Indonesian forests: A rich source of rents

Indonesia has some of the most extensive tropical forests in the world. These forests are home to biologically diverse flora and fauna and provide livelihoods for millions of Indonesians.6b3e9bc5b5fc According to the Indonesian Ministry of Environment and Forestry,2275df7a2afe the total ‘forest area’ (kawasan hutan) is 92,520,000 hectares, or nearly 50% of Indonesia’s land mass. More than half of the forest area is designated production forest (hutan produksi) that can be commercially used; the rest is protected forest (hutan lindung) and conservation forest (hutan konservasi), in almost equal shares. Each of these designations comes with further subcategories of use and with a plethora of different concessions and licences.

The forestry sector, including timber from production forests and palm oil plantations, is an important source of public revenue in Indonesia, but corruption has facilitated illegal logging and undermined sustainable allocation and use of land. According to Indonesia Corruption Watch (ICW), corruption in the natural resources sector has caused state losses estimated at IDR 6.03 trillion in 2019.40dde003ac16 IDR 5.9 trillion of losses stemmed from corruption related to four mining cases. This is more than the combined losses due to corruption in the banking, transportation, government, and electoral services sectors, the other four areas examined by ICW.de97ccd47005

The state’s historical role in natural resource extraction through ownership of land and use of state-owned enterprises, alongside its regulatory powers, has long generated opportunities for rent seeking and corruption.03f80ddb0c86 The decentralisation of power in the early 2000s, after the end of the Soeharto regime, included delegation of some authority to the governors of Indonesia’s 34 provinces and the regents of its more than 400 regencies to issue forest concessions. The bonanza and legal abuses that followed led the central government to try to rein in the excess. Among other things, authority to issue forestry licences was shifted to the provincial level by Law 9 of 2015 on regional government.c1057617073d A lack of clarity in spatial planning is challenging the implementation of a coherent forest policy to this day.cb42290167c1

Because of the socioeconomic and environmental importance of Indonesia’s forests, the Indonesian Corruption Eradication Commission (Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi, KPK) made a concerted effort to address forest-related corruption cases in the first decade of the agency’s existence. Up to the end of 2016, the KPK’s enforcement department had successfully prosecuted six forestry-related cases involving 30 defendants at court.

This study is a product of research collaboration between the U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre and the KPK that started in 2019 and has been supported by German International Cooperation (GIZ). The project started out as a pilot to explore the case files and verdicts of completed corruption cases related to the forestry sector. During a kick-off workshop in May 2019, it was agreed that a first study would examine the complete case files (berkas perkara) of convicted regent Tengku Azmun Jaafar in depth, using social network analysis.a5718f226c0f A second study, the present one, would focus on comparing the verdicts of the 30 defendants prosecuted to date.

The aim of this study is to explore the main patterns, commonalities, and differences in how the KPK and the courts have handled these cases. Considering the lack of published systematic comparative analysis of KPK cases, this is a contribution in itself. From this basic analysis we draw preliminary lessons for the KPK’s future enforcement and prevention strategy in the sector and also address the accessibility of case-related data and verdicts for further analysis.

The KPK: Its mandate, authorities, and policy engagement in the forestry sector

The KPK was established by Law 30 of 2002 with a broad mandate in corruption prevention and enforcement. The law empowers the KPK to investigate and prosecute cases that involve law enforcement personnel or public officials, that give rise to particular public concern, and/or that involve losses to the state of at least IDR 1 billion. Although it has both investigative and prosecutorial powers, the KPK does not have absolute jurisdiction over corruption cases, but shares these powers with the National Police and the Attorney General’s Office. It can, however, take over cases from the police or the Attorney General’s Office when there is lack of progress or another problem defined by law, and it can coordinate and supervise other agencies that control corruption.

Under its preventive mandate, the KPK works to raise public awareness, conducts research about corruption risks, issues recommendations on how to address these risks, and monitors implementation of the recommendations. The KPK’s Research and Development Directorate has conducted several sectoral studies with recommendations for policy makers. Their first forestry sector study, in 2010, examined the forest area planning and management system.d5a48e6145a3 The study identified weaknesses in regulatory, institutional, administrative, and human resource management aspects of that system under the then Ministry of Forestry (now merged with the Environment Ministry to form the Ministry of Environment and Forestry). It described challenges that had arisen in forest boundary demarcation processes and identified insufficient attention to future land use planning and change as a major problem.

Three years later, the poor scores of the then Ministry of Forestry in a KPK public sector integrity survey as well as the cases discussed in this paper prompted a further study of corruption risks in forestry licensing.9d31ca5fa2c3 This study found that most laws and regulations governing the forestry sector at the central, provincial, and regency levels in Indonesia are open to abuse, with 18 of 21 regulations reviewed considered to be particularly susceptible to corruption. For example, the administration of Commercial Forest Concession Licences (Izin Usaha Pemanfaatan Hasil Hutan Kayu) was identified as being susceptible to a range of corrupt practices, including state capture, petty corruption in the form of extortion by government officials, and influence peddling by external parties that have close relations with the authorities.

In 2014, the newly elected president of Indonesia, Joko Widodo, encouraged the KPK to calculate state losses in the forestry sector, to examine the systems that allow such losses to occur, and to coordinate efforts to fix these systems and improve revenue collection. In its subsequent study on preventing state losses in Indonesia’s forestry sector, the KPK07381053ba0b found that far more timber had actually been harvested than was captured in reports to the government. The study produced a quantitative model indicating that the actual amount of timber harvested from primary forests during 2003–2014 was between 630 million and 772 million cubic metres. However, the Ministry of Environment and Forestry statistics captured only around 19%–20% of total timber logged during the period of study. In monetary terms, the study established that the government collected USD 3.26 billion in taxes associated with timber harvesting between 2003 and 2014. The study’s quantitative model, however, calculates that the government should have collected revenues of between USD 9.73 and 12.25 billion for the same time period.

In a 2016 study on the oil palm commodity system, the KPK again highlights weak licensing, oversight, and control mechanisms, as well as extensive overlaps between areas covered by palm oil licences and other sector licences. By 2014, Indonesia’s oil palm sector was contributing around 6%–7% of gross domestic product, most of it as overseas exports. However, the KPK6127ad779745 established that commodity export levies were ineffective and tax collection ‘far from optimal.’

These findings, and the specific corruption cases discussed in this paper, motivated the KPK to support the government’s One Map Policy through the National Corruption Prevention Strategy. The One Map Policy is intended to increase transparency and accountability of natural resource management in Indonesia by creating conformity of spatial allocation and licensing as well as justice in the allocation of land and legal certainty to prevent land conflicts. Part of this policy is called Action to Accelerate the Determination of Forest Areas (Aksi Percepatan Penetapan Kawasan Hutan); it is a monumental effort by the Indonesian government to achieve legal certainty with respect to the status of forest areas. Legal certainty is expected to reduce overlapping permits and land use mismatches, which have both encouraged and concealed corruption. At the end of 2018, the determination of the legal status (perkembangan penetapan kawasan hutan) of 88,419418 hectares of forest area had been completed.ff99d8abe403

The National Corruption Prevention Strategy was launched jointly in 2018 by the KPK, the National Development Planning Agency (Bappenas), the Ministry of Home Affairs, the Ministry of Administrative and Bureaucratic Reform, and the Executive Office of the President. One of its 11 action points is to improve data governance and compliance in the extractive industries. The strategy’s secretariat is hosted by the KPK and supports the compilation, integration, and synchronisation of 13 of the overall 85 thematic maps under the Coordinating Ministry for Economic Affairs and the Geospatial Information Agency. The five focus provinces are Riau, Central Kalimantan, East Kalimantan, West Sulawesi, and Papua.

The KPK carefully monitors policies on forestry sector management and provides recommendations to national and local governments for policy change. The ongoing digitisation and increased surveillance of forest management under the One Map Policy is expected to sustainably reduce corruption. However, even when abuse is identified, enforcement and recovery of assets does not always happen. Prevention and enforcement efforts have been weakly integrated. The cases discussed in this paper were not ‘built’ in the sense of having been investigated by the KPK based on risk analysis done by the prevention department; rather, they were detected based upon reports from the public. Corrupt practices in the sector persist, and uptake of the KPK’s recommendations has been limited so far.

Aim and methodology of the study

The aim of our overall project was to explore what a systematic analysis of the KPK’s case files and verdicts can provide in terms of insights for the agency’s prosecution and prevention strategy. The plan for this U4 Issue was to explore how much analysis could be drawn from the verdicts alone. A very early draft of the paper was presented to the KPK in October 2019; the agency participated in background discussions and undertook a thorough review and fact-checking, but no formal interviews or systematic media analysis were conducted. The format of the verdicts imposed limitations on what was feasible within the scope of the project, as coding and processing of the data was extremely time-intensive.

Therefore, the scope of this paper is limited to a descriptive, statistical analysis of the commonalities and differences in the locus delicti and location of trial, and the types of criminal charges brought against the defendants. We also examine the defendants’ profiles, comment on the absence of corporations as defendants, and discuss the length of investigations, trials, and appeals. We compare the punishment (imprisonment, fines, restitutions, asset recovery) requested by KPK prosecutors with the sentences handed down by the courts.

