Sleiman for suspending an arrest warrant issued as part of an investigation into the Beirut port explosion (Amnesty International 2024).

Since the Beirut port explosion in 2019, a number of independent media and investigative journalist outlets have been established or have grown in significance in Lebanon, often consistently reporting on corruption and public accountability issues (Ballout 2023). These include, but are not limited to, Raseef22, Daraj, The Public Source and Maharat News.

International stakeholders

Various international stakeholders, such as foreign development agencies and multilateral organisations, have contributed significantly to reconstruction efforts in Lebanon.

One of the leading examples has been the 3RF (Reform, Recovery and Reconstruction Framework), a joint initiative of the World Bank, European Union and the United Nations, Lebanese government and civil society organisations aimed at ensuring transparency, accountability and strong oversight in reconstruction efforts (Transparency International n.d.). The 3RF partners explicitly recognised that ‘while the 3RF model was originally developed specifically around the Beirut port explosion, it can also serve as a model for future programming tied to overseeing implementation, bridging trust gaps, and bringing actors together’.

The 3RF is grounded on the idea that, for reconstruction to succeed, efforts need to be undertaken to restore the public’s trust in the national government, including by fostering more collaborative governance and empowering civil society (World Bank 2020). The framework came after multi-stakeholder consultations, including 40 stakeholder feedback and engagement meetings (Barakat 2023b). The 3RF independent oversight board oversees the implementation of the initiative and includes representatives from donor countries and six civil society organisations (CSOs) (3RF 2024).a5fad64a5d83

The framework pursues two core tracks, one that supports the immediate needs of vulnerable populations and small enterprises affected by the explosion in the short term and another one addressing long-term governance reforms and reconstruction challenges (Barakat 2023b). To finance this, 3RF partners also established in 2020 the Lebanon Financing Facility (LFF), a five-year multi-donor trust fund (World Bank 2021). It focuses on three key areas: socio-economic and business recovery, preparing for reform and reconstruction, and coordination, monitoring, accountability and oversight (World Bank 2021). Due to the political vacuum in the aftermath of the explosion, the LFF prioritised interventions implemented through the UN, NGOs and private-sector intermediaries rather than the government (World Bank 2021). However, the LFF recognised a potential future shift toward state-led implementation, depending on the progress of reforms (World Bank 2021).

In terms of the reconstruction in response to the Israel-Hezbollah conflict, bilateral donors such as France and other international actors were currently engaging with the Lebanese government on commitments as of January 2025, but the potential use of trust fund administered with the support of the World Bank to channel and manage reconstruction aid had reportedly gained traction (KUNA 2025).

Civil society

Lebanon has one of the freest civil society environments in the Middle Eastern region (BTI 2024). However, NGOs can sometimes face bureaucratic obstacles or intimidation by security services (Freedom House 2024).

CSOs active in the field of anti-corruption include:

- Gherbal Initiative, a government transparency watchdog actively involved in monitoring the implementation of the new procurement legislation. They created a designated website to monitor the transparency and implementation of the new Public Procurement Law, in cooperation with the Middle East Partnership Initiative. The platform enables contractors and other citizens to inform themselves about tender opportunities, divided by regions, administrations and sectors. They also organise training courses and workshops in cooperation with Institut des finances Basil Fuleihan (Gherbal Initiative 2024; Salame 2022).

- Lebanese Centre for Policy Studies (LCPS) is an independently managed and non-partisan thinktank advocating for governance reform policies in Lebanon and the Arab region.

- Transparency International Lebanon is an anti-corruption NGO. In the aftermath of the Beirut port blast explosion, it spearheaded the Transparent Hearts initiative to ensure high levels of transparency and accountability in reconstruction projects implemented by CSOs in Lebanon.

Mitigation strategies for international donors providing reconstruction aid to Lebanon

This section highlights measures international donors can take to mitigate the corruption risks in reconstruction aid, drawing from a small body of literature which has produced recommendations for the case of Lebanon specifically.

Adopting a preventive and strategic approach is important to mitigate corruption risks associated with the provision of reconstruction aid (Camacho 2023). Broadly speaking, mitigation strategies can be built into the day-to-day implementation of reconstruction interventions and inform the very modalities used to channel aid.

Official estimates show that Lebanon received more than US$16 billion in grants and loans between 1992 and 2021 (Merhej and Ghreichi 2021). However, the Lebanese government’s history of managing international grants and loans has been controversial, characterised by a lack of transparency and accountability, poor monitoring and evidence of fund misuse (Merhej and Ghreichi 2021; RITE 2021). Therefore, international donors intending to support Lebanon’s reconstruction are confronted with critical decisions on how best to channel their aid in light of the corruption risks and institutional gaps (Mahmalat et al. 2022).

