Query

Please provide a summary of Russian links to corruption in Moldova, highlighting any recent cases.

Caveat

Many of the names of individuals and places referenced in this Answer have alternative spellings depending on how they have been transliterated into the Latin alphabet. In such cases, one version of the name is used here for the sake of convenience and without prejudice to the alternatives.

Introduction

Under the current administration led by Vladimir Putin, Russia has demonstrated a keen foreign policy interest in Moldova, seeking to influence Moldovan policy in different areas such as energy, politics, security and trade. Russia advances these interests through open and conventional channels like diplomatic relations, economic agreements and cultural and media influence, and through more opaque, harder-edged channels, such as military pressure or work conducted by intelligence services.

Moldovan state actors and Western voices have argued that the Russian state also deploys corruption as a tactic to advance Russian interests, often labelling this method as ‘strategic corruption’. Lang (2024) defines strategic corruption as:

‘[A] state agent’s use of financial or other means to incentivise a public power-holder in another country or international organisation to abuse their entrusted power for the strategic gain of the corrupting state.’

This may manifest, for example, as foreign state-owned enterprises bribing domestic officials in the target country to win concessions in a strategic sector of the economy, or a foreign government providing funding to allied factions in the target country in breach of political finance laws. However, not all acts of corruption that implicate foreign actors point to the existence of some underlying strategic objective on the part of that foreign government. A foreign business may bribe officials to win a contract primarily for the economic reward, rather than as part of a coordinated plan in service of geopolitical goals.

This Helpdesk Answer attempts to shed light on the extent and nature of Russia-linked corruption in Moldova and seeks to explore the extent to which we can describe Russian influence as amounting to strategic corruption. First, there are brief overviews of Russia’s foreign policy interests in Moldova and of the literature on strategic corruption. This is followed by a description and analysis of several prominent cases that have occurred in Moldova in recent years that seem to point to the existence of corruption with alleged links to Russia. Finally, the Answer considers different stakeholders’ proposals for strengthening Moldova’s domestic anti-corruption frameworks to guard against such threats.

At this stage, three caveats are highlighted:

- Corruption schemes in any given country (especially when complex in nature) may implicate actors from a multitude of other countries, including both state and non-state actors. While this Answer focuses on Russian actors and Moldovan actors sympathetic to Russia’s interests, it is acknowledged that other non-state actors from other countries and indeed foreign governments may also contribute to corruption and other opaque financial activity in Moldova. For example, schemes that have affected Moldova have been (at least in part) facilitated by or implicated actors ranging from Lithuanian banks and media providers (LRT 2024; OCCRP 2017a) to shell companies registered in the Bahamas (Zămosteanu 2024a), Latvia and the UK (LSM.lv 2018; Whewell 2015), Azerbaijani and Austrian businesses (Gulca and Mădălin Necșuțu 2021), bank accounts domiciled in Kazakhstan ((Zămosteanu 2024b) and even to Syrian diplomats (Serviciul de Informaţii şi Securitate al Republicii Moldova 2015), among many others.

- Moldova has recently struggled with high levels of corruption and the outsized influence of oligarchs, issues which have been viewed as key obstacles to the EU accession process (Meister 2024). Again, while this Answer focuses on Russian influence, it does not attempt to place this within the wider corruption landscape in the country. For a comprehensive overview of corruption in Moldova that focuses more on the domestic angle, readers are invited to read a previous Helpdesk Answer published in 2022.

- This Helpdesk Answer relies on publicly available evidence, which necessarily entails certain limitations. For example, the often clandestine nature of corruption networks can help obscure links between state and non-state actors, meaning key evidence may not be available in the public domain. Further, the Answer makes reference to several cases or allegations, some of which are the subject of ongoing investigations and judicial processes. The accounts given here reflect an effort to draw on what information was publicly available up to the date of publication without prejudice to any developments which may arise subsequently. Neither Transparency International nor U4 take a position on the veracity of the allegations discussed here.

Background on Moldova

Corruption in Moldova

The Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic existed for more than 50 years as an independent parliamentary republic under the Soviet Union until its collapse in 1991, whereafter Moldova declared its independence. In the decades that followed, as with other so-called post-Soviet states, rapid privatisation of state-run entities gave rise to a local ‘oligarch’f738b1fd282c class that established a foothold in key sectors such as media, transport, construction and finance and consolidated close clientelist relations with political figures and their families (Marandici 2021). This led many Western observers to associate Moldova with state capture and systemic levels of corruption up until the 2010s (CEPPS 2024: 32).

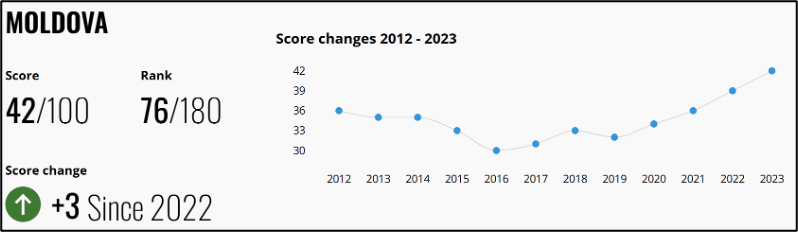

Moldova continues to contend with moderately high levels of corruption (see Figure 1), but a range of anti-corruption reforms have been initiated after the victory of the Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) in parliamentary elections in 2021, and the election and re-election of the PAS founder, Maia Sandu, as president in 2020 and 2024 respectively (Merkle 2022). Nevertheless, some of these reforms have stalled, with some commentators attributing this to persistent political interference from judicial actors, while others have argued some of the reforms are disproportionate and targeted against political opponents (Merkle 2022; Harward 2024).

Figure 1: Moldova’s rating on the corruption perception index (2012–2023)

Sourced from Transparency International n.d.

Corruption is very much a live topic in Moldova given that further integration with European institutions is conditional on the successful implementation of governance reforms. Sandu and PAS support Moldova’s accession to the European Union; in June 2022, the European Commission recommended that Moldova be granted candidate status, stipulating full membership should be subject to it fulfilling various criteria including ‘eliminating the excessive influence of vested interests in economic, political, and public life’ (CCIA 2023b). In October 2024, a referendum was held to amend the constitution to ground Moldova’s commitment to the accession process; the amendment passed, but only by a slim margin of 13,000 votes (Rainsford and Gozzi 2024).

Relations with Russia

Since Moldova achieved independence in 1991, Russia has remained a key foreign actor in the country in several respects. In 1992, the Russian military provided support to insurgents in the region of Transnistria who aimed to secede from the Moldovan state. Since the ceasefire was established later that year, 1,500 Russian troops have been stationed as a peacekeeping force in Transnistria. The region is de facto administered as a breakaway state with its own elections and political parties but remains internationally recognised as part of Moldova.

After the full-scale Russian invasion of neighbouring Ukraine in February 2022, Moldova’s position at a crossroads where Western powers and Russia vie for security influence became even more immediate (CCIA 2023b). Neutrality is enshrined in Moldova’s constitution and is currently supported by the majority of citizens; nevertheless, Moldova has forms of cooperation with NATO which has reportedly angered the Kremlin, which fears losing what it considers to be its security prerogative in the region (Samorukov 2024).

In 2023, Russia revoked its prior commitment to respect Moldova's sovereignty in resolving the future of the Transnistria region (Tanas 2023). In the same year, Ukrainian President Zelensky said the Ukrainians had intercepted intelligence pointing to a potential military action in Transnistria involving forces of the Russian federation (Locoman 2023). While this did not materialise, in 2024 the congress of Transnistria passed a resolution appealing to the Russian parliament (the Duma) to ‘implement measures for defending Transnistria amid increasing pressure from Moldova’.

Related to security, the political dimension of Russian interests also converges with cultural factors. Due in part to the influence of Russification policies during the Soviet era, the majority of Transnistrians speak Russian as a first language and almost half have Russian citizenship (Place 2024). In another autonomous region in Moldova – Gagauzia – most residents also speak Russian as a first language, with use of the local Turkic Gagauz language in decline (Colesnic 2024).

People living in both regions often vote in favour of what are considered to be pro-Russian parties in contrast to so-called pro-Western parties, although this tends to be nuanced in practice. Furthermore, such sentiments are far from limited to these two regions, and cultural affiliations to Russia and support for pro-Russian parties are present throughout the country. For example, Moldova’s second largest city of Bălți and the district of Orhei also associated with pro-Russian sympathies (Harward 2024). While the population in Gagauzia can vote directly in Moldovan national elections, residents of Transnistria with Moldovan citizenship often need to travel outside the region to do so.

Figure 2: Map of Moldova highlighting the geographic locations of Gagauzia and Transnistria

Sourced from Peña-Ramos and Amirov 2018: 501

In March 2023, the Moldovan parliament passed a bill stating that the official language spoken in Moldova is Romanian, which attracted explicit criticism from the Kremlin (Locoman 2023). Further disagreements over tax and freedom of movement regulations have been have cited by some political figures in Gagauzia and Transnistria as evidence of mistreatment by the authorities in Chișinău and as a reason to turn to Russia (International Crisis Group 2024).

Another significant dimension of Russia’s influence in Moldova concerns economic interests. In the decades following independence, some Russian businesses secured a strong influence over certain markets, to a degree that some have called a monopoly; for example, the Russian company Trans-Oil reportedly gained control over virtually all grain exports processed through the Giurgiulești International Port (Gulca and Necșuțu 2016).

Russian dominance in the energy sector has likewise resulted in Moldova’s dependence on Russia to serve its energy needs. For example, when Transnistrian authorities privatised one of Moldova’s largest power stations, it was sold to the Russian company Inter RAO (Peña-Ramos and Amirov 2018: 503). Russia, largely through its state-controlled natural gas entity Gazprom, remains responsible for most of Moldova’s gas needs and is also the main shareholder of Moldovagaz, which is responsible for gas distribution in the country (Secrieru 2021). In 2022, Gazprom cut supplies to Moldova, leading to a temporary energy crisis (Belton 2022) and has also claimed that the government owes it significant historic debts (Necșuțu 2023)

In recent years, Russia’s trade ties to Moldova have been dwindling, especially since the imposition of economic sanctions against Russia since the invasion of Ukraine in 2022, and Chișinău has moved closer to the EU, which is now Moldova’s main export partner (Ruy 2018). However, for many Moldovan oligarchs, economic allegiances are not clearcut; for example, the most powerful figure in Transnistria is widely considered to be Viktor Gushan, who reportedly strives to maintain positive relations with both Western countries and Russia to benefit his company Sheriff Enterprises (Harward 2024),

Furthermore, Preașca (2022a) points out that while the role of Russian capital is no longer as dominant in Moldova as in the 1990s, it continues to play a significant role in certain sectors such as gas, energy, oil, transport and media. He also notes how Moldova has increasingly served as a transit and destination country for Russian individuals or companies seeking to benefit from financial secrecy.

If and how all these dimensions tie into an exact, coherent Russian strategy in Moldova can be difficult to discern given that governments rarely disclose the full scope of their ‘realpolitik’. For Samorukov (2024), Russia’s primary geopolitical interest in Moldova is to undermine pro-European reforms and prevent what it perceives as a further decoupling from Russian interests. The European Commission (2024) has commended Moldova for its resilience against ‘intensified hybrid actions from Russia and its proxies seeking to destabilise the country’. President Sandu has also framed Russia largely as an adversary of Moldova and its ambitions to join the EU (International Crisis Group 2024).

In 2023, RISE Moldova, an independent consortium of journalists, reported about a leak of a document titled The Strategic Objectives of the Russian Federation in Moldova, which the consortium estimated to have been drafted in 2021 by the Foreign Intelligence Service of the Russian Federation (Zămosteanu et al. 2023). This document reputedly sets out the strategic goals of the Russian state, including that Moldova become integrated into the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) and Eurasian Economic Union – both bodies strongly linked to Russia – as well as highlighting the continued importance of promoting Russian gas, media and NGOs in the country, and protecting the Russian language and religious ties (Zămosteanu et al. 2023). Russian authorities do not appear to have commented on the validity of the document.

Core concepts

The potential role of foreign actors in driving domestic corruption is well recognised; indeed, this forms the backbone of key anti-corruption milestones, such as national and international foreign bribery legislation that penalises individuals and companies from one country bribing domestic public officials in another country (Gauthier et al. 2020). Beyond bribery, foreign actors may engage in other forms of corruption, notably undue influence, conflict of interest, violation of political finance regulations and the transfer of illicit financial flows deriving from (or enabled by) corruption. The unifying factor behind such offences is – expanding upon Transparency International’s definition of corruption – that they constitute an abuse of entrusted power by a domestic public official in furtherance of a private gain which is supplied by a foreign actor (normally with a view to advancing their own economic interests).

In recent years, an analytical model has gained traction in the literature that foregrounds potential foreign policy or geopolitical motives behind corruption. This has been referred to as ‘corruption as statecraft’ (Transparency International Defence & Security 2019: 9) and ‘weaponised corruption’ (Murray et al. 2021), but is most commonly called ‘strategic corruption’.

Lang (2024) explains that strategic corruption can be attributed back to a state principal pursuing a geopolitical interest, although this principal may rely on non-state actors who are themselves pursuing self-enrichment. This can include interest groups, companies and individuals that may have close ties with the principal (Bak 2021: 3). However, strategic corruption does not necessarily need to result in a clear economic benefit to the principal, and the advantage gained may be geopolitical in nature (Dolan 2024).

Nevertheless, it can be difficult in practice to causally attribute an act of corruption committed by a domestic public official all the way back to a state principal and their foreign policy objectives (Bak 2021: 3), especially in the presence of one or more non-state intermediaries (whose very role in a corruption scheme may have been encouraged to obscure the involvement of the state principal).

This means accusations of strategic corruption are not always easily substantiated, which can create tensions between the countries on either side of the accusation (Bergin 2022). Lang (2024: 316) also notes a risk of overstating the role of foreign actors at the expense of addressing the domestic actors who actually perpetrate the corrupt acts. In other words, strategic corruption is ultimately made possible by weaknesses in the targeted country’s anti-corruption framework.

Lang also argues that the practice of strategic corruption is not new – citing the example of European colonial powers strategically bribing local elites to acquire land – but that the discourse around it has evolved, reflecting a ‘securitisation of the corruption problem which for several decades was primarily framed as a socio-economic problem’. As a securitised issue, the discourse around strategic corruption can take on a politicised and polarising tone. This is perhaps unsurprising given that if state principal is successful in their aims, it can enhance their influence over target countries and have a destabilising effect on them (Baez Camargo and Kassa 2024).

In this vein, the concept of strategic corruption has increasingly been wielded by Western countries as a means of criticising influence-peddling and interference by countries they perceive to be their adversaries (Pozsgai-Alvarez 2024). For example, the United States has stated (White House 2024):

‘Authoritarian actors like Russia and the PRC [People’s Republic of China] use bribery to interfere in the policy, procurement, debt, and electoral processes of other countries – undermining both sovereignty and democracy.’

However, for many commentators, the concept of strategic corruption accurately reflects a tactic used by Russia under the administration of Vladimir Putin to influence public officials in other countries (Dolan 2024; Murray et al. 2021). They argue that acts of strategic corruption are carried out by state agents, such as the Russian intelligence services, as well as private business figures and oligarchs, many of whom have been co-opted into supporting Putin’s regime (Markus 2022).

To better illustrate this perspective, Table 1 reproduces the typology developed by Murray et al. (2021) on how they argue Russia uses weaponised corruption.

Table 1: Murray et al. description of Russia’s use of strategic corruption

|

Goals & Outcomes |

|

|

Strategy |

|

|

Tactics |

|

Sourced from Murray et al. 2021

Since the emergence of the discourse around strategic corruption, some observers (Rupert 2023; Doran and Stradner 2023) have applied the concept specifically to how Russia advances its various geopolitical influences outlined above in Moldova. Indeed, according to Jensen and Rupert (2024), ‘Putin’s main tools for destabilising Moldova’ are Russia’s continued influence over Gagauzia and Transnistria and the weaponisation of corruption. Nevertheless, such observers have typically not provided specific examples of what they consider to be cases of strategic corruption in the country.

Overview of cases

This section describes four cases from Moldova that could constitute acts of corruption linked to Russian actors. The following section then analyses the extent to which available evidence about these cases indicates that they would qualify as instances of strategic corruption.

These cases were selected with a view to reflecting different forms of corruption and different vectors of Russian influence. Cases that did not pertain to Moldova and its public officials were not considered; for example, the Moldovan national Alexandr Okulov has been linked to a Russian oligarch, but their allegedly corrupt activities have largely been carried out in third countries across Africa (Preașca 2022c). Another investigation suggested a Moldovan national was operating a business transporting crude oil from Russia in violation of sanctions, but there appears to be no claim of collusion on the part of Moldovan public officials (Preașca 2023a.) Similarly, cases where there was no ostensible or only a weak link to Russia were not considered; for example, the ‘Grand Theft’ case from 2014, in which US$1 billion in non-performing loans was fraudulently removed from three Moldovan banks (see Rață and Dodon 2018; Erizanu 2023).

These four cases involve many of the same key individuals; this is perhaps not surprising given that the most publicised cases tend to revolve around high-profile and politically exposed individuals. The cases should be considered a non-exhaustive list of potential cases, given the deep political and trade ties between Russia and Moldova. Furthermore, while these are complex cases often spread over multiple jurisdictions over several years, for the purposes of this paper only basic summaries of these cases are provided. The reader is invited to consult the source material for further information.

For ease of understanding, the cases are described in chronological order and are also numbered to streamline the analysis.

1. The ‘Russian Laundromat’

After uncovering it in 2017 along with Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta, the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) gave the name the ‘Russian Laundromat’ to a large-scale money laundering scheme that ran between 2011 and 2014. It was estimated that at least US$20 billion but possibly as much as US$80 billion was laundered through the scheme (Harding 2017). Almost 95 per cent of these funds reportedly originated from Russia (Tofilat and Negruta 2019).

Under this scheme, many fictitious companies were set up, which were typically registered in London and fronted by Moldovan nationals. Invented loan defaults between these companies were authenticated by Moldovan judges, which enabled Russian companies to make ‘payments’ to a court-controlled account in Moldova, housed within a bank called Moldindconbank. These funds were then transferred to a Latvian bank, a step enabling the funds to be laundered in the EU market and then to other jurisdictions (Harding 2017). The money originated from accounts associated with at least 19 Russian banks and was eventually laundered to over 5,140 companies in 96 countries (OCCRP 2017a).

The perpetrators behind the scheme involved a complex network of Moldovan and Russian individuals and entities. In Moldova, up to 15 judges and many bank officials were implicated (Harding 2017). Additionally, the involvement of three politically linked figures has been alleged by some commentators (Tofilat and Negruta 2019; Necsutu 2024c):

- Veaceslav Platon, a former member of the Moldovan parliament and major stakeholder of Moldindconbank. Platon, a Russian and Moldovan citizen, was also linked to the aforementioned Grand Theft case, although he was later acquitted in 2021. In the same year, Platon fled Moldova to the UK (Necșuțu 2024c).

- Vladimir Plahotniuc, who was the head of the pro-European Democratic Party of Moldova, but as the richest person in Moldova at the time, was widely considered to be an oligarch with outsized political and media influence (Kozlovska and Osavoliuk 2017). He fled Moldova in 2019, reportedly to Turkey.

- Renato Usatii, then mayor of the city 0f Bălți and the leader of the pro-Russian Our Party. Usatii ran in the 2020 presidential election and as of 2024 reportedly remains in Moldova.

The existence of loopholes in national legislation enabled the scheme. Tofilat and Negruta (2019: 10) explain how a bill approved by the Moldovan parliament in 2011 obstructed the power of the national anti-money laundering authority to detect and block suspicious transactions. They also flag that the responsible oversight bodies failed to give any indication of suspicious money flows originating from Russia in their annual reports, which could be a sign of political interference (Tofilat and Negruta 2019: 8-9).

In terms of Russian complicit actors, the money laundered was sourced from a range of offences (Tofilat and Negruta 2019). The main beneficiaries of the scheme were Russian businessmen, some of whom held contracts with the Russian government, that wanted to shift their assets to offshore jurisdictions for tax evasion purposes (OCCRP 2017b). However, according to the investigation it also included individuals – for example, Sergey Magin – who Russian authorities alleged were involved in organised crime (OCCRP 2017a). Lastly, there has been speculation that some of the laundered money derived from the misappropriation of public funds (Tofilat and Negruta 2019); for example, there are allegations that two Russian millionaires, Boris Usherovich and Alexey Krapivin, laundered funds they had embezzled from their contracts with the state-owned Russian railways, including by bribing Russian public officials (PressWay 2024). The OCCRP (2017a) noted that one of the Russian banks in question, the Russian Land Bank, had links to Russian intelligence services as well as Vladimir Putin (his cousin acted as an executive board member of the bank). However, OCCRP (2017a) did not explicitly allege state involvement in the scheme.

Both Russian and Moldovan law enforcement authorities initially described each other as largely uncooperative in investigating the scheme (OCCRP 2017a), but both have since independently pursued suspects. Between 2019 and 2024, the Russian interior ministry publicly accused Platon, Plahotniuc and Usatii on suspicion of money laundering through Russian banks and called for their extradition to face trial (OCCRP 2019; IPN 2024). Platon denied he was involved in any illegal activity (IPN 2019) although he was later handed a 20-year prison sentence by a Moscow court in a case tried in abstentia (Străjescu 2023). Both Plathotniuc and Usatii maintained their innocence and said the accusations were politically motivated (Barberá 2020; TASS 2019). In terms of the Russian businessmen who benefited from the scheme, the response of Russian authorities appears to be more nuanced. For example, as of 2024, Russian law enforcement agencies were targeting Usherovich who had relocated to the UK, but not Krapivin, who sources reported had reportedly regained favour with the Kremlin (PressWay 2024).

