Query

How do tax authorities crack down on civil society? What signs might suggest that a tax policy is being used to target dissenting voices, or that a tax authority has ulterior motives in pursuing certain entities?

Background

Tax is one of the key areas that policymakers use to influence the economy through fiscal policy, which refers to the extent and composition of spending and borrowing (IMF n.d.). Fiscal policy typically aligns with the nation's current economic conditions and may involve addressing any ongoing economic crises through interventions. A government may change fiscal policies as one of the responses to a crisis through boosting activity through discretionary spending or tax cuts, or they might opt for tax systems that tax high-income households at a higher rate than lower-income households (IMF n.d.).

While national governments are responsible for setting fiscal policy, tax authorities are set up as directorates or units within the Ministry of Finance (or equivalent) or as unified semi-autonomous bodies (OECD 2024:139). The role of a tax authority is to collect the revenue that helps pay for public spending by governments, most frequently through taxes on personal income, corporate income, and the purchase of goods and services (OECD n.d.). The revenue collected is typically used as support for education, welfare, pensions, health services, transport and others. According to the OECD (n.d.), an effective tax system should be both fair and efficient.

However, despite changes to fiscal policy responding to economic conditions, there may also be political motivations driving changes too. Influences such as the date of elections and the ideology of the government have also been found to determine fiscal policy decisions (Gaspar, Gupta and Mulas-Granados 2017:6). In other cases, fiscal policy has been strategically used to target political opponents, in both democracies and more autocratic leaning countries (Kovarek and Dobos 2023). An example noted by Kovarek and Dobos (2023) is the public spending of governments in certain countries that have imposed austerity measures on municipalities with opposition mayors while at the same time offering additional resources to those municipalities that support the incumbent government.

Shifts in fiscal policy and adjustments to the tax policy can also target civil society and independent media, particularly individuals and entities that have vocally criticised a government’s actions. This use of law and legal systems to silence civil society and independent media is referred to as ‘lawfare’ by Lemaître (2022). Lawfare can include adopting restrictive laws, creating false accusations or launching investigations into the work of activists and organisations (Lemaître 2022). Another conceptual term proposed by Chaudhry (2022:554-555) is ‘administrative crackdown’, which is the use of legal restrictions to create barriers to entry, funding and advocacy by non-profit organisations. States might use administrative crackdown as a repressive strategy to impede the work of the non-profit community (Chaudhry 2022). For example, a government might manipulate tax legislation to target civil society more widely, specific entities or individuals or make false claims of tax evasion to imprison individuals. This should be considered against the backdrop of civic space at a global level being at its most restricted for several years. According to CIVICUS’s most recent State of Civil Society report, only 2.1% of the global population live in countries with open civic space (2024:8).

However, identifying when tax policy is used to deliberately target civil society is a difficult task. In many cases, countries tend to impose tax concessions for non-profit entities with public benefit requirements for eligibility (OECD 2020:42).

Therefore, given that non-profit organisations are often given such preferential tax treatment, this means they are often liable to more checks and audits by oversight bodies, such as the tax authority (OECD 2020). There are often legitimate reasons that authorities may investigate a non-profit organisation that benefits from tax concessions. The OECD (2020:72) notes that there may be a risk that fraudsters may pose as such an entity to falsify tax returns to defraud the government or it could occur through the terrorist abuse of non-profit organisations, although the report states that this is rare across OECD countries. These potential risks lead tax authorities and oversight bodies to identify and track suspicious entities and activities (OECD 2020:72). However, this use of investigation and increased scrutiny by tax authorities may also be used against non-profit organisations, making the distinction between legitimate and oppressive oversight difficult.

When governments and other public officials use state institutions and policy to close civic space and target civil society actors and independent media, this can be enabled by and constitute a form of corruption. Corruption is defined as ‘the abuse of entrusted power for private gain’ by Transparency International (n.d.). Under this definition, the abuse of state functions leads to a ‘private gain’ for the political party or the officials in the sense that they can consolidate their power through silencing opposing voices. The use of tax policies and tax authorities can represent an abuse of state resources through policymaking, whