Corruption in the health sector – a violation of the right to health

Corruption in the health sector is called the ‘cancer of health systems’ because it is often a matter of life and death – especially for poor people in low- and middle-income countries. An estimated 7% of the global health budget, which amounts to more than US$500 billion, is lost directly through corruption every year, depriving people from enjoying their right to health. Corruption limits access to health services and weakens health system performance, seriously affecting patients’ outcomes and the global efforts to achieve Universal Health Coverage (UHC).

Several quantitative and qualitative studies highlight the negative impact of corruption on health outcomes, such as infant and child mortality, maternal mortality, the immunisation rate of children, and decreased use of public health facilities.bcb80f8b2a3f Corruption in the health sector – whether grand or petty – can manifest in many forms and at different points in health systems. Some common examples are bribes and kickbacks in the drug procurement process, theft of user fees, charging for free-of-cost services, using public facilities for private purposes, and unrecorded absenteeism.bfa9a673c00c

The impact of corruption becomes even more devastating in times of crises, such as the current Covid-19 pandemic. The demand for a rapid response in the context of limited evidence and evolving information leads to governments making hasty decisions that lack transparency and oversight.

Several cases of corruption and decreasing transparency have been reported since the outbreak in early 2020. A report from Transparency International Health Initiative found several cases of informal payments, theft, absenteeism, favouritism, manipulation of data, overcharging, and false treatment reimbursement claims in more than 30 countries. Covid-19 has also amplified corruption pressures in procurement, resulting in inflated drug prices, shortages in medicines and equipment, and the spread of falsified and substandard products. With the recent roll-out of Covid-19 vaccines, the world is already bracing for corruption in procurement processes and witnessing queue-jumping behaviour of high-level political leaders, wealthy individuals, and family members of health professionals in Canada, Peru, Argentina, Spain, South Africa, and Poland, among others.

Equally damaging has been grand corruption during Covid-19. A blog post from U4 highlights how unscrupulous political leaders have taken advantage of relaxed emergency procedures and approached this crisis as an opportunity for graft, putting people’s right to health at risk.

Anti-corruption measures in the health sector are critical to respond effectively to current and future global health challenges and to achieve the right to health for all. A 2016 Cochrane Review specified some strategies as the main evidence-based anti-corruption interventions in the health sector, such as fraud detection, independent complaint mechanisms, guidelines regulating physician–industry interactions, internal controls to strengthen financial systems, and reduced incentives for informal payments. However, they concluded that there is limited evidence regarding how best to reduce corruption, especially in health emergencies.

Other broader strategies include building institutional integrity, and increasing transparency, monitoring, and accountability in all matters governing the health sector combined with reduced incentives for corrupt practices.e0407ff269d9 The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) has stressed building multi-stakeholder partnerships and using multiple avenues to promote accountability and improve service delivery in the health sector.

Donors can contribute to health sector anti-corruption efforts by using human rights mechanisms such as the UN Universal Periodic Review (UPR). This concept is complemented by the paper by Sekalala et al.bf1fe34c795b that argues for using the UPR to strengthen anti-corruption measures, transparency, and accountability to reduce corruption in the health-care sector.

Addressing health sector corruption using the Universal Periodic Review process

The Universal Periodic Review process

The UPR is a human rights mechanism which periodically reviews the human rights records of all UN Member States with the aim of improving the human rights situation in all countries and addressing violations wherever they occur. It is a state-driven process led by the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC), and each state is accorded the opportunity to declare what actions they have taken to fulfil human rights obligations.

The review process assesses the human rights records of each state every four and a half years. Reviews takes place in three sessions every year, each session taking two weeks and reviewing up to 16 states, thus completing 192 states in one cycle. To date, two cycles of the UPR (2008–2011 and 2012–2016) have been completed and the third one (2017–2022) is underway. The process of the review is explained in the following infographic.

Universal periodic review

Source: UNHRC. Maximizing the use of the Universal Periodic Review at country level.

Calling out health sector corruption in the UPR: A work in progress

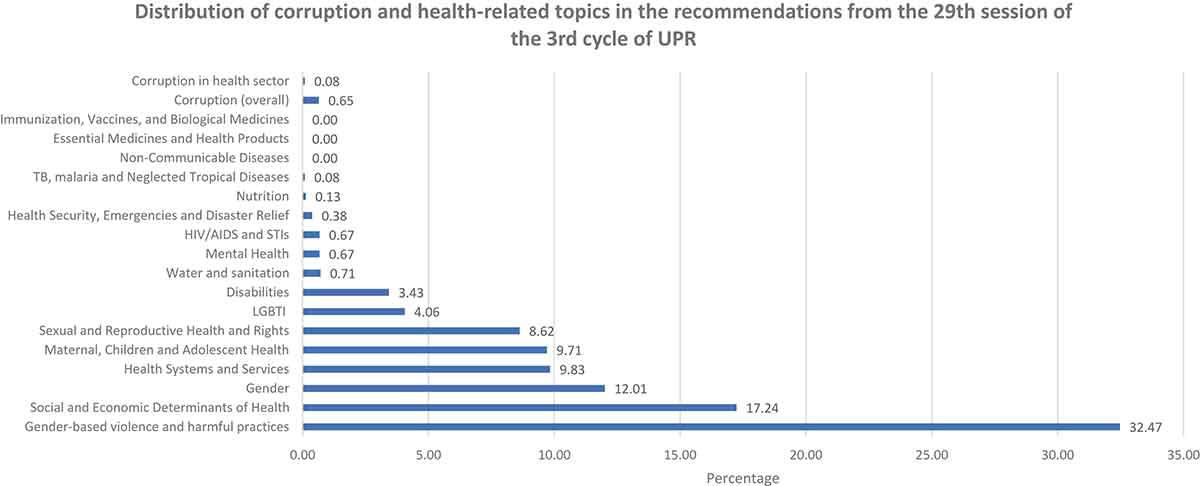

Evidence suggests that the UPR mechanism is calling attention to a variety of health-related human rights issues. We analysed all 142 documents produced during the 29th session of the UPR where human rights records of 14 states were reviewed in January 2018. We found that of 2,632 recommendations made during that session, 1,168 (44%) were health related (see Figure 1). However, the mechanism has rarely been used to identify corruption in the health sector as a human rights concern.

Only two of the 17 corruption-related recommendations (0.34%) focused on corruption in the health sector. Seven of these recommendations specifically demanded actions against corruption in the judicial system; eight recommendations related to general anti-corruption actions, i.e. asking states to implement relevant laws and intensify anti-corruption efforts; one recommendation concerned the need for legislation related to private sector corruption; two recommendations centred on combating corruption in the health sector; and one recommendation demanded the rejection of legislation that weakened anti-corruption efforts.

Eleven out of the 14 states mentioned corruption in their national reports; however, this was only in reference to their efforts, progress, or achievements to combat the issue in general. The UPR has significant potential in addressing corruption in countries’ health sectors, but it remains largely underutilised. There is an opportunity for donors to continue playing a supportive role in the process with a view to improving its efficacy and effectiveness.

Figure 1: Distribution of corruption and health-related topics in the recommendations from the 29th session of the third cycle of UPR (January 2018).

Source: Sekalala et al. 2020.

Leveraging the potential of the UPR: A catalyst for change

Although the UPR process has the potential to identify health sector corruption, we have limited knowledge about its effectiveness on the human rights performance of the states. A midterm assessment report in 2014 concluded that 48% of the UPR recommendations were either fully or partially implemented in only two and a half years after the first cycle of the UPR. Moreover, based on the experience with other mechanisms such as the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC), we believe that opportunities exist to highlight and address health sector corruption through this mechanism.

What are the entry points for donor engagement in the UPR process?

The UPR process relies on active state engagement throughout. States must prepare background documents for the review, in close cooperation with civil society (see Table 1). Civil society can play a role in raising issues of health sector corruption and states themselves can also acknowledge the issue. Other phases of the process, such as advance questions, stakeholder reports, and interactive dialogue (where states can pose questions, comment, or make recommendations), also offer entry points to highlight health sector corruption throughout the process.

Recommendations arising from the UPR process form the basis upon which the states are required to take actions. The post-review process offers further engagement points to address corruption, eg coordination with the states at national level for implementation of the recommendations, during the midterm reporting, and when reporting for the subsequent UPR sessions. A collective donor response has the potential to improve the process and promote its use in addressing corruption as a means of achieving the right to health.

How can donors contribute in highlighting health sector corruption in the UPR process?

Before and during the review

Donors can play an active role in making health sector corruption more visible on the UPR process agenda. They can provide specific guidance to state parties and civil society to highlight that corruption causes specific risks within the health sector, and that this undermines the realisation of the right to health. Such guidance is needed for both the compilation of information at national level and during the UPR sessions. Since the UPR process is an inter-governmental procedure, it is important for donor agencies to lobby other governments to raise questions regarding health sector corruption and propose recommendations to the state under review. Donors can use a variety of methods to achieve this goal.

Political dialogue

Commitments to prevent and combat health sector corruption should be anchored in high-level policy dialogue between partner governments, donors, and civil society. Framing corruption in the health sector as a human rights violation can provide a more solid basis for the dialogue. Such political dialogues can be carried out with the governments of the states under review, the National Human Rights Institutes (NHRIs), and the delegations of Member States who participate in the interactive discussion as part of the UPR, to encourage them to ask questions and propose recommendations on health sector corruption.