Overall effectiveness in the criminal justice chain depends on all links of the chain: that is, effective investigation followed by effective prosecution, leading to strong cases decided by effective courts. Therefore, it would make sense to extend such analysis to the whole criminal justice process.0ce0190a50bc This study, however, only takes a retrospective glimpse of a limited set of data, namely the verdicts in a distinct set of cases. It cannot evaluate the effectiveness of the KPK as a whole, or the effectiveness of the anti-corruption courts or any other actors in the Indonesian criminal justice system. This would require a much more comprehensive approach.

What we did not do (yet) but could be done

An analysis of verdicts delivered by Indonesia’s court system faces two main limitations: access and format. While most verdicts are public documents, only since 2007 has the Supreme Court been publishing its verdicts online on a special website affiliated to the Supreme Court. The compilation is incomplete, containing only a few verdicts from the lower courts. Until very recently it could only be searched using the type of court/jurisdiction, the defendant’s name, the specific case number, and keywords.b22552959155 Shortly before this paper was published, the website structure was overhauled. While it now contains a much more elaborate search function, the verdicts on corruption cases are not yet complete, with many verdicts, particularly those from first instance and appeals courts, missing.

Another immediate limitation we faced when handed the verdicts of cases indicted by the KPK was that they were scans of the original documents, image files in PDF format. As images, they cannot be digitally searched. An OCR (optical character recognition) format would allow researchers to analyse, for example, to what degree court verdicts incorporate the prosecutors’ indictments verbatim in their reasoning, something that observers claim has happened frequently. Many of the verdicts are several hundred pages long; the huge size of the documents makes transferring the files and even scrolling through them quite tedious, not to mention that some of the pages are upside-down. The verdicts on the special website of the Supreme Court are, as of mid-2020, in a searchable format.

To put the 30 defendants’ verdicts into perspective, it would also be useful to apply the same kind of analysis to all KPK cases and see whether there have been particularities in the prosecution of forestry-related cases – although as we will later see, the main shortcomings (lack of corporate liability and restitution of damage) seem to characterise corruption cases across sectors. As the KPK shares jurisdiction over corruption cases with the Attorney General’s Office, the forestry sector cases prosecuted by the latter would provide a natural benchmark, provided the same data were made available.

To assess the efficiency and effectiveness of the investigation and prosecution process, and perhaps even compare it with that of the Attorney General’s Office, we would need more primary data from the law enforcement agencies, such as the timelines for investigation and prosecution, the costs of the cases, and the composition and size of the investigation and prosecution teams. Ideally, this would be complemented by systematic trial monitoring by trained external observers. Such information would allow us to assess compliance with due process and the rights of the defendants, as well as, importantly, the capacity of the prosecution and judiciary to rigorously unpack complex financial crimes and withstand political influence.4a3e9a9615af

There is an immense body of literature and programmes dedicated to evaluating judicial effectiveness.b5ab5b86cd0d In general, these studies attempt to measure efficiency, the ability to dispose cases in a timely manner without undue delays, and quality, the application of and compliance with legislation in proceedings and decision making. This information is considered in the context of the available capacity and levels of human, financial, and technical resources.

Often, independence and impartiality are integral aspects of a quality assessment, as indicated by the absence of improper influences on judicial and prosecutorial decisions and by trust in judges and prosecutors. Scholars who are particularly concerned with accountability and transparency may also review whether the judicial mandate has been carried out with sufficient levels of public access to information and public confidence.bb4182e877f6

Such analysis is, of course, only possible with the (timely) availability and accessibility of data sources, and it is thus most easily conducted in collaboration with the judicial system itself. This approach also has the advantage of a short feedback loop and increases the chances that findings and results will be followed up within the justice system. We note, however, that access and exchange even of non-confidential information within the KPK is currently not supported by an adequate, integrated knowledge infrastructure across the different departments.

The Indonesian court system and its verdicts

Judicial power in the Indonesian court system is divided between, on the one hand, the Constitutional Court, and on the other, the Supreme Court and the four branches below it: the general courts, the administrative courts, the religious courts, and the military courts. The first instance general courts are located in Indonesia’s regencies and municipalities, and the general appeal courts (high courts) are in the provincial capitals. Since 2011, special anti-corruption chambers are located at the district courts48cbf38ad844 and high courts in Indonesia’s 34 provincial capitals. Cassation appeals are heard by special anti-corruption judges at the Supreme Court in Jakarta.2a934da9267b

The Supreme Court can also conduct a case review (peninjauan kembali) if new evidence is found that justifies a new hearing, if a fact or situation established in one decision contradicts aspects of another case, or if an oversight or obvious mistake was made in the decision.25d2a232e83e Such a review took place in the case of businessman Kwee Cahyadi Kumala alias Swie Teng, who was involved in the West Java case discussed below. After his first instance sentence, rather than appealing, he requested and received a case review; as a result his sentence was reduced by half, from five years to 2.5 years, by the Supreme Court. The verdict does not make clear whether this was based on new evidence, a contradiction with other cases, or an obvious mistake in the first instance decision.

Indonesian criminal judgments typically contain the name of the court, the number of the ruling, biographical data and residence of the defendant, the time (if any) spent in in pre-trial detention, and the names of the individuals presenting the defence. In most judgments this is followed by the charges against the defendant; a list of the evidence, including in some cases summaries of witness accounts at court; the verdict, including the reasoning, though with varying depth in verdicts investigated here; and the sentence (prison time, fines, restitution if any, seized assets).

Summaries of the forestry sector cases indicted by the KPK

Between 2004 and 2016, the KPK brought corruption charges against more than 400 defendants, at least 30 of whom were indicted for corruption related to the forestry sector.b31e28383e8c While cases from the mining sector may also affect forestry – for example, the unlawful issuance of mining licences can lead to the destruction of forests – we have focused on the cases that involved unlawful issuance of forest sector licences. The modus operandi is generally the same: government officials and private companies collude in the illegal issuance of licences that violate existing rules and regulations, resulting in the logging of forests (of varying quality). Based on the verdicts examined here, it is not always clear who initiated the corrupt deals, but all of the involved parties benefited from them.

All cases resulted in guilty verdicts. The first case obtained a final verdict in 2008, and the last case in 2016. In 2017–2018, the KPK successfully pursued 202 additional defendants, but only one case related indirectly to the forestry sector: that of Nur Alam. This last case is not included in the comparative analysis of this paper as it is, strictly speaking, a mining case and was under review by the Supreme Court at the time of writing. It is briefly discussed in Box 1 below.

The KPK counts cases by defendant, even though corruption charges are seldom brought against only a single individual. The mostly large-scale cases the KPK deals with often reveal a sprawling corrupt network with multiple players and middlepersons. Not all the players get charged, but there are typically several cases, or several defendants in a bigger case, linked to the same corrupt network. Nevertheless, the defendants are dealt with and recorded at the KPK separately, often with different investigative teams and prosecutors. Among the 30 defendants, only three were dealt with in the same trial, namely Azwar Chesputra, Hilman Indra, and H. M. Fachri Andi Leluasa. All three were members of the House of Representatives (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat, DPR).

In the KPK’s annual reporting, cases are listed by defendant, and on its Anti-Corruption Clearing House website the case descriptions are also presented by defendant. Until recently (mid-2020), cases could only be searched by defendant or year and not by any other variable (e.g., type of offence or sector).

For this paper, we have grouped together those defendants who conspired in a corrupt exchange by entering into transactions with each other, either directly or through intermediaries. Because all the cases involved local government and there are only six in total, we refer to them by province, e.g., East Kalimantan. In the following case summaries, the defendants, their positions at the time of the crime, and their sentences are listed first, followed by a short account of the case. The information is largely drawn from the KPK’s Anti-Corruption Clearing House, which has case summaries on some of the defendants, and from news reports.

East Kalimantan

Year of offence: 2000

Year of final verdict for S. A. Fatah: 2007

- Suwarna Abdul Fatah, governor of East Kalimantan; 4 years prison

- Martias alias Pung Kian Hwa, president-director of PT Surya Dumai Industri; 1.5 years prison

- Uuh Aliyudin, head of East Kalimantan Provincial Office of Forestry and Plantations (Kepala Kantor Wilayah Departemen Kehutanan dan Perkebunan Provinsi Kalimantan Timur); 4 years prison

- Robian, head of Forestry Office of East Kalimantan (Kepala Dinas Kehutanan Provinsi Kalimantan Timur); 4 years prison

Suwarna Abdul Fatah, the governor of East Kalimantan Province, launched a project to build 1 million hectares of palm plantation at Paser Utara, Berau, East Kalimantan. As part of this project, he issued the recommendation that wood utilisation permits (Izin Pemanfaatan Kayu) for a forest area of more than 200,000 hectares be granted to 11 companies under the PT Surya Dumai Group owned by Martias alias Pung Kian Hwa. The governor ignored the proper process and orally ordered Robian, head of the Forestry Office of East Kalimantan, and Uuh Aliyudin, head of East Kalimantan Provincial Office of Forestry and Plantations, to issue wood utilisation permits even though those companies had not met all requirements for such a permit. Missing were the plantation boundary documentation, commercial forest concession (Izin Usaha Perkebunan), feasibility study for the plantation, and bank guarantee for volume-based tax on timber harvesting (Provisi Sumber Daya Hutan). Suwarna then gave the companies under the Surya Dumai Group the principal agreement for land development and wood utilisation (persetujuan prinsip pembukaan lana dan pemanfaatan kayu), an authority that he did not actually possess, as it resided with the then Department of Forestry.