2. Igor Dodon

Igor Dodon served as the president of Moldova from 2016 to 2020 and is currently the leader of the Party of Socialists of the Republic of Moldova (PSRM), which has been associated with pro-Russian policies. Dodon himself has been alleged to have links with Russia, both political in nature and in pursuit of private interests.

Dodon has been extensively linked with the Russian oligarch Igor Chaika (or Chayka), the son of Yury Chaika, who served as Russia’s minister of justice from 1999 to 2006 and subsequently as prosecutor-general of Russia from 2006 to 2020 (Publika Md. 2019). Between 2017 and 2019, Chaika established two Russian companies – a construction company called Archplay Development and a waste disposal company called Industrial Ecological – in co-ownership with Alexander Dodon, the brother of Igor Dodon (Free Russia Forum n.d.).

Chaika has also intermittently acted as the representative in Moldova for Delovaya Rossiya (Business Russia), a Kremlin-backed non-profit organisation promoting Russian small and medium enterprises, and helped establish the Moldova-Russia Business Union, chaired by Igor Dodon, with the ostensible aim of promoting trade ties (Publika Md. 2019; Belton 2022). The deputy chair of the union, Vadim Yurcenko, previously occupied high-level positions at Russian state-owned companies such as the defence conglomerate Rostoc (Necșuțu 2022).

In 2022, the investigative journalism organisation RISE Moldova, in partnership with the Russia Dossier Center, uncovered six bank transfers made from a bank account linked to Delovaya Rossiya to the Russia-Moldovan Union, and found evidence that Chaika had made a large deposit on the same day to this bank account (Thorik and Kanev 2022). RISE could not identify how exactly this money was spent, but noted soon thereafter a decision was made to increase Dodon’s salary at the union (Thorik and Kanev 2022).

Dodon was also linked to other key political figures in Russia. In 2020, RISE and the Russian Dossier Center gained access to an encrypted application on a smartphone used by Dodon and according to both found evidence that, while he was president, Dodon had direct communication with officials associated with the Russian foreign intelligence service (SVR) (Ljubas 2020). Furthermore, RISE and the Russian Dossier Center claimed to have uncovered evidence that around the time Dodon had met with Gazprom Media (a media holding subsidiary company of the gas giant) in Moscow in 2015, Gazprom Media decided to award Moldovan broadcasting rights to a Moldovan company, Exclusiv Media, where Dodon’s wife worked (Ljubas 2020).

In 2019, a secretly recorded video was leaked in which Dodon appeared to indicate he received between US$700,000 and US$1 million per month from Moscow towards PSRM’s operating costs and that he was in discussions with the then Russian deputy prime minister Dmitry Kozak about the future of such funding (Necșuțu 2019).

In 2022, the US Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctioned Chaika, noting his relationship with Dodon and that in ‘exchange for the promise of Russian support in the election, [he] obtained backing for legislation preferred by the Kremlin, including a law to strip Moldova’s president of control of the country’s intelligence agency’ during the 2020 elections (US Embassy in Moldova 2022). Nevertheless, Dodon was defeated by the pro-Western Maia Sandu when he ran for re-election in November 2020.

In the wake of the 2022 Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Dodon issued statements interpreted as defending Russia’s actions (Thorik and Kanev 2022). He has also continued to stress how good relations with Russia and Gazprom can facilitate consistent and cheap energy supplies for Moldova (Locoman 2023).

In 2023, Chaika was sanctioned by the European Union for ‘serious financial misconduct, concerning public funds’ in Moldova, including ‘for funnelling money in support of the Russian federal security service (FSB) projects aimed at destabilising the Republic of Moldova’ (European Union 2023).

In 2022, Dodon was indicted by the anti-corruption prosecutor’s office on suspicion of receiving a bribe from Vladimir Plahotniuc in return for negotiating in his favour with Russia, especially with regard to his alleged role in the Russian Laundromat scheme (Locoman 2023). Dodon was released from house arrest in November 2022 pending further investigations (Locoman 2023). The Russian government said that, while it was monitoring the case against Dodon, it viewed it as an internal affair for Moldova (The Moscow Times 2022). Belton (2022) argues that as Dodon became more implicated in corruption scandals, his public popularity waned and Russia began to invest more political capital in Ilan Șor. Șor is a key figure in the following two cases.

3. Chișinău International Airport

Chișinău Airport was opened in 1960 and gained the status of an international airport in 1995. In 2013, the operation of the airport was granted for 49 years to the firm Avia Invest in a concession agreement (Erizanu 2023).

The agreement has been a controversial topic in Moldova for more than a decade. For some observers, the award process appears to have been valid (Hammond 2024). Others argue the procurement process was compromised and cite concerns that the executive government responsible for the decision had failed to fairly consider all bidders (Preașca 2023b), and that the contract contained conditions favourable to Avia Invest and its satellite companies at the expense of the state (Rață and Mihailovici 2015).

Another highlighted concern was that Avia Invest had been established rapidly before the contract was advertised under the ownership of Moldovan and Russian individuals and companies, many of whom made use of offshore financing arrangements and had ties to the Russian state (Rață and Mihailovici 2015). For example, one minority stakeholder in Avia Invest, Konstantin Basiuk, is currently a member of the Russian senate (the Federation Council) and was placed on the EU’s sanctions list in 2023 (Preașca 2023b).

The largest stakeholder in Avia Invest was Ilan Șor (alternatively Shor), an Israeli-born oligarch with Moldovan and Russian citizenship, the latter of which he reportedly acquired in 2024. Șor reportedly abused the management of the airport and awarded favourable contracts to other companies controlled by or linked to him; for example, the airline Air Moldova (Erizanu 2023; Rață and Mihailovici 2015). Șor and the other founders of Avia Invest were also suspected of inflating their capital, using loans from Russian companies and relying on guarantees from banks linked to Grand Theft case, in order to be considered eligible for the concession (Preașca 2023b).

Șor was implicated in the Grand Theft case, including for allegedly paying a US$250 million bribe to the former prime minister Vlad Filat (Sanduța 2017), and in 2017 he was handed a seven-year prison sentence (Sanduța 2017). Șor fled to Israel while under house arrest in 2019 and thereafter to Russia in 2023, the same year in which an appeals court in Moldova tried him again in absentia and increased his sentence (Necșuțu 2024b). Amid the domestic investigation against him, Belton (2022) cites evidence indicating that in 2019-2020 Russian intelligence (FSB) helped Șor transfer his controlling stake (more than 95% by that stage) in Avia Invest to Andrei Goncharenko, a Russian billionaire who acted as a CEO of a Gazprom subsidiary. However, Goncharenko stated shortly after that he had given up his stake as it was no longer a strategic business investment (Necșuțu 2020).

In 2019, the Moldovan parliament voted to launch a commission of inquiry into the awarding process, and in 2020 a decision was made to terminate the agreement, though the stated rationale was failure to fulfil the investment obligations under the concession rather than corruption (Străjescu 2024).

The termination was appealed by Avia Interest who argued it was politically motivated and amounted to expropriation by the Sandu government, but it was upheld by the Moldovan supreme court; in 2023, Avia Invest stated its intention to submit the case to the European Court of Human Rights (Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty 2023; Preașca 2023b).