Training and education

Analysis by Sekalala et al.892b5eb539ff shows that corruption in the health sector is rarely discussed and even when it is and recommendations are made, they are general exhortations to ‘fight corruption.’ While this shows awareness of the problem, general recommendations do not help targeted state action. It is, therefore, important for donors to support the sensitisation and education of stakeholders (such as civil society, national human rights institutions, governmental officials, and health officials) on the link between corruption, health outcomes and the right to health, and how to leverage the UPR platform to catalyse anti-corruption approaches in the health sector. Such training should focus on illustrating corruption in the health sector as a human rights issue, raising specific questions, and establishing more specific recommendations – for instance, making the procurement process open, transparent, and free of corruption. In the subsequent review, states would then submit specific measures they have taken in response to the recommendations.

Shadow reporting

Shadow reporting is an integral part of the UPR process, and involves independent reports from stakeholders to supplement the information from the state under review. Stakeholders can raise human rights violations and provide information on the status of a country’s actions to fulfil its human rights obligations. Such reports are important as they may give a critical and different picture than the report prepared by the country under review. A summary of these reports is prepared by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and becomes an official part of the UPR process. Information contained in this summary can be referred to by any of the states taking part in the interactive discussion during the review.

Donors and development partners can support stakeholders, such as civil society, to compile shadow reports and, being stakeholders themselves, they can use the forum to submit information and comments on health sector corruption which can be added to the ‘other stakeholders report.’ They can also lobby other Member States to refer to their report for discussion during the interactive dialogue.

Technical assistance and capacity building

Funding and facilitation of technical support for civil society and the media is crucial. This is not only to assist them to participate proactively in the UPR process – highlighting corruption in the health sector as a major violation of the human rights – but also to systematically monitor implementation of the specific recommendations. A critical requirement in this regard is for civil society to be aware of the UPR process and how the right to health is being compromised by corruption.

Civil society needs to be educated on how corruption breaches the state’s duty to respect, protect, and fulfil the right to health. For instance, civil society organisations could be better prepared for the different ways corruption can manifest in the health sector, how it takes place, and which segments or processes face the most risk. Donors can assist and train civil society in writing their shadow reports for the UPR process. Civil society groups could contribute to the political debate by producing alternative reports on their country’s compliance with the UPR recommendations.

Donors can provide short-term technical assistance to support preparations for the dialogue and to create reports, which should include reviewing and/or assessing the health sector corruption and its impact on human rights so that the issue receives more recognition during the UPR process.

After the review

Including benchmarks in aid agreements

The UPR process obliges states to take concrete steps towards implementing the recommendations made during the process and improving the overall human rights situation in their countries. Development agencies can assist partner countries to define specific indicators or benchmarks of progress, and may integrate them into development assistance agreements for the health sector to ensure regular monitoring. Before issuing and/or renewing aid agreements, development assistance agencies can hold states to account for how they have followed up on previous UPR recommendations regarding health sector corruption.

Linking existing programmes with UPR recommendations

Working with governments and civil society, donors should map the links between existing aid-funded programmes and UPR recommendations as a way of assessing the relevance of current initiatives.

Monitoring the implementation of recommendations

States are encouraged to submit a midterm report on the implementation of the UPR recommendations to the UNHRC. This provides a further opportunity for donors to support and encourage the state and civil society in monitoring the progress of implementation. They could engage in discussions with the partner government as to the status of the recommendations regarding health sector corruption, where gaps exist, and where support is needed. Donors may also prompt states to include civil society in the exercise and provide assistance for this purpose.

Conclusion

As a human rights mechanism, the UPR has significantpotential in tackling corruption in countries’ health sectors and holding governments accountable for their actions – or inactions. While the issue is rarely discussed during the process and its recommendations, there are specific ways in which donors can support the mainstreaming of health sector corruption challenges into governance reform. Donors can take various measures to raise the corruption issue at this forum, and provide support and guidance to states and civil society organisations in implementing and monitoring the measures recommended during the review’s process. Such a collective donor response has the potential to improve the UPR process and champion its use to tackle corruption in the health sector – and by doing so, achieving the right to health for all.

Annex

Types of corruption in the health sector

| Area of process | Types of corruption and problems | Results |

| Construction and rehabilitation of health facilities |

|

|

| Purchase of equipment and supplies, including drugs |

|

|

| Distribution and use of drugs and supplies in service delivery |

|

|

| Regulation of quality in products, services, facilities, and professionals |

|

|

| Human resources management |

|

|

| Medical research |

|

|

| Financial management |

|

|

| Service delivery |

|

|

Source: Spector 2005. Used with permission of the publisher.

- Hanf et al. 2011; Vian 2010; Muldoon et al. 2011; Fagan 2010; Lin et al. 2014.

- See Vian and Crable 2016; Annex.

- Vian 2020; Gaitonde et al. 2016.

- 2020.

- 2020.