In total, 697,260 cubic metres of timber was cut and sold. Only a very small part of the land was eventually used for palm plantation because the land was not fit for that purpose. According to an audit by the Financial Supervisory and Development Board (BPKP), total state loss was IDR 346,82 billion, based on standard pricing of the timber. The Supreme Court ordered the restitution (uang pengganti) of exactly this amount from Martias to the state.

Riau 1: Pelalawan and Siak regencies

Years of offence: 2001–2007

Year of final verdict for Rusli Zainal: 2014

- Rusli Zainal, governor of Riau (2003–2008, 2008–2013); 14 years prison

- Tengku Azmun Jaafar, regent of Pelalawan; 11 years prison

- Syuhada Tasman, former head of Forestry Office of Riau; 5 years prison

- Burhanuddin Husin, former head of Forestry Office of Riau (Kepala Dinas Kehutanan Provinsi Riau); 6 years prison

- Asral Rachman, former head of Forestry Office of Riau; 5 years prison

- Arwin AS, regent of Siak; 5 years prison

Tengku Azmun Jaafar, regent of Pelalawan in Riau Province, ordered consecutive heads of the Forestry Office of Riau2e3637969484 to issue Commercial Forest Concession Licences for Industrial Plantations (Izin Usaha Pemanfaatan Hasil Hutan Kayu Hutan Tanaman) to a number of privately owned companies. Some of these companies were set up by Jaafar himself or by his family members and/or staff.22d8d8adaca9 The land owned by all these companies contained high-density forest areas that did not meet the Ministry of Forestry’s standards for conversion. The companies were then sold with their permits to PT Riau Andalan Pulp and Paper, a subsidiary of Asia Pacific Resources International Holdings, and to PT Indah Kiat Pulp and Paper under the Sinar Mas Group.

Tengku Azmun Jaafar gained about IDR 12.2 billion from this scheme, while his brother Lukman131a3bceb460 gained IDR 8.25 billion, and Syuhada Tasman got IDR 800 million. Asral Rachman received benefits amounting to IDR 1.5 billion, originating not only from the Pelalawan case but also from the Siak case.

The KPK also prosecuted Arwin AS, head of Siak Regency, for abuse of his power, causing state loss in a similar scheme. Arwin AS ordered Asral Rachman, head of the Forestry Department of Siak Regency, to process the request from five companies to obtain Commercial Forest Concession Licences. Asral Rachman only checked the requested areas of two of the companies, PT Rimba Mandau Lestari and PT Bina Daya Bintara, to ascertain that they were in fact natural forest areas. He did not survey the other three companies: PT Balai Kayang Mandiri, PT Seraya Sumber Lestari, and PT National Timber and Forest Product. These companies bribed Arwin AS with IDR 850 million and Asral Rachman with IDR 894 million. According to the Anti Forest-Mafia Coalition (2012), the state suffered financial losses of more than IDR 301 billion from timber sold by these five companies. The governor of Riau, Rusli Zainal, took part in both schemes by approving the annual work permits for the companies that obtained the concessions. The KPK also prosecuted Rusli Zainal for his involvement in corruption as part of the National Sports Week project.

Riau 2: Bintan Regency

Year of offence: 2006

Year of final verdict for A. A. Nasution: 2009

- Al Amien Nasution, member of DPR; 8 years prison

- Azwar Chesputra, member of DPR; 5 years prison

- Hilman Indra, member of DPR; 5 years prison

- H. M. Fachri Andi Leluasa, member of DPR; 5 years prison

- Sarjan Tahir, member of DPR; 4.5 years prison

- Yusuf Erwin Faishal, member of DPR; 4.5 years prison

- Azirwan, Bintan Regency secretary; 2.5 years prison

- Chandra Antonio Tan, managing director of PT Chandratex Indo Artha; 3 years prison

In April 2008, the KPK arrested Al Amien Nasution, a member of the DPR, and Azirwan, Bintan Regency secretary, in a sting operation. Azirwan bribed Al Amien for the parliament’s approval421e713b8211 to convert protected forest at Bintan Island into the new capital of Bintan Regency. The investigation led to further acts of bribery of MPs from Commission IV of DPR. Sarjan Tahir, an MP from South Sumatra, agreed to support the government of South Sumatera Province in its bid to convert protected forest area into a port. Sarjan Tahir, Commission IV chairperson Yusuf Erwin Faishal, Azwar Chesputra, H. M. Fachri Andi Leluasa, Hilman Indra, and Al Amien Nasution all received bribes from Sofyan Rebuin,119b51301452 the director of Tanjung Api-Api Port Agency, South Sumatera, and Chandra Antonio Tan, director of PT Chandratex Indo Artha, as the investor of the Tanjung Api-Api port construction. PT Chandratex Indo Artha was also the contractor for construction of the road from Palembang to Tanjung Api-Api port.f6312ca07f33 In 2006 Chandra Tan promised to pay a total of IDR 5 billion to Sarjan Tahir and other MPs to get parliamentary approval for the conversion of protected forest at Tanjung Pantai Air Telang, Banyuasin Regency, South Sumatera, to be converted into the port area.

Central Sulawesi: Buol Regency

Years of offence: 1999–2012

Year of final verdict for A. A. Batalipu: 2013

- Amran Abdulah Batalipu, regent of Buol; 7.5 years prison

- Gondo Sudjono, operations manager of PT Hardaya Inti Plantations; 2.5 years prison

- Siti Hartati Murdaya, managing director of PT Hardaya Inti Plantations and PT Cipta Cakra Murdaya; 2.67 years prison

- Totok Lestiyo, director of PT Hardaya Inti Plantations; 2 years prison

- Yani Ansori, general manager supporting PT Hardaya Inti Plantations and head of Central Sulawesi office of PT Hardaya; 2.5 years prison

At the time of the offence, Siti Hartati Murdaya was a tycoon and a member of the Advisory Board (Dewan Pembina) of the Democratic Party (Partai Demokrat), the ruling political party founded by former President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono. As owner of PT Cipta Cakra Murdaya and the Berca Group, she had obtained a location permit for a 75,000-hectare area for a palm plantation in Buol Regency, Central Sulawesi Province, but she held the right of exploitation (hak guna usaha) for only 22,780 hectares. Siti Hartati Murdaya wanted to exploit another 33,083 hectares. But in 1999, the minister of agrarian reform issued a regulation limiting palm plantations to a maximum of 20,000 hectares per company in a province.

In fact, PT Cipta Cakra Murdaya had already used 4,500 hectares for palm plantation under its subsidiary, PT Sebuku Inti Plantation, and in 2011 Siti Hartati Murdaya belatedly submitted the documents to secure the right of exploitation for the 4,500 hectares that were being cultivated. By 2012, Amran Batalipu, the regent of Buol, had not yet issued the recommendation that would have made this possible. Between April and June 2012, Siti Hartati Murdaya invited Amran Batalipu to meet in Jakarta and promised to give him IDR 3 billion to issue the permits she wanted. These included not only the right of exploitation for PT Sebuku Inti Plantation, but also a plantation permit and right of exploitation for another of her companies, PT Hartati Inti Plantations, in order to avoid the 20,000-hectare limit on land ownership by a single company in a province. Siti Hartati Murdaya ordered her staff, including Totok Lestiyo, director of PT Hartati Inti Plantations, as well as Gondo Sudjono and Yani Ansori, to bribe Amran Batalipu with a total of IDR 3 billion. In July 2012, the KPK captured Totok Lestiyo, Yani Ansori, and Amran Batalipu in Buol as they were handing over the money.

West Java

Years of offence: 2009–2013

Year of final verdict for K. C. Kumala: 2016

- Rachmat Yasin, regent of Bogor; 5.5 years prison

- F. X. Yohan Yap alias Yohan, staff of PT Bukit Jonggol Asri; 5 years prison

- Kwee Cahyadi Kumala alias Swie Teng, president of PT Bukit Jonggol Asri and president-director of PT Sentul City; 2.5 years prison

- M. Zairin, head of Agriculture and Forestry Office of Bogor (Kepala Dinas Pertanian dan Kehutanan Bogor); 4 years prison

On 14 May 2014, the KPK captured F. X. Yohan Yap and M. Zairin in a sting operation. Yohan Yap was an employee of PT Bukit Jonggol Asri (PT BJA), a giant property developer, and M. Zairin was head of the Agriculture and Forestry Office of Bogor Regency (Kepala Dinas Pertanian dan Kehutanan Bogor). The KPK seized IDR 1.5 billion at the time as part of a total bribe of IDR 5 billion. Further investigation by the KPK revealed that the money came from the owner of PT BJA, Kwee Cahyadi Kumala, and was destined for the Bogor regent, Rachmat Yasin, to finance his campaign in the 2013 Bogor Regency election.

PT BJA bribed Rachmat Yasin to obtain a recommendation to convert a designated forest area (kawasan hutan) of 2,754 hectares in Bogor Regency into a housing development called Kota Satelit Jonggol City. The Ministry of Environment and Forestry at national level has the authority over land conversion, but to convert forest area a company must first obtain a recommendation from the head of the regency, in this case Bogor.