In 2023, the anti-corruption prosecutor's office charged eight members of the executive government that had been responsible for approving the concession agreement, including former prime minister Iurie Leancă, for suspected corruption that caused public losses of US$21.8 million (Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty 2023). As of 2024, hearings were yet to start, but Leancă – currently the leader of the European People’s Party of Moldova, which campaigns for further integration into Europe – stated he could justify the decision to award the concession to Avia Invest in court (Străjescu 2024).

4. Allegations of illicit financing and vote buying against ȘOR Party

In conjunction with his business activities, Ilan Șor is active politically in Moldova. He was mayor of Orhei between 2015 and 2019, and in 2016 was elected as the president of the socio-political movement Equality, which thereafter was named the Șor Party.

The party has been widely described as taking pro-Russian positions and in recent years has repeatedly been the subject of allegations of electoral corruption and peddling foreign influence, often with links to Russian actors. For example, the Washington Post found evidence that Russian intelligence services (the FSB) facilitated the deployment of Russian political strategists to advise the party (Belton 2022).

In 2022, Moldovan authorities opened an investigation into the Șor party on suspicion of having received undisclosed and illicit funds, from Șor himself living in exile and from other Russian sources (Radio Moldova 2023). However, the party denied being financed by Russia (Zămosteanu et al. 2023).

In the same year, the Șor party was accused of paying and bussing citizens to stage protests in Chișinău against the Sandu government (Ziarul de Gardă 2022). The party denied the allegations and said the arrests constituted a suppression of what were legitimate protests about the government’s crackdown on the party (Belton 2022). In 2022, OFAC sanctioned Șor for electoral interference in Moldova ‘on behalf of, or for the benefit of, directly or indirectly, the government of the Russian Federation’ (US Embassy in Moldova 2022).

The party continues to be popular in the Orhei area, but one of its strongest bases of support is in Gagauzia. Jensen and Rupert (2024) argue that in recent years the Kremlin has concentrated its geopolitical interests on Gagauzia and backing the Șor Party’s efforts there. In 2023, the party won regional elections in Gagauzia under the leadership of Evghenia Guțul. Nevertheless, some observers have argued that her victory was achieved with the aid of various malpractices, including organised bussing for voters (Erizanu 2023).

These alleged offences culminated in Moldova’s constitutional court banning the Șor party in June 2023 (International Crisis Group 2024). However, over the next year Șor established the Victory Bloc, widely considered to be a group of aligned pro-Russian parties to circumvent the ban (Nilsson-Julien 2024; Necșuțu 2024b).

In 2024, Șor, Guțul and the party became associated with fresh allegations of electoral interference, this time in relation to the referendum on the EU accession constitutional amendment and the presidential election in October.

Ahead of these elections, in what many commentators characterised as blatant vote buying, the state-owned Russian bank Promsvyazbank said it would provide pensioners and public-sector employees in Gagauzia with payment cards which they could use to withdraw monthly payments of up to US$100 (International Crisis Group 2024). The deal – reportedly sealed following a trip by Guțul to Moscow – was uncovered by Moldovan authorities in September; the national police said it had reason to believe ‘more than 130,000 Moldovans had been bribed by a Russia-managed network to vote against the referendum and in favour of Russia-friendly candidates’ (EurActiv 2024b).

An investigation by RISE Moldova uncovered evidence suggesting Șor had created five Russia-based companies specialising in financial services to funnel up to US$15 million to Promsvyazbank to finance these payments to voters (Sanduța 2024). Guțul has claimed that the allegations are fabricated (EurActiv 2024a), while Șor rejected the allegations of bribery and countered that the PAS party accepted funding from Western non-governmental organisations (EurActiv 2024b)

De Vocea Basarabiei (2024) reported about similar payments being made to priests of the Metropolis of Chișinău and All Moldova (also known as the Moldovan Orthodox Church) who are politically influential, especially in Gagauzia. The party has also been accused of more indirect forms of vote buying involving the abuse of state resources by, for example, offering residents of Orhei compensation for their water bills immediately prior to the election (Canal5 2024).

In the aftermath of the revelations, Moldovan authorities initiated an investigation into electoral interference as well as introduced the offence of ‘passive electoral corruption’ to its criminal code, stating that voters who accepted payments or other undue benefits ahead of the 2024 elections would be fined (Rotari 2024).

Analysis of cases

This section analyses the four cases described above to better understand the nature of Russia-linked corruption in Moldova.

It does this by posing three questions:

- Does the case involve clear act(s) of corruption?

- Are there links between the identified Russian actor and the Russian state?

- Are there links between the corrupt acts and a Russian geopolitical objective?

These questions can help shed light on whether, where Russian entities are implicated in an act of corruption perpetrated in Moldova, the motivation is primarily private gain or if it serves geopolitical goals of the Russian state and thus resembles strategic corruption.

Nevertheless, it is not possible to provide conclusive answers to these questions for these four cases, given the incomplete evidence. Therefore, the analysis should be regarded as exploratory in nature. Furthermore, the small number of cases means these they do not necessarily give a good insight into the scaleof Russian involvement in corrupt acts in Moldova, and there may be less documented but more widespread practices at play.

(i) Does the case involve clear act(s) of corruption?

One aspect of answering this question is evidentiary. In none of the four cases has there been a clear admission of guilt from the accused parties (although there have been in absentia convictions); indeed, as seen in case #4, some actively deny the accusations and argue that the allegations of corruption have been weaponised by the current Sandu-led government in Chișinău.

Furthermore, these are largely allegations of high-level corruption, manifestations of which – for example, undue influence and exchange of favours – can by their nature be difficult to detect. Nevertheless, in the absence of conclusive evidence, the presence of anomalies or red flags may be indicative of corrupt practices.

Another aspect of this question is definitional, namely whether or not the accused act amounts to corruption in line, for example, with Transparency International’s definition of corruption as the ‘abuse of entrusted power for private gain’. Several manifestations of external foreign interference, that could be as equally as destabilising as strategic corruption, may not fit under this definition (see Box 1).

Box 1: Russia-sponsored disinformation in Moldova

Several commentators have posited a link between Russian strategic corruption and disinformation. O’Kelley (2024) argues that corruption in the form of media capture can facilitate the spread of disinformation.

Several leading media outlets and television channels in Moldova are owned by Igor Chaika and other Russian companies (Sittig and Fabijanić 2020; TVRMoldova n.d.). They are said to broadcast pro-Russian content as well as support for the Șor Party (Belton 2022).

There have been allegations that these outlets spread disinformation. This includes content of an explicitly political nature – for example, through deepfake videos depicting Maia Sandu announcing her resignation and endorsing the Șor Party candidate (Wilson 2023) – but also other forms of messaging, including anti-LGBTQ content (Sandu 2024) and what has been characterised as gendered attacks against Sandu (WiIfore 2024). Disinformation is also disseminated by other, less formal, sources, such as a US sanctioned Russian individual linked to foreign intelligence for operating a ‘troll factory’ that spread disinformation in Moldova (US Embassy in Moldova 2022)

In the wake of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, several channels and websites were blocked or had their licences suspended by authorities in Chișinău with the stated purpose of preventing the circulation of disinformation (Erizanu 2023). This move has been controversial and reportedly intensified polarisation among the Moldovan public; in the Gagauz autonomous region, media distributors have continued broadcasting channels in violation of the bans, reportedly with the complicity of regional government officials (Cheptanaru 2023).