In the immediate aftermath of the Beirut port blast, where hundreds of thousands of people were left homeless, the international community pledged to provide around US$300 million in emergency assistance (Merhej and Ghreichi 2021). Nevertheless, some donors stated that they would bypass the state to deliver the aid through trustworthy local partners or international organisations (Vohra 2020; Merhej and Ghreichi 2021). For instance, the US Agency for International Development sent emergency medical kits directly to hospitals, avoiding the Ministry of Health (Vohra 2020).

Similarly, Human Rights Watch (2020) expressed scepticism about the Lebanese government’s ability to distribute aid to those in need and instead suggested creating a funding consortium to pool emergency aid into one fund and then allocate it among organisations that meet strict standards of transparency and respect for human rights. The 3RF partners set out high transparency and financial management standards that CSOs must meet to that receive reconstruction funds (Uwaydah 2021).

However, only relying on non-state institutions carries a risk of further hollowing out and weakening Lebanese state institutions. Therefore, while its funds are currently only distributed to non-state actors, the LFF (2023: 34) engages in strengthening domestic institutions and enhancing the capacity of both central and local governments in Lebanon. Namely, it aims to build the capacity for a transparent, accountable and inclusive institutional framework for Lebanon’s reconstruction, by:

- strengthening Lebanon’s oversight institutions (court of accounts, central inspection bureau and national anti-corruption commission)

- building an effective public investment management system

- strengthening the capacity of the PPA (LFF 2023: 34)

According to Heller (2023), donor interventions in Lebanon can be uncoordinated, partly because the country lacks a central organising body for coordinating and planning assistance. A fieldwork study by LCPS and OXFAM (2018) found that the absence of a single government interlocutor to represent the Lebanese government often led to the duplication of aid related negotiations, causing confusion on the part of the donors. Indeed, a lack of clarity may cascade down to the beneficiaries. A February 2023 survey of aid beneficiaries in the area affected by the Beirut port explosion noted issues with transparency and accountability. Specifically, 47% of the interviewed beneficiaries who received aid reported there was not grievance mechanism they could use to make complaints, while 34% said they did not know if there was one (Dagher et al. 2023: 15). Moreover, 79% of respondents stated that aid providers did not respond to their requests for information (Dagher et al. 2023: 17). Having a central organising body for coordinating assistance can be an important mitigation strategy in itself; in this vein, the 3RF was developed to address coordination challenges following the Beirut port explosion.

Mehrej (2021) outlines three key recommendations to international stakeholders to safeguard their funds to Lebanon from corruption:

- Transparent funding processes: donors should make all their data easily accessible by media outlets, CSOs and fellow donors.

- Support for monitoring and oversight agencies: Donors should establish partnerships with Lebanon’s monitoring and oversight agencies and jointly devise programmes to strengthen their capacities.

- Support for independent media outlets and watchdog groups: donors should support some of the independent media and investigative journalism media outlets and watchdog groups that emerged after the 2019 port explosion with the aim of increasing public accountability.

Donors and their implementing partners can adopt standards and ways of working that enable greater transparency and oversight in reconstruction projects in Lebanon. RITE* (Reform Initiative for Transparent Economies) assessed 16 EU supported solid waste management facilities in Lebanon, which cost at least €30 million. These facilities were intended to provide environmentally friendly solutions and improve waste management for residents, but reportedly led to a waste of funds (RITE 2023; Deeley 2024) The project was conducted through the EU’s implementing partner, OMSAR. According to the RITE report, the waste of funds could have been avoided with better oversight by the EU and improved management by OMSAR (RITE 2023).

Although the EU said it had not found evidence of corruption, the RITE report (2023) argued that risks were not sufficiently mitigated. It highlighted poor selection criteria during the bidding process, inadequate record keeping and insufficient support for performance monitoring; for example, OMSAR failed to verify if contractors fulfilled their contractual obligations, thereby increasing risks of fraud and overcharging.