But Rachmat Yasin had already granted part of that particular forest area to PT Indocement Tunggal Prakarsa and PT Semindo Resources for the siting of a cement factory. F. X. Yohan Yap, an employee of PT BJA, delivered a first payment of IDR 1 billion and a second payment of IDR 2 billion as part of a total promised bribe of IDR 5 billion. After receiving the money from PT BJA, Rachmat Yasin ordered M. Zairin, head of the Agriculture and Forestry Office, to advance the recommendation for conversion to the minister of environment and forestry. Rachmat Yasin issued the recommendation even though he knew that the conversion would overlap with an existing mining concession (Izin Usaha Pertambangan).

Riau 3: Kuantan Singingi and Rokan Hilir regencies

Year of offence: 2014

Year of final verdict for Annas Maamun: 2016

- Annas Maamun, governor of Riau (2014–2019, but sent to prison in 2016); 7 years prison

- Rusli Zainal, governor of Riau (2003–2008, 2008–2013); 14 years prison (including for Pelalawan case described above)

- Gulat Medali Emas Manurung, head of Indonesian Oil Palm Farmers Association, Riau chapter; 3 years prison

- Edison Marudut Marsada Uli Siahaan, president of PT Citra Hokiana; 3 years prison

During his visit to Riau Province in August 2014, Minister of Forestry Zulkifli Hasan presented his policy on converting forest area to non-forest area. Seizing the opportunity, Gulat Manurung, head of the Indonesian Oil Palm Farmers Association’s Riau chapter, approached the governor of Riau, Annas Maamun, seeking to convert his palm tree plantation, which was still officially forest area, into a non-forest area. Gulat Manurung’s plantation was located in Kuantan Singingi Regency (1,188 hectares) and Rokan Hilir Regency (1,214 hectares), both within Riau Province but outside the areas proposed for conversion by Minister Zulkifli Hasan.

In Jakarta, Governor Annas Maamun requested a total of IDR 2.9 billion from Gulat Manurung and another businessman, Edison Marudut, to proceed with the conversion. Governor Annas wanted to share the money with the DPR to approve the forest conversion. In September 2014, the KPK captured Annas Maamun at his home in Jakarta after he received a bribery payment from Gulat Manurung and Edison Marudut.

Analysis of the cases

Locus delicti and place of trial

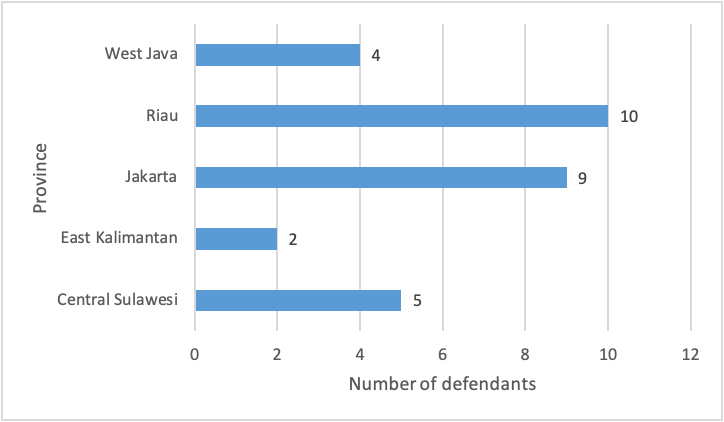

The crimes of the indicted cases took place in five provinces, Riau and Jakarta infamously leading with 10 and nine defendants respectively. National decision makers in Jakarta were also entangled in the cases in the other four provinces.

Figure 1: Locus delicti

Although crimes occurred in five provinces, most cases were adjudicated in Jakarta. Even after the decentralisation of the Anti-Corruption Court to district and high courts in provincial capitals in 2011, some cases were nevertheless heard at first and second instance in Jakarta. All defendants from Central Sulawesi were adjudicated in Jakarta, although their trials took place after the courts’ decentralisation.

According to the Indonesian Criminal Procedure Code (Law 8 of 1981), cases can be trialled at the court responsible for the area where the crime took place (locus delicti); or, alternatively, for efficiency reasons, where the majority of witnesses reside; or at another location for security reasons.ecfa852c7453 Witnesses, defendants (when on bail), investigators, prosecutors, and judges all can experience public pressure and threats that might be easier to avoid or control in another location. In Central Sulawesi, supporters of the regent of Buol, who was campaigning for a second term, quickly assembled when he was arrested at his residence. He had escaped a previous arrest by hitting the motorcycle of a KPK official with his car.cf0ce4d1d58d Due to the hostile atmosphere in the province, the trial was moved to Jakarta.

By comparison, after 2011 the cases from Riau and West Java were adjudicated at their local anti-corruption court. For example, F. X. Yohan Yap alias Yohan, M. Zairin, and Rachmat Yasin were adjudicated in Bandung, as their crimes took place in West Java. Only at cassation level was F. X. Yohan Yap heard in Jakarta. Edison Marudut and Annas Maamun, governor of Riau Province, were also adjudicated at the courts in Bandung because the actual bribe payment took place in West Java (though actually in South Jakarta). Gulat Manurung, who was also part of that transaction, was trialled in Jakarta.

Arwin AS, Burhanuddin Husin, Rusli Zainal, and Syuhada Tasman were adjudicated in Pekanbaru, the capital of Riau Province, before their cassation appeals were heard in Jakarta (where all cassation cases are heard).

Types of criminal charges

Law 31 of 1999 on corruption crimes, as amended by Law 20 of 2001, distinguishes 30 different types of corrupt crimes. The KPK0367b817357e has grouped them into seven categories:

- Abuse of power causing losses to the state

- Bribery

- Embezzlement

- Extortion

- Fraud

- Conflict of interest in procurement

- Gratuities/gifts

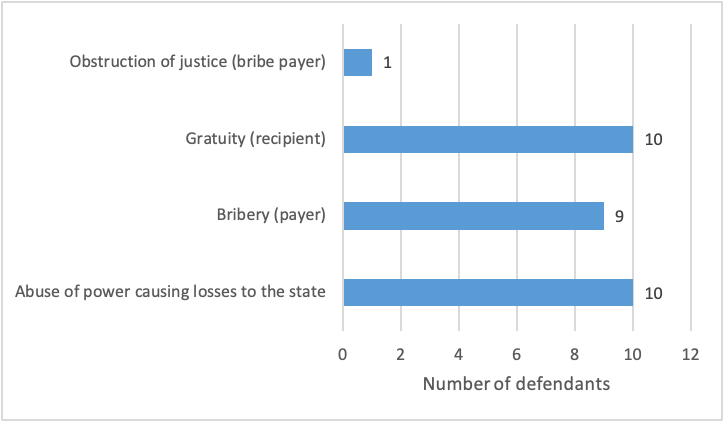

An eighth category, not specifically about corruption but part of the law, is obstruction of justice. In its indictments of the 30 forestry-related defendants, the KPK’s main (primer) charges were abuse of power, bribery, gratuities, and, in one case, obstruction of justice related to a bribery case.

Figure 2: Main (primer) charges

The 10 defendants indicted in the first two cases examined here (East Kalimantan and Riau 1) were all charged with abuse of power causing losses to the state under Article 2(1), which reads:101087432e95

‘Anyone unlawfully enriching himself and/or other persons or a corporation in such a way as to be detrimental to the finances of the state or the economy of the state shall be liable to life in prison, or a prison term of not less than 4 (four) years and not exceeding 20 (twenty) years and a fine of not less than IDR 200,000,000 (two hundred million rupiah) and not exceeding IDR 1,000,000,000 (one billion rupiah).’

For these charges the KPK had to provide evidence that (a) an unlawful act had taken place, (b) someone benefited from this act, and (c) it caused the state to suffer losses. The definitions of all three elements have provoked legal debate (see, e.g., Butt 2009 on the concept of ‘unlawfulness’).

In the 10 indictments examined here, the KPK first established which forest management and licensing regulations under Law 41 of 1999 on forestry were ‘unlawfully’ broken and how this enriched those involved. For example, in its first forestry sector case, the KPK initially charged the governor of East Kalimantan, Suwarna Abdul Fatah, with abusing and exceeding his powers as governor and breaking a whole raft of regulations and decrees of the Ministry of Forestry concerning the issuance of permits and licences in the period from August 1999 to 2002. He was then further charged with self-enrichment or the enrichment of someone else, in this case Martias alias Pung Kian Hwa and the PT Surya Dumai Group, by illegally cutting and selling almost 697,260 cubic metres of timber. The KPK used a statement by the Financial Supervisory and Development Board that calculated the loss at IDR 347 billion based on the volume of timber established by the KPK and the government’s standard pricing, not the actual sales price.

With the enactment of Law 18 of 2013 on the Prevention and Eradication of Forest Destruction, a special investigative unit under the Ministry of Forestry was set up to investigate criminal acts in relation to forest destruction, including abuse of power by government officials. Since then, KPK prosecutions have focused on bribery and illegal gratuities as the main charge, as in the cases in Central Sulawesi, Riau 2 and 3, and West Java. As part of the research for this paper, it could not be established with certainty whether the KPK’s focus on bribery charges (rather than abuse of power charges) reflected an explicit or implicit division of labour with the new unit at the Ministry of Forestry or was due to other reasons, such as the difficulty of establishing state loss to support abuse of power charges. According to one reviewer of this paper, it may become increasingly difficult to establish state loss in cases where it is no longer high-quality forest that is being illegally logged, but rather areas that, while still officially forest, only have timber of lesser quality and are already designated for conversion.