While certain Russian actors have a significant stake in the Moldovan media landscape which they use to spread disinformation, no concrete allegations of corrupt practices facilitating their acquisition of this stake were identified in the desk research carried out for this Helpdesk Answer.

In case #1, there were allegations that Moldovan public officials (judges, oversight institutions) engaged in corruption to facilitate the money laundering scheme; indeed, some judges have been penalised in Moldova for their involvement. There were also allegations of corruption taking place in Russia in the form of misappropriation of state funds.

The events of case #2 speak to several potential forms of corruption. These relate chiefly to illicit political finance as PSRM reportedly received undisclosed funds from the Russian state. Foreign entities providing funding to a political party in another country may constitute corruption but not always (Kupferschmidt 2009), and this may hinge on whether or not the transfers were made legally (Bak 2021: 6). In Moldova, donations from foreign entities to contesting parties are not banned per se, but they must be declared.

There are also suggestions of potential conflicts of interest and undue influence. Dodon had both familial and personal links to Russian state and non-state companies, which could have incentivised him to treat them favourably, especially when he was serving as president.

The presence of corruption in case #3 is perhaps the most unclear given that it currently remains unknown what factors drove the executive government to award the concession agreement to Avia Interest, although some commentators have highlighted red flags in the award process that could indicate corrupt practices.

In case #4, in addition to similar allegations of illicit financing (of the Șor Party), there are claims of electoral malpractices. For example, vote buying and the abuse of state resources can constitute forms of what has been termed electoral corruption (Transparency International 2014).

(ii) Are there links between the identified Russian actor and the Russian state?

As Lang (2024) explained, the concept of strategic corruption presumes at least some level of involvement of a state principal. In some cases, there may be direct contact between the foreign state and the domestic public official; for example, via state-owned companies like Gazprom but also the suggested links between Moldovan politicians and Russian intelligence. However, more commonly, this is achieved through a non-state intermediary, such as a business figure.

While many Russian private actors, especially oligarchs (Rupert 2023), have developed deep ties with the Putin administration, the functioning of this business-politics nexus in Russia can be highly nuanced. These relations may not be static and such actors can move in and out of the Kremlin’s favour. Some non-state actors may attempt to curry favour with the Kremlin at the same time as advancing their own interests, but with limited central coordination or direction from Moscow.

Lastly, these kinds of cases typically involve complex networks of entities spanning multiple jurisdictions. It is important to distinguish between where the role of any identified Russian actor is incidental or instrumental.

For case #1, since most of the laundered money was allegedly sourced from Russian businesspeople through Russian banks, it can be safely said that they acted as a key driver. While there are some suggested links between complicit Russian actors in the scheme and the Russian state, case #1 is the only case in which Russian authorities appear to be seeking the prosecution of some of the (Moldovan and Russian) figures accused.

In case #2, the links between the various figures and the Russian state appear to be substantiated. The allegations implicate Russian state-owned bodies such as Delovaya Rossiya and Gazprom as well as Russian intelligence services; furthermore, Igor Chaika has familial ties to the Russian government.

In case #3, many of the main stakeholders of Avia Interest and thus beneficiaries of the concession agreement were Russian. Links to the state appear evidenced given the close ties between some of the main beneficiaries, such as Șor and Goncharenko and Kremlin, and minority stakeholders such as Basiuk, who is a member of the Russian senate.

Similarly for case #4, the alleged role of the Promsvyazbank implicates the Russian state, notwithstanding the views of many commentators that the Kremlin actively supports the Șor party.

(iii) Are there links between the alleged corrupt acts and a Russian geopolitical objective?

Whether or not the act of corruption occurred in pursuit of a geopolitical interest is perhaps the most difficult question to answer. As discussed above, while Russian geopolitical goals in Moldova may not be clearly stated, they appear to be quite diffuse and concern many key strategic sectors. The fact that a case takes place in or adjacent to such sectors may not in itself be evidence of a geopolitical motive. Therefore, ascribing a potential geopolitical objective to an act of corruption necessitates a degree of conjecture.

In case #1, a clear objective is not obvious. The Kremlin has publicly condemned and charged some of the accused individuals. Even if there was some degree of collusion by Russian officials, it is difficult to see how the scheme and what it entailed (for example, loss of tax revenue) was in the interest of the Russian state. Notably, the Moldovan political figures implicated represent both pro-European and pro-Russian positions.

In case #2, the alleged attempt to capture Dodon may indicate a geopolitical motive. For example, Dodon spoke in defence of Russia in the aftermath of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. However, Dodon and the PSRM party openly espouse pro-Russian policies, so it may be difficult to attribute their actions to any single act of corruption. Dodon was also involved in an organisation promoting Russian business interests and it possible that he received funds and benefits with the expectation that he advance such interests in Moldova.

As alluded to, it is unclear to what extent corruption played a role in the awarding of Chișinău International Airport concession agreement. That being said, certain commentators have highlighted that Russian influence over the airport could have been a factor. For example, Socor (2013) has argued it could give Russian intelligence services access to information on persons of interest travelling through the airport, although the author of this Helpdesk Answer was unable to find any evidence that this threat materialised.

In case #4, Russian state complicity (via the Promsvyazbank) in the Șor Party’s vote buying scheme would align what many observers have characterised as the Kremlin’s objective to obstruct pro-European political sentiment in Moldova, including its reported prioritisation of Gaguazia.

In sum, of the four cases, cases #2 and #4 likely amount to the clearest cases of strategic corruption, although further evidence would be needed to substantiate this. This is perhaps unsurprising given the definition of strategic corruption and the number of conditions that a case needs to meet to quality as strategic, not to mention the evidentiary burden each of these carries. Case #1 might better be considered an example corruption in which Russian actors obtained an economic benefit, while case#3 displays potential red flags for corruption, the connections of which to geopolitical objectives are unclear.

While it may not be possible to determine the bearing that strategic corruption and other forms of Russia-linked corruption has on the political stability of Moldova (which also faces corruption emanating from domestic and other foreign actors), they appear to pose a significant threat to the stated desire of the current government to integrate further with the European Union. Given the current geopolitical climate and Moldova’s position at a crossroads where Western powers and Russia vie for influence, the threat of strategic corruption and other forms of Russia-linked corruption are arguably likely to persist and undermine Moldova’s integration efforts, thus necessitating robust countermeasures.

Anti-corruption responses

This section outlines a selection of domestic anti-corruption measures that have been proposed by experts and commentators with regard to Moldova, prioritising those are most relevant for addressing the type of threats identified in the previous sections.

For the most part, these measures have the potential to be effective regardless of whether the motives behind the act of corruption are in furtherance of geopolitical goals or of a chiefly economic nature. Dolan (2024) makes the case that strategic corruption does not require a distinctive policy response to non-strategic forms of corruption, given that both arise from similar governance vulnerabilities. He therefore advocates for a ‘implementation of existing integrity policies in public- and private-sector institutions’.

In relation to Moldova, Samorukov (2024) has warned that the attention given to the ‘fight against Russian meddling also drives the domestic debate away from social and anti-corruption issues, though the emphasis on the latter was the key reason behind Sandu and PAS’s past electoral victories’.