Considering these findings, the RITE report (2023: 11-16) proposed several mitigation measures for future projects, which may serve as a useful operational guidance for international donors:9d514c7e9f9f

- improve controls of project outcomes

- develop a result-based implementation framework, clarifying roles and responsibilities of each stakeholder, and outlining how progress will be measured

- ensure close monitoring of as many project aspects as possible, which the report claims is particularly relevant in Lebanon, to make sure that funds are used as intended, and that they reach their intended audience

- implementing partners should set clear internal performance targets, establish lines of accountability, and make sure to monitor and enforce them

- conduct regular independent expert supervision and monitoring of project implementation and follow up on the findings

- mitigate against fraud and poor management

- withhold payments to contractors until rigorous monitoring data about performance is available and, if possible, digitise data gathering and reporting, as this would help reduce false reporting

- conduct due diligence on potential implementing partners to ensure they have the necessary experience, a track record of successful projects, and compliance with laws

- require implementing parties to have rules regarding conflicts of interest which are actively monitored

- set up a robust fraud reporting system, for example, a whistleblower platform set up by the funders

- use financial management systems and electronic payments to improve transparency and reduce the risks of fraud

- use independent monitors and auditors to provide added financial oversight

- improve transparency and accountability

- publish all documents related to the project implementation on a designated website

- publicly report any findings of corruption as well as on the follow-up action

- deny repeat business to entities that demonstrate poor performance or bad faith on other projects

- improve the procurement process

- retain control over bidding and contracting processes

- conduct past-performance assessments for companies and implementing partners as a pre-qualification process for bids and disqualify from bidding those with a track record of poor project performance

- motivate performance and improve monitoring

- regularly monitor and enforce performance standards

- provide financial incentives for good performance and apply deductions for missed targets

- when possible, rely on data management technology to monitor the accuracy of fees being charged by contractors as these are vulnerable to fraud

- This estimate covers available data from the period between 8 October 2023 and 27 October 2024 for the commerce, health, housing, and tourism and hospitality sectors, and the period between 8 October 2023 and 27 September 2024 for the agriculture and environment sectors (World Bank 2024b: 5).

- The World Bank (2024b) has stated it will conduct a more comprehensive needs assessment ‘with the government of Lebanon, the EU, UN agencies, and other development partners once the situation allows and the government indicates its readiness to proceed’. This assessment will form the basis of a reconstruction and recovery strategy.

- Scores range from -2.5 to 2.5 (higher scores correspond to a better governance) (World Bank 2024).

- Their surveys cover Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Palestine, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Tunisia and Yemen. (See: Arab Barometer n.d.).

- This Helpdesk Answer does not address the historical development of sectarianism in Lebanon prior to the end of the civil war (1975-1990). For details about the period prior to 1990, see, for example: World Bank 2016, Bahout 2016, Harb 2024 and Merhej 2021.

- Hezbollah has been designated a terrorist organisation by select countries and entities.

- Al-Qard al-Hasan is registered with the Ministry of Interior, which issued receipt notification No. 217/A.D.

- The Jihad al-Binaa Development Foundation is registered with the Ministry of Interior under No. 239/AD. Jihad al-Binaav has ties to Iran’s Jihad al-Binaa umbrella organization and has been under U.S. sanctions since 2007.

- The CDR is a formally independent institution established in 1977 to oversee reconstruction and development projects in Lebanon and since 1993 played a central role in planning and executing large infrastructure projects. However, some commentators have characterised it as vulnerable to political influence (Mahmalat et al. 2021: 2).

- Please refer to the section on the legal and institutional anti-corruption framework for the description of the public procurement legislation in Lebanon.

- Please refer to the section on the legal and institutional anti-corruption framework for the description of the public procurement legislation in Lebanon.

- This index evaluates proactive disclosure across several categories, including the publication of information in accessible formats, the proactive disclosure of key documents, the ability to submit information requests electronically and the availability of contact details for assigned information officers (LCPS 2024).

- However, on 4January 2024, the Lebanese State Council approved the internal regulations, code of conduct and organisational structure of the NACC.

- Scorecards are based on 31 success indicators aimed to assess the levels of progress of four types of strategic objectives of the procurement reform in Lebanon: i) ‘bring the regulatory and policy framework in line with good international practices’; ii) ‘create an institutional framework for successful procurement management and build corresponding capacity’; iii) ‘economy and efficiency in procurement operations and practices’; and iv) ‘promote accountability, integrity and transparency in public procurement’ (Almoghabat and Boustany 2024: 1-4).

- As of late 2024, these were Nusaned, Lebanese Centre for Human Rights and Lebanese Association for Taxpayers’ Rights, and three vacant seats were in the process being filled (3RF 2024).

- Due to space constraints of this Helpdesk Answer, the description of the mitigation strategies proposed in RITE report (2023) is not exhaustive, but emphasises the most important aspects for corruption mitigation, as assessed by the author of this Helpdesk Answer. For the full description of all mitigation recommendations, please refer to the RITE report (2023: 11- 16).