Another reason for the different prosecution strategy as of 2013 might be the change of KPK leadership in late 2012. The KPK is headed by five commissioners who are appointed to four-year terms in a sequential selection process involving first government and then parliament.c9cf1c9404b2

In the cases it prosecuted, the KPK charged the nine defendants from the private sector with bribery of state officials under Article 5(1) of Law 31 of 1999 as amended by Law 20 of 2001, which provides:

‘Any person(s) who:

a. gives or promises something to a civil servant or state apparatus with the aim of persuading him/her to perform an action or not to perform an action because of his/her position in violation of his/her obligation; or

b. gives something to a civil servant or state apparatus because of or in relation to something in violation of his/her obligation whether or not it is done because of his/her position, shall be sentenced to a minimum of 1 (one) year’s imprisonment and a maximum of 5 (five) years’ imprisonment and/or be fined a minimum of IDR 50,000,000 (fifty million rupiah) and a maximum of IDR 250,000,000 (two hundred and fifty million rupiah).’

Kwee Cahyadi Kumala alias Swie Teng was also charged with bribery under Article 5, but his main charge was obstruction of justice after the investigation against F. X. Yohan Yap had started. Among other things, he instructed other people to hide documents before they could be seized, to retroactively issue a contract to hide a bribe payment, and to provide false witness statements.

After 2013 the public sector recipients, with one exception, were charged under Article 12, as their main or primer charges, with acceptance of illegal gratuities (gratifkasi) or gifts.4066a3c16164 Article 12 puts the onus on the defendant to show that gratuities above IDR 10 million are not a bribe. It provides for four to 20 years’ imprisonment and a fine between IDR 200 million and 1 billion – the same punishment as for abuse of power under Article 2(1). It thus sets out a harsher guideline than Article 5(2), which prescribes the same sentence for the bribe taker as for the bribe payer. Article 12b provides:

‘(1) Any gratuity for a civil servant or state apparatus shall be considered as a bribe when it has something to do with his/her position and is against his/her obligation or task, with the provision that

a. when the gratuity amounts to IDR 10,000,000 (ten million rupiah) or more, it is the recipient of the gratuity who shall prove that the gratuity is not a bribe;

b. when the gratuity amounts to less than IDR 10,000,000 (ten million rupiah), it is the public prosecutor who shall prove that the gratuity is a bribe.

(2) A civil servant or state apparatus who is found guilty of the criminal offense as referred to in paragraph (1) shall be sentenced to life imprisonment or a minimum of 4 (four) years’ imprisonment and a maximum of 20 (twenty) years’ imprisonment and be fined a minimum of IDR 200.000.000 (two hundred million rupiah) and a maximum of IDR 1,000,000,000 (one billion rupiah).’

The pure bribery article is Article 11, in which the onus of proof is always on the prosecutor regardless of the bribe amount. It comes with lower sentences and has only been a subsidiary charge in the cases studied here:

‘A civil servant or state apparatus who receives a payment or a promise believed to have been given because of the power or authority related to his/her position or prize or promise which according to the contributor still has something to do with his/her position, shall be sentenced to a minimum of 1 (one) year’s imprisonment and a maximum of 5 (five) years’ imprisonment and be fined a minimum of IDR 50,000,000 (fifty million rupiah) and maximum of IDR 250,000,000 (two hundred and fifty million rupiah).’

KPK prosecutors thus maximised the potential punishment by bringing the stronger illegal gratuity charge under Article 12 as the primary charge, putting the onus of proof on the defendants, and bringing bribery charges under Articles 5(2) and 11 as only secondary charges. This has been a smart and successful strategy by prosecutors, resulting in guilty verdicts for all defendants (discussed further below).

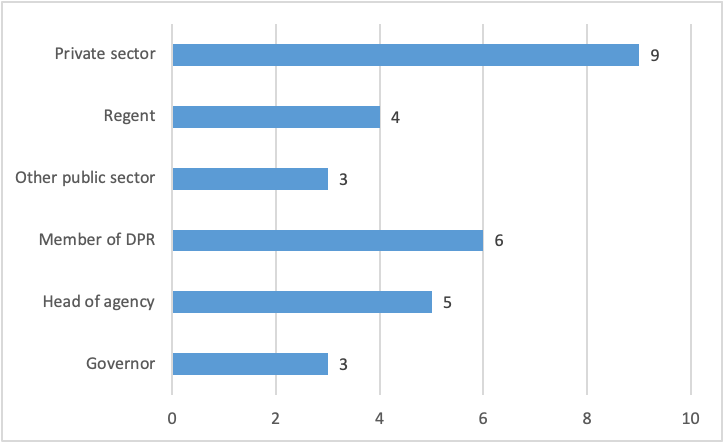

Defendant profiles and the absence of companies

The nature of the forestry sector cases, which involve the abuse of power to illegally issue licences or bribery to obtain licences and concessions, implies that private sector actors benefited from the use of those licences. In Figure 3 we have loosely grouped the defendants by sector and professional category. Among the 30 defendants there was only one woman, Siti Hartati Murdaya, the managing director of PT Hardaya Inti Plantations and PT Cipta Cakra Murdaya. The gender of prosecutors, judges, and witnesses is not always possible to establish based on their names in the verdicts, as some Indonesian names are gender neutral, but in any of these groups women seem to be in the clear minority.

The nine defendants from the private sector who were charged with bribery are all senior managers and chairs of the boards of directors of the involved companies. It is notable that of the 13 defendants in the three Riau cases, only one was from the private sector, Chandra Antonio Tan, managing director of PT Chandratex Indo Artha. The cases in Siak and Pelalawan did not result in prosecution of the involved conglomerates that bought the companies set up by the local government. In her social network analysis, Baker2e9f078daa08 observes that a key witness/potential suspect in the Pelalawan case, Rosman, who was general manager of PT Riau Andalan Pulp and Paper, absconded during the investigation. Baker also found that the investigation and prosecution stopped short of going beyond the first tier of transactions; money flows were not followed further.

The companies themselves were not charged, even though Law 31 of 1999 as amended by Law 20 of 2001 stipulates that corporations can be held liable for corrupt acts. Article 20 states: ‘(1) In the event that corruption is committed by or on behalf of a corporation, prosecution and sentencing may be conducted against the corporation and/or its managers. (2) Criminal acts of corruption committed by a corporation are action by persons either in the context of a working relationship or other relationships, undertaken within the environment of the aforementioned corporation, either singularly or jointly.’

There are two main reasons for the omission of charges against the companies involved in the cases discussed here, according to sources within the KPK and environmental watchdogs. One reason given by KPK sources is that there was no criminal procedural law for indicting corporations before the enactment of Supreme Court Regulation 13 of 2016 (after the final verdict in the cases discussed here). Another impediment, one which the KPK together with its government allies in the National Corruption Prevention Strategy are still trying to overcome, is the absence of a verified registry of beneficial ownership in Indonesia. An inter-ministerial memorandum of understanding from July 2019 foresees the establishment of an integrated database among six ministries: Justice and Human Rights, Finance, Agriculture, Energy and Mineral Resources, Medium and Small Enterprises, and Agrarian Affairs and Spatial Planning/National Land Agency.

A third possible reason, which could not be verified as part of the research conducted for this study, is that the companies were extorted by local government officials.

The KPK has indicted about 10 companies across sectors since the Supreme Court regulation of 2016. In 2019 the agency brought its first-ever corruption charges against a company in the forestry sector: PT Palma Satu, a subsidiary of the Darmex Group, whose billionaire owner, Surya Darmadi, was also indicted in the scandal.60966396caa5

Figure 3: Defendants’ professions

Length of investigation, trial, and appeals

Under law, the KPK’s combination of both investigative and prosecutorial powers comes with a special safeguard that must be seen as a response to public exasperation with the performance of the National Police and the Attorney General’s Office. Once it has moved from preliminary investigation to the investigation stage, the KPK is required to proceed to prosecution and trial.d7f46444afcd Unlike the police and the Attorney General’s Office, the KPK cannot halt the investigative process or indictments if, for example, it finds that the preliminary evidence will not hold up in court.9690ec15be3b The motivation for this requirement stemmed from the bad reputation of the Order to Terminate Investigation/Prosecution. This order provides the police and public prosecutors with the discretion to halt investigations and prosecutions and offers considerable opportunity for abuse, such as the extortion of suspects and witnesses by offering to halt investigations in exchange for a bribe.392a4b93e4e0

The Indonesian Criminal Procedure Code, in Articles 23–29, establishes a maximum detention period for accused persons of up to 40 days during the investigation and up to 30 days during the indictment stage. If the maximum penalty for the crime is greater than nine years’ imprisonment, detention can be extended up to 150 days at most by order of a district court judge. Therefore, if the accused is placed in detention the KPK investigators and prosecutors are under some time pressure to move ahead expeditiously if they do not want to release defendants before trial (and risk having them jump bail). All 30 defendants had been put in pre-trial detention.

Law 30 of 2002, which established the KPK, set strict timelines for the delivery of verdicts: 90 days from the start of trial for first instance courts, 60 days for appeal courts, and 90 days for cassation appeals.b1065b45de5f These timelines were intended to reduce the tendency for backlogs of undecided cases to accumulate, for which the Supreme Court was notorious. The timelines for the first instance and cassation trials were extended to 120 days each by Law 46 of 2009 (the so-called Tipikor law, pertaining to the jurisdiction of the anti-corruption courts). These deadlines have been adhered to in a large majority of the KPK’s cases, including the cases discussed here. In the absence of any disciplinary or legal sanctions for delayed trials, pressure came from media and public scrutiny and, perhaps, from a sense of peer pressure, as no panel wanted to be the first to oversee a trial going into overtime.