While it is self-evident that the Russian government would need to undertake measures to fully extinguish the risks of corruption linked to Russian actors, this section focuses on measures that Moldova can take domestically, without having to rely on cooperation from the Kremlin, something which may not be forthcoming amid the present political tensions.

There are many domestic measures that can contribute to a robust response to the type of risk posed by Russia-linked corruption (or indeed other manifestations of undesirable foreign influence). These could include, for instance, reducing energy dependence or bolstering the capacity of Moldovan intelligence services. This section limits itself to policy responses that are directly related to anti-corruption measures. Nonetheless, analysts argue that such anti-corruption measures can work most effectively when developed in tandem with enhanced Moldovan security and intelligence efforts to prevent external meddling (International Crisis Group 2024).

In February 2024, the Moldovan parliament adopted the national integrity and anti-corruption programme (2024-2028) and its action plan for the implementation of the national integrity and anti-corruption programme.

Additionally, Moldova’s anti-corruption frameworks are subject to several ongoing assessment processes that have identified relevant shortcomings. In this section, insights from the following three processes are considered in particular:6f710dc4c32e

- Since Moldova entered the EU accession process in 2022, the European Commission has identified nine steps for it to fulfil, some of which pertain to anti-corruption reforms. The most recent assessment was published in October 2024 (European Commission 2024).

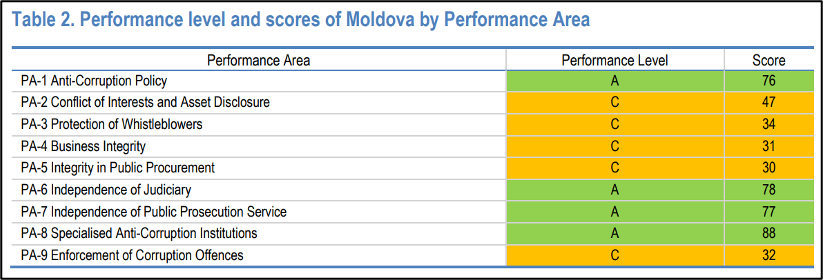

- Moldova participates in the OECD’s periodic monitoring of anti-corruption reforms, which assesses its frameworks in line with OECD standards; Moldova was assessed most recently under the fifth round of monitoring in 2024 (see Figure 3) (OECD 2024).

- The Independent Anti-Corruption Advisory Committee (CCIA) was established in 2021 by a presidential decree issued by Maia Sandu. The CCIA is a joint independent international and national body which has issued recommendations against which it tracks progress. This includes 42 recommendations pertaining to money laundering risks (CCIA 2023a) and 52 recommendations pertaining to political finance (CCIA 2023b).

Figure 3: OECD 2024: Fifth round of monitoring of anti-corruption reforms in Moldova

Sourced from OECD 2024: 12

Political finance controls

As cases #2 and #4 indicate, one of the most pressing Russia-related corruption risks concerns the illicit financing of Moldovan political parties and electoral campaigns, to enrich and influence domestic politicians and to buy votes. Additionally, there may be emerging threats; Jensen and Rupert (2024) argue the Moldovan authorities need to develop strategies to counter novel Russian illicit finance methods, such as the use of digital credit and cryptocurrencies.

Observers have identified gaps in Moldova’s efforts to ensure political finance integrity. The CCIA (2023b) highlights that, under Moldovan national law, bodies established as foundations do not have the same disclosure laws as political parties, which can lead political actors to launder funds through foundations to finance their political activities. Furthermore, Moldova currently has no comprehensive law regulating lobbying (European Commission 2023). Wilson (2023) argues that aside from legislative reform, more effective auditing of financing is needed in practice. Similarly, the CCIA (2023b) states that underreported expenditures are a repeated issue in Moldovan elections.

In terms of protecting against external threats to the integrity of political finance, Bak (2021:16) explains that the general practice is to ensure third parties with political aims and activities are subject to the same campaign financing rules as domestic political actors, but notes that in some jurisdictions foreign donations to political actors are banned entirely.

The CCIA issued 52 recommendations (2023b) aimed at the central electoral commission of Moldova and other stakeholders on how to address political finance concerns, including enhanced rules around disclosure, oversight and state funding to parties. In its 2024 progress review, the CCIA noted encouraging implementation levels, finding that 16 recommendations had been fully implemented (including one on strengthening the role of Moldovan intelligence services to detect illicit financing) and ten had been partially implemented, but that 26 recommendations remained unimplemented (CCIA 2024).

Of these 26, some of the most relevant for the purposes of external threats to political finance include (2023b):

- ‘The central electoral commission should create mechanisms for verification of donors living abroad and the value of their donations’

- ‘Parliament should amend the electoral code and the Law on Political Parties to regulate third party financing of political parties and electoral campaigns, to prevent undisclosed financial support, following a comprehensive process of consultations with civil society, so that the legal provisions do not infringe on freedom of association’

- ‘Parliament should amend the electoral code to require third parties willing to engage in electoral campaigns to register in advance with the central electoral commission and subject them to the same campaign finance regulations as electoral contestants’

- ‘Parliament should increase sanctions for non-compliance with the disclosure requirements, in order to strengthen the transparency of financing of the political advertisements’

- ‘The central electoral commission should strengthen the mechanisms for controlling companies rewarded with public contracts after elections to avoid conflict of interest and ensure independence of political parties from undue influence’

- ‘Parliament should consider the amendments to the criminal code, according to which illegal foreign funding of political parties and electoral contestants and illegal foreign funding intended to influence results of elections in Moldova would be sanctioned in a form of a criminal offence’

The importance of respecting freedom of association and other safeguards when developing legislation has been highlighted by the European Commission (2024). In 2024, Moldova’s constitutional court ruled as unconstitutional legislation introduced to prevent individuals associated with banned political parties (widely considered to be targeted at the Șor party) from running in elections independently or for other parties (Tanas 2024; European Commission 2024). In this vein, the commission recommended that Moldova should continue to engage with the Venice Commission and the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights on future changes to the electoral code.

Criminal justice and international cooperation

While a handful of key individuals – of both Russian and Moldovan origin – have been instrumental in perpetrating alleged acts of corruption in the four cases analysed in this paper, most have not been tried in a judicial process to test their guilt, even if they have been charged. Not only does it imply such figures may be able to continue to play an active (and potentially destabilising) role in Moldovan political life but means that other actors may not be deterred from committing similar transgressions.

In 2023, the European Commission expressed regret that ‘there was no significant progress in the prosecution of high-profile corruption cases and long-standing criminal cases’ in Moldova (European Commission 2023). The commission (2023: 5) also highlighted long-standing issues regarding the effectiveness of the criminal justice system, noting low clearance rates and the large backlog of cases.

However, many of the individuals implicated in high-level corruption cases have fled Moldova and are residing in Russia or other countries. The unwillingness of such countries to extradite these people to face trial in Moldova impedes justice. Notably, Moldova has long sought Șor's extradition, first from Israel and thereafter from Russia, to date unsuccessfully (Tanas 2024). In such cases, it may nevertheless be able to prosecute fugitives in absentia, which was facilitated by legislation introduced in 2022 (European Commission 2023). Furthermore, the government has committed to strengthen its mechanisms for the confiscation of assets deriving from criminal acts, including corruption (Președintele Republicii Moldova 2023).

In some cases, the unwillingness of other countries to extradite suspects may be related not to a lack of political will but due to procedural or human rights concerns. For example, a court in the UK refused to extradite a Moldovan national due to a lack of guarantees about the safety of its detention facilities (Zdg 2021); indeed, most of the rulings made by the European Court of Human Rights against Moldova relate to what have been deemed as inhumane detention conditions (European Commission 2023).

Furthermore, third countries may seek assurances that extradited individuals will receive a fair trial free from political interference. In the past decade, observers have repeatedly raised concerns about the independence of Moldova’s judiciary, members of which have been implicated in repeated corruption scandals. Nevertheless, in its recent assessment, the OECD (2024) acknowledged improvements and scored Moldova high for the independence of its judiciary, public prosecutor and anti-corruption authority.

Finally, bottlenecks to extradition may be attributed to the absence of necessary bilateral treaties or flawed mutual legal assistance (MLA) processes. Between 2020 and 2021, Moldovan authorities reportedly filed 40 MLA requests to 18 countries with regards the aforementioned Grand Theft case, but to date only 10 requests have been executed by partner countries (OECD 2024). These bottlenecks may be overcome through enhanced diplomatic endeavours and engagement of Moldovan authorities in international fora dedicated to international cooperation in criminal matters. For example, as of 2023, Moldova was engaged in 13 joint investigation teams6a7203631274 with other countries through with EuroJust (n.d.).

Conflict of interest and undue influence regulations

The cases above also speak to the risk of conflicts of interests between Moldovan political actors and their business interests linked to Russia. Furthermore, they indicate the potential for undue influence by Russian actors and certain business figures – such as, Russian-friendly oligarchs – over political (and judicial) decision-making, especially where they maintain a controlling stake in key sectors like energy.

As a measure against conflicts of interest, Wilson (2023) recommends that Moldova establish a robust asset declaration system to determine the wealth and income of political figures. Moldova’s system currently dates from a legislation enacted in 2016 and is overseen by the national integrity authority (NIA). However, the OECD 5th round monitoring assessment identified conflicts of interest and asset disclosure (as well as the related topic of the public procurement integrity) as persistent shortcomings (see Figure 3). It noted that, while Moldova has established a national agency for the resolution of complaints to address complaints related to public procurement, conflicts of interest violations were not sanctioned effectively in either law or practice (OECD 2024).

In its 2024 assessment, the European Commission commended Moldova for initiating the process to amend the asset declaration methodology, but recommended certain improvements, including (European Commission 2024):

- Moldova should ensure that people holding top executive functions step aside from the decision-making process in the event of a conflict of interest.

- Moldova should publish registers of declarations of conflicts of interest to make the integrity checks more efficient and reduce the number of acts invalidated in courts.

- Moldova should review the rules for public servants on declaring and accepting gifts (European Commission 2024).

- Parliament should implement a mandatory obligation for NIA to do ex officio checks (i.e. investigations triggered by the NIA itself).

In its efforts against undue influence, the government has been pursuing a strategic approach to ‘de-oligarchisation’ (European Commission 2023). This includes the adoption of an action plan that sets out planned measures as well as the development of a draft law on limiting excessive economic and political influence in public life.

This includes strengthening the capacity of Moldova’s competition council to proactively investigate and sanction market abuses such as cartel and monopoly behaviour, as well as specific measures in strategic sectors; for example, parliament has adopted amendments to the audiovisual media services code to contain outsized influence by oligarchs in the media sector (European Commission 2023; Președintele Republicii Moldova 2023).

External and independent oversight bodies can also address conflict of interest and undue influence risks by, for example, auditing a significant procurement process and decision. The court of accounts serves as Moldova’s supreme audit institution; the European Commission (2024) noted improvements in the court’s institutional quality, but stress more steps were needed to give it full organisational, functional and financial independence.

The private sector also has a responsibility to discourage, detect and report any suspicion of conflict of interest and other offences. Moldova’s national anti-corruption centre (NAC) engages with the private sector extensively on anti-corruption and has launched an award programme for businesses displaying high business integrity standards.

Transparency measures

Another aspect common to all four cases above is the presence of complex networks in which Moldovan and Russian individuals have hidden behind companies, bank accounts, foundations and other structures.

In this regard, Moldova can enhance its efforts in collecting and making publicly available beneficial ownership information to facilitate better detection and evidence gathering of corruption linked to Russian actors, to identify where politically exposed persons and domestic public officials have a stake in Russian companies (or are linked to individuals that do). This can be done by law enforcement authorities and investigative journalists whose contribution has been instrumental thus far in uncovering cases. For example, in case#4, RISE Moldova relied on beneficial ownership information to connect Șor to Promsvyazbank.

Under current legislation, companies registered in Moldova are required to disclose information about their beneficial owners, which is accessible free of charge to the public through a website (OECD 2024). However, under its fifth round of monitoring of anti-corruption reforms, the OECD noted some shortcomings with the system, including that ‘no effective sanctions are in place for the failure to provide beneficial ownership information or provision of false information, and enforcement appears weak’ (OECD 2024). Weak enforcement may conceivably incentivise Russia-linked actors not to submit beneficial ownership information, which could mean potential leads go undetected.

Furthermore, the CCIA (2023a) recommended that the national bank of Moldova disclose and make public easily accessible information on ultimate beneficial owners of the commercial banks. This may be especially relevant for Russia-linked corruption given the prominent role of commercial banks in the cases described above. Greater transparency around ownership can enable Moldovan banks and other financial institutions to more effectively fulfil customer due diligence checks.

Protecting civil society and media

Civil society and independent media organisations have played an important role in drawing awareness to Russia-linked corruption in Moldova. Indeed, organisations like RISE Moldova were the driving force in uncovering some of the primary cases. The CCIA (2023b: 66) argues that the role of independent media, especially investigative journalists, is all the more important given that many mainstream media outlets are linked to or even controlled by complicit figures and therefore may be biased in their coverage of such issues or even perpetuate disinformation. Civil society organisations can also act as an important source of proposals for policies against external interference, as well as mobilise against electoral malpractice (CEPPS 2024:4).

This includes domestic organisations, but also external ones, perhaps especially ones from countries with similar exposure to corruption linked to Russia, such as Georgia and Ukraine. Their shared experiences in addressing and countering this threat could form the basis of impactful exchanges with Moldovan organisations.

Furthermore, Transparency International Defence & Security (2019: 2) highlights that it is important such organisations are protected to enable them to expose the use of corruption by other states. RISE Moldova has faced the threat of defamation lawsuits from the PSRM for its reporting on Russian links to corruption (CCIA 2023b: 66). The European Commission (2023) found that while journalists can work without state interference in Moldova, such interference often exists in Gagauzia. Furthermore, it noted insufficient measures had been taken to protect journalists against intimidation (European Commission 2024). The commission found an enabling environment exists for civil society organisations in Moldova and commended the government’s efforts to facilitate their involvement in policy dialogue.

- The term oligarch is loosely defined. Considering Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine, Konończuk et al. (2017) note that, while there are differences as to how oligarchs emerged, what connects them is their use of their economic and financial resources to exert a major or dominant influence on a state and its policies.

- The reader is invited to consult other assessment material to supplement this overview; for example the fifth evaluation round report of Moldova adopted in 2023 by the Council of Europe's Group of States against Corruption (GRECO).

- EuroJust (n.d.) defines a joint investigation team as a ‘legal agreement between competent authorities of two or more states for the purpose of carrying out criminal investigations’.