For the cases we studied, even though timelines from start of the investigations to final and binding verdicts cannot be established based on the court decisions alone, it seems that once indicted, the cases moved quite swiftly through the courts. This is remarkable, not only in comparison with the Indonesian general court system and the Supreme Court, with its huge backlog,ab3196bb7c37 but also in comparison with other countries, where large corruption cases often linger in courts for a decade or even longer.657b07a8c2b7

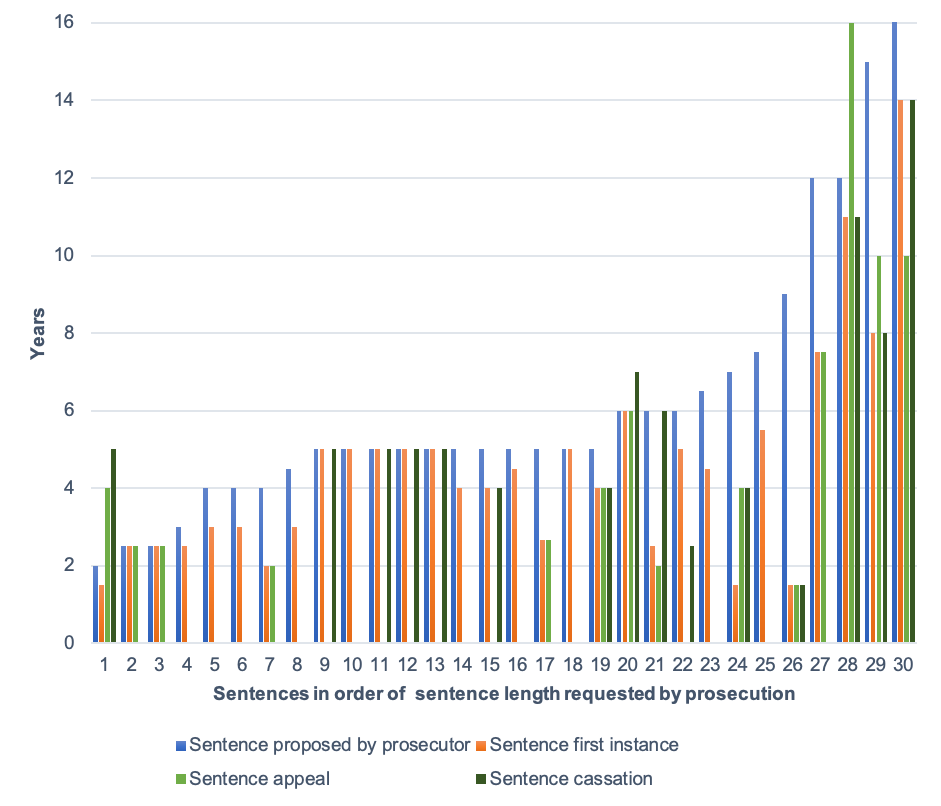

Imprisonment sentences and appeals

The average and median final and binding prison sentence (in kracht) in the 30 cases was five years. Figure 4 shows cases based on the length of sentence requested by the prosecution. The average difference between what the KPK demanded in its indictment and the final verdict is 1.37 years. Two remarkable outliers are the cases against Martias alias Pung Kian Hwa and Al Amien Nasution. At cassation level, the primary charge against Martias (no. 26 in Figure 4) was dropped and his sentence was reduced by 7.5 years. The final sentence for Al Amien Nasution (no. 29) was seven years less than requested by the KPK, also because the primary charge against him was dismissed. If these two outliers are excluded, the average difference between prosecution request and final verdict is a bit less than one year (0.96).

In the case against F. X. Yohan Yap (no. 1), the court went for a higher sentence (five years in prison) than initially requested by the prosecution (two years). Yohan Yap’s sentence is also higher than that of his superior Kwee Cahyadi Kumala (no. 22), whose final sentence was reduced to 2.5 years after his judicial review was admitted by the Supreme Court. It appears that at appeal level, the court found that Yohan Yap and his conspirators ‘only considered, thought and put their business interests first without paying attention and taking into account the interests of our children and grandchildren in the future.’ The court also observed that his actions could have destroyed the environment and ecosystem, risking floods that could have affected the livelihoods of people in the area.5d0b4a5e08ff

Figure 4: Sentencing at all levels

Figure 4 shows that half of the 30 defendants’ cases went all the way to the Supreme Court, including four case reviews (all dark green bars). Only five cases stopped at appeal level. Ten cases were not appealed. No systematic analysis as to which party appealed was conducted as part of this study. KPK prosecutors will typically ask the permission of the KPK commissioners to appeal to the higher court if the sentence is less than two-thirds of what they requested. But from media reporting it is well known that many of the defendants in KPK cases also appeal.

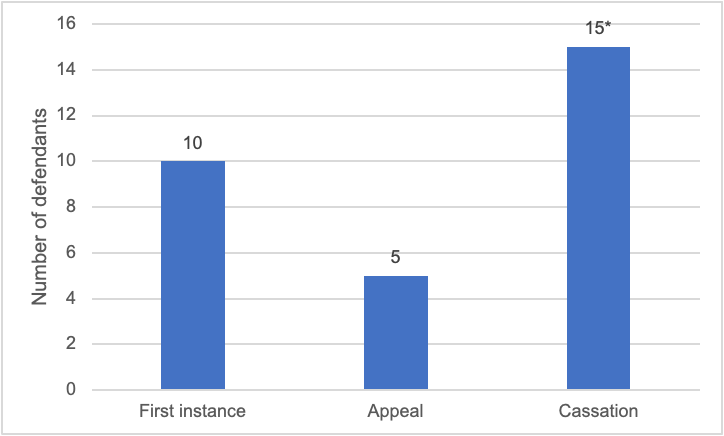

Figure 5: Court level of final verdict

* Four case reviews that went straight from first instance to case review by the Supreme Court are included here under cassations.

Appeals happened mostly for sentences above six years; however, at appeals level a higher sentence was likely. Cassation was a bit of a gamble, but only in the case of Kwee Cahyadi Kumala, which was actually a judicial review and not a cassation trial, did the Supreme Court impose a lower sentence than the one handed down in the first instance verdict. Accordingly, it would have been better for defendants if there had not been an appeal (regardless of who appealed, defence or prosecution).

Losses, asset seizure and recovery, and restitution

It is within the KPK’s mandate to investigate and prosecute cases that involve law enforcement personnel or public officials, that give rise to particular public concern, and/or that involve losses to the state of at least IDR 1 billion. Losses to the state (kerugian negara) have to be proven as part of the charge of abuse of power causing losses to the state as in Article 2(1) or Article 3, but this does not apply to the other offences listed in Law 31 of 1999 as amended by Law 20 of 2001.

What constitutes state finances (keuangan negara) and related losses to the state (kerugian negara) or losses to state finances (kerugian keuangan negara) is defined differently by different laws, with some overlaps and gaps,7717d2bb0183 and is a matter of ongoing debate. In the East Kalimantan and Riau 1 cases discussed here, where losses to the state had to be proven as part of abuse of power charges, KPK prosecutors stuck to the standard pricing of the timber that had been illegally logged, with calculations provided by BPKP.2fe6c8931f4f

However, in the media and other reporting, one can also find state loss estimates that include not only the amount of timber illegally logged and sold, but also the bribes that have been paid and any additional proven profits that have been gained from the illegal act.6c98018c7bcc In the recent case against the former governor of Southeast Sulawesi, Nur Alam, the KPK for the first time calculated the financial losses based on the environmental degradation of the land, although prosecutors shied away from formally claiming these as state losses in the indictment (see Box 1).

Irrespective of whether state loss is established or not, prosecutors can seek fines and additional penalties on top of the prison sentences. Law 31 of 1999 as amended by Law 20 of 2001 stipulates these additional penalties in Article 18(1):

‘a. The confiscation of tangible or intangible movable assets or fixed assets used to commit or being the proceeds of criminal acts of corruption, including the guilty party’s corporation where the criminal acts were perpetrated, and the same shall apply to the price of the assets used to replace the aforementioned assets;

b. The payment of compensation [restitution], the amount of which shall not exceed the amount of assets obtained through such criminal acts of corruption;

c. The winding up of the entire company or parts thereof shall take no longer than 1 (one) year;

d. The revocation of all or certain rights or parts thereof or the abolishment of all or certain benefits or parts thereof obtained or to be granted by the government to the guilty party.’

KPK prosecutors requested restitution (payment of compensation) from only five defendants, and the court agreed in all five cases (Table 1). These individuals were, notably, defendants in the first two cases in which the main charge was abuse of power causing losses to the state, so state loss needed to be established as part of the charges. In the bribery and gratuity cases that followed, only the verdict of Amran Abdulah Batalipu ordered him to pay restitution to the state. The amount, IDR 3 billion, was the amount of the bribe he received, though presumably the IDR 2 billion that was paid to him (in addition to IDR 1 billion that had previously been transferred to him) during the sting operation by the KPK should have been registered under seized assets.

To date, none of the illegally obtained licences in any of the cases discussed in this paper have been revoked because of the criminal cases considered here. In 2012, the Anti Forest-Mafia Coalition, an alliance of Indonesian civil society watchdogs, demanded in a joint press release that the KPK also go after the conglomerates that benefited from illegal licensing in the Riau cases.

Table 1: State economic losses, assets seized, fines, and restitution per defendant (final verdict), grouped by case

| Province | Defendant | State economic loss (kerugian negara) | Assets seized by court (dirampas untuk negara) | Fine (denda) | Restitution (uang pengganti) |

| East Kalimantan | Suwarna Abdul Fatah | IDR 346,823,970,564 | – | IDR 250 million | – |

| Martias alias Pung Kian Hwa | IDR 346,823,970,564 | – | IDR 300 million | IDR 346,823,970,564 | |

| Uuh Aliyudin | IDR 346,823,970,564 | – | IDR 200 million | – | |

| Robian | IDR 346,823,970,564 | – | IDR 200 million | – | |

| Riau 1 | Rusli Zainal | IDR 265.91 billion | USD 1,600 | IDR 1 billion | – |

| Tengku Azmun Jaafar | IDR 1,208,625,819,554 | IDR 6,072,626,434 | IDR 500 million | IDR 12,367,780,000 | |

| Burhanuddin Husin | IDR 519,580,718,790 | IDR 1.1 billion | IDR 500 million | – | |

| Syuhada Tasman | IDR 153,024,496,294 | IDR 5 million | IDR 250 million | – | |

| Asral Rachman | IDR 655,324,675,125 | IDR 3.13 billion | IDR 250 million | IDR 1,544,200,000, minus already seized assets of IDR 600,000,000 | |

| Arwin AS |

IDR 301,653,789,091 | IDR 500 million | IDR 200 million | IDR 850 million and USD 2,000 | |

| Riau 2 | Al Amien Nasution | – | IDR 114,337,500; 2 mobile phones | IDR 250 million | – |

| Sarjan Tahir | – | IDR 100 million | IDR 250 million | – | |

| Yusuf Erwin Faishal | – | 2 smartphones; SGD 85,000; IDR 75,000,000; USD 5,000 | IDR 250 million | – | |

| Azirwan | – | – | IDR 150 million | – | |

| Chandra Antonio Tan | – | IDR 3.32 billion; 1 mobile phone, 1 SIM card, 1 memory card | IDR 250 million | – | |

|

Azwar Chesputra |

– | IDR 975,000,000 (joint verdict) | IDR 200 million | – | |

| Hilman Indra |

– | IDR 200 million | – | ||

| H. M. Faachri Andi Leluasa |

– | IDR 200 million | – | ||

| Central Sulawesi | Amran Abdulah Batalipu | – | – | IDR 500 million | IDR 3 billion |

| Gondo Sudjono | – | – | IDR 50 million | – | |

| Siti Hartati Murdaya | – | IDR 92 million | IDR 200 million | – | |

| Totok Lestiyo | – | – | IDR 50 million | – | |

| Yani Ansori | – | – | IDR 50 million | – | |

| West Java | Kwee Cahyadi Kumala alias Swie Teng | – | – | IDR 200 million | – |

| M. Zairin | – | – | IDR 300 million | – | |

| Rachmat Yasin | – | – | IDR 300 million | – | |

| F. X. Yohan Yap alias Yohan |

– | – | IDR 250 million |

– | |

| Riau 3 | Annas Maamun |

– | SGD 224,000; IDR 713,650,000; USD 32,000; 5 mobile phones | IDR 200 million |

– |

| Gulat Medali Emas Manurung |

– | – | IDR 100 million |

– | |

| Edison Marudut Marsada Uli Siahaan |

– | – | IDR 100 million |

– |

Box 1: The Nur Alam case: An attempt to put a value on environmental degradation

The case of the former governor of Southeast Sulawesi, Nur Alam, is special because the KPK’s prosecutors for the first time not only requested a prison term, a fine (denda), and restitution (uang pengganti) for loss of revenue, but also calculated the economic loss suffered by the state from the environmental damage resulting from the illegal issuance of a mining licence. Based on testimony of an expert witness, Basuki Wasis, the actual state loss derived from three sources: environmental damage, environmental economic loss, and cost of environmental rehabilitation. That calculation was based on the Ministry of Environment Regulation 7 of 2014 on Environmental Losses Due to Pollution and Environmental Damage. After careful examination including a site visit, the expert and KPK team concluded that the total environmental state loss amounted to IDR 2.73 trillion. The KPK team also added another IDR 1.6 trillion to account for the profit obtained by the mining company, PT Anugrah Harisma Barakah (PT AHB). This brought the total value of state economic loss to IDR 4.3 trillion.

The KPK charged Nur Alam for abuse of power causing state loss in conjunction with receiving illegal gratuities (Articles 2 and 12b of Law 31 of 1999 as amended by Law 20 of 2001). It asked the court to sentence Nur Alam to 18 years in prison, a fine of IDR 1 billion, and IDR 2.7 billion in restitution. KPK prosecutors did not specifically request that Nur Alam himself pay IDR 4.3 trillion to compensate for state loss. According to the prosecutors’ explanation, the state economic loss due to environmental damages will be charged to the company, PT AHB.

The Anti-Corruption Court of the District Court of Central Jakarta sentenced Nur Alam to 12 years in prison, a fine of IDR 1 billion, and IDR 2.7 billion in restitution. Nur Alam appealed to the High Court, but the sentence was increased to 15 years, with the same amount of fine and restitution. Not satisfied with the High Court decision, Nur Alam appealed to the Supreme Court. The justices concluded that Nur Alam had only violated Article 12b on gratuities, and as a consequence the Supreme Court reduced his prison sentence to 12 years, with the same amount of fine and restitution. Notably, the District Court of Central Jakarta, the High Court of Jakarta, and the Supreme Court all clearly stated that Nur Alam was also guilty of receiving a bribe, not only a gratuity as charged by the KPK. (Anti-Corruption Court at Central Jakarta District Court, Decision No. 123/Pid.Sus-TPK/2017/PN Jkt.Pst., and Supreme Court, Decision No. 2633 K/PID.SUS/2018.)

A close examination of the Supreme Court decision shows the following inconsistencies:

- The Supreme Court concluded that Nur Alam was freed of charges under Articles 2 and 3 on state economic loss, but the Court still maintained the amount of fine and restitution for the violation of Articles 2 and 3.

- The total amount of the restitution (IDR 2.7 billion) is much lower than the bribe/gratuity received by Nur Alam. According to the court document, Nur Alam received USD 4,499,900 (equivalent to IDR 40.2 billion) from Richcorp International Ltd., the sister company of PT AHB. The KPK prosecutors also contributed to this mistake, as they only sought to have Nur Alam pay IDR 2.7 billion restitution for his crime.

Nur Alam claimed to have new evidence in his favour after the trial. The Supreme Court rejected the case review in May 2020. At the time of writing, the KPK investigators and prosecutors are still contemplating whether to formally charge PT AHB and its executives for bribing Nur Alam and for causing environmental damage and economic loss to the country.

Recommendation: A new prosecution paradigm

Tebang pilih is a term originally used in relation to forest logging. It translates as ‘selective felling’ or ‘high grading,’ terms that refer to the disputed practice of selectively cutting certain trees and leaving the rest. The expression has also been used to describe the KPK’s selectivity in pursuing cases. The agency’s obligation under Law 30 of 2002, to bring to court all cases that it investigates, has made the KPK particularly careful to start official investigations only when there is strong initial evidence, so as not to lose a case at court and spoil its near 100% conviction rate. This has led to accusations that the KPK is ‘cherry-picking’ cases, or even that it is biased in its investigations.d724a552a279 The analysis of the verdicts alone does not allow for an examination of investigative bias. The verdicts compared here do, however, suggest a selective and narrow use of tools available in the criminal justice toolbox – or to continue the forest metaphor, using simple garden clippers to cut branches of a disease-infected tree.

The KPK has indicted more than 30 defendants involved in corrupt acts related to the forestry sector, all of which resulted in deforestation and illegal commercial use of large areas of land in Central Sulawesi, East Kalimantan, Riau, and West Java. All defendants received prison sentences, but at the time of writing, most have already completed their sentences and been released from prison. The companies benefiting from the corrupt deals were not fined and never lost their illegally obtained licences.

Based on what it has requested in its indictments, the KPK can be considered relatively successful. Its charges have largely been confirmed by the courts, even if final prison sentences are on average a year lower. It is in the omission of charges against the benefiting companies, as well as the failure to request restitution of assets – full recovery of the proceeds of crime, plus damages for environmental degradation – that its indictments can be considered to fall short of the ideal. This has kept the agency from acting as the ‘trigger of change’ that the KPK has proclaimed itself to be.

These criticisms are not news to the KPK. Indeed, the agency has begun efforts to pursue the companies benefiting from corrupt deals and to assign a value to the economic loss the state is suffering due to environmental degradation. But progress has been too slow, and this has hampered the KPK’s ability to show its value in cost-benefit terms. Only two forestry-related cases have been indicted by the KPK since 2016; this stands in odd contradiction to the agency’s preventive efforts through the National Corruption Prevention Strategy and its support for the One Map and sector studies.

Based on our review, we can offer several recommendations for the prosecution of forestry-related (and similar) corruption cases:

- Implement a coherent strategy of prevention and enforcement in the sector, supported by a robust information- and knowledge-sharing infrastructure.

- Indict the companies benefiting from the corrupt deals.

- Put more emphasis on asset recovery and restitution.

- Continue putting a value on environmental degradation as a state economic loss and request restitution.

- Demand the revocation of licences if the court determines they have been obtained illegally.

In the future the KPK should not only pride itself on a near-perfect conviction record, but should innovatively and bravely clear the legal path for prosecutions in the natural resources sector and set a precedent that the National Police and Attorney General’s Office can follow. The instruction by recently appointed KPK chairman Firli Bahuri to the KPK’s enforcement department to crack down on corruption in mining and other natural resource businesses raises expectations that we will be able to analyse more forestry cases brought to court.ff8047331511

List of defendants and verdicts in order of length of sentence requested by the KPK

Following the exact numbering of decisions in the verdicts.

1. F. X. Yohan Yap alias Yohan

- Anti-Corruption Court at the District Court of Bandung, Decision No. 63/Pid.Sus/TPK/2014/Pn.Bdg.

- Anti-Corruption Court at the High Court of Bandung, Decision No. 13/TIPIKOR/2014/PT BDG.

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Supreme Court, Decision No. 624/PID.SUS/2015.

2. Gondo Sudjono

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Central Jakarta District Court, Decision No. 52/PID.B/TPK/2012/PN.JKT.PST.

- Anti-Corruption Court at the High Court of Jakarta, Decision No. 65/PID/TPK/2012/PT/DKI.

3. Yani Ansori

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Central Jakarta District Court, Decision No. 53/PID.B/TPK/2012/PN.JKT.PST.

- Anti-Corruption Court at the High Court of Jakarta, Decision No. 66/PID/TPK/2012/PT.DKI.

4. Azirwan

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Central Jakarta District Court, Decision No. 13/PID.B/TPK/2008/PN.JKT.PST.

5. Chandra Antonio Tan

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Central Jakarta District Court, Decision No. 35/PID.B/TPK/2008/PN.JKT.PST.

6. Gulat Medali Emas Manurung

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Central Jakarta District Court, Decision No. 116/PID.Sus/TPK/2014/PN.JKT.PST.

7. Totok Lestiyo

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Central Jakarta District Court, Decision No. 60/PID.Sus/TPK/2013/PN.JKT.PST.

- Anti-Corruption Court at the High Court of Jakarta, Decision No. 07/PID/TPK/2014/PT.DKI.

8. Edison Marudut Marsada Uli Siahaan

- Anti-Corruption Court at the District Court of Bandung, Decision No. 78/Pid.Sus-TPK/2016/PN.Bdg.

9. Arwin AS

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Pekanbaru District Court, Decision No. 10/PID.SUS/2011/PN.PBR.

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Supreme Court, Decision No. 226 PK/Pid.Sus/2012 (case review; rejected).

10. Asral Rachman

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Central Jakarta District Court, Decision No. 16/PID.B/TPK/2010/PN.JKT-PST.

11. Azwar Chesputra

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Central Jakarta District Court, Decision No. 12/PID.B/TPK/2010/PN.JKT.PST.

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Supreme Court, Decision No. 23 PK/PID.SUS/2012 (case review).

12. Hilman Indra

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Central Jakarta District Court, Decision No. 12/PID.B/TPK/2010/PN.JKT.PST.

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Supreme Court, Decision No. 23 PK/PID.SUS/2012 (case review).

13. H. M. Fachri Andi Leluasa

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Central Jakarta District Court, Decision No. 12/PID.B/TPK/2010/PN.JKT.PST.

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Supreme Court, Decision No. 23 PK/PID.SUS/2012 (case review).

14. M. Zairin

- Anti-Corruption Court at the District Court of Bandung, Decision No. 88/Pid.Sus/TPK/2014/PN.Bdg.

15. Robian

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Central Jakarta District Court, Decision No. 03/PID.B/TPK/2007/PN.JKT.PST.

- Anti-Corruption Court at the High Court of Jakarta, Decision No. 08/PID/TPK/2007/PT.DKI (verdict not obtained).

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Supreme Court, Decision No. 248 K/Pid.Sus/2008.

16. Sarjan Tahir

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Central Jakarta District Court, Decision No. 22/PID.B/TPK/2008/PN.JKT.PST.

17. Siti Hartati Murdaya

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Central Jakarta District Court, Decision No. 76/PID.B/TPK/2012/PN.JKT.PST.

- Anti-Corruption Court at the High Court of Jakarta, Decision No. 13/PID/TPK/2013/PT.DKI.

18. Syuhada Tasman

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Pekanbaru District Court, Decision No. 17/Pid.Sus/2011/PN.PBR.

19. Uuh Aliyudin

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Central Jakarta District Court, Decision No. 02/Pid.B/TPK/2007/PN.JKT.PST (verdict not obtained).

- Anti-Corruption Court at the High Court of Jakarta, Decision No. 312/Pen/10/Pid/TpK/2007/PT.DKI.

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Supreme Court, Decision No. 94 K/Pid.Sus/2008.

20. Annas Maamun

- Anti-Corruption Court at the District Court of Bandung, Decision No. 35/Pid.Sus-TPK/2015./PN.Bdg.

- Anti-Corruption Court at the High Court of Bandung, Decision No. 22/TIPIKOR/2015/PT.BDG.

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Supreme Court, Decision No. 2819 /K/Pid.Sus/2015.

21. Burhanuddin Husin

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Pekanbaru District Court, Decision No. 21/Pid.Sus/2012/PN-PBR.

- Anti-Corruption Court at the High Court of Pekanbaru, Decision No. 26/PID.SUS/2012/PTR.

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Supreme Court, Decision No. 804 K/Pid.Sus/2013.

22. Kwee Cahyadi Kumala alias Swie Teng

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Central Jakarta District Court, Decision No. 08/Pid.Sus/TPK/2015/PN.JKT.PST.

- No appeal, but judicial review by the Supreme Court.

- Supreme Court, Decision No. 995/TU/2016/1 PK/PID.SUS/2016.

23. Yusuf Erwin Faishal

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Central Jakarta District Court, Decision No. 29/PID.B/TPK/2008/PN.JKT.PST.

24. Suwarna Abdul Fatah

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Central Jakarta District Court, Decision No. 29/PID.B/TPK/2008/PN.JKT.PST.

- Anti-Corruption Court at the High Court of Jakarta, Decision No. 03/PID/TPK/2007/PT.DKI.

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Supreme Court, Decision No. 380 K/Pid.Sus/2007.

25. Rachmat Yasin

Anti-Corruption Court at the Bandung District Court, Decision No. 87/PID.SUS/TPK/2014/PN.Bdg.

26. Martias alias Pung Kian Hwa

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Central Jakarta District Court, Decision No. 21/PID.B/TPK/2006/PN.JKT.PST.

- Anti-Corruption Court at the High Court of Jakarta, Decision No. 05/PID/TPK/2007/PT.DKI.

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Supreme Court, Decision No. 05/PID/TPK/200/PT.DKI.

27. Amran Abdulah Batalipu

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Central Jakarta District Court, Decision No. 64/PID.B/TPK/2012/PN.JKT.PST.

- Anti-Corruption Court at the High Court of Jakarta, Decision No. 12/Pid/TPK/2013/PT.DKI.

28. Tengku Azmun Jaafar

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Central Jakarta District Court, Decision No. 06/PID.B/TPK/2008/PN.JKT.PST.

- Anti-Corruption Court at the High Court of Jakarta, Decision No. 12/PID/TPK/2008/PT.DKI.

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Supreme Court, Decision No. 736 K/Pid.Sus/2009.

29. Al Amien Nasution

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Central Jakarta District Court, Decision No. 19/PID.B/TPK/2008/PN.JKT.PST.

- Anti-Corruption Court at the High Court of Jakarta, Decision No. 05/PID/TPK/2009/PT.DKI.

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Supreme Court, Decision No. 1183 K/PID.SUS/2009.

30. Rusli Zainal

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Pekanbaru District Court, Decision No. 50/Pid/Sus/Tipikor/2013/PN.PBR.

- Anti-Corruption Court at the High Court of Pekanbaru, Decision No. 11/TIPIKOR/2014.PTR.

- Anti-Corruption Court at the Supreme Court, Decision No. 1648 K/Pid.Sus/2014.

- FWI/GFW 2002.

- 2019: 4, 6.

- At the time of writing, 1 US dollar was equivalent to approximately 15,000 Indonesian rupiah (IDR).

- Adjie 2020.

- McCarthy and Robinson 2016.

- Ardiansyah, Marthen, and Amalia 2015.

- Obidzinski and Kusters 2015.

- Baker 2020.

- KPK 2010.

- KPK 2013.

- 2015.

- 2016.

- Ministry of Environment and Forestry 2019: 6, 22.

- Messick et al. 2015.

- See also Butt 2019.

- De Sanctis 2020.

- For a small selection see the work on quality and assessment of justice systems led by Francesco Contini at the Research Institute on Judicial Systems of the National Research Council of Italy; work by the International Consortium for Court Excellence; the Judicial Effectiveness Index of Bosnia and Herzegovina, developed with USAID support; and the work of the European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice.

- See, for example, Keilitz 2018; Bencze and Ng 2018.

- Courts at regency level are called ‘district courts’ in Indonesia.

- Schütte 2016; Butt and Schütte 2014; Schütte and Butt 2013.

- Butt and Lindsey 2018: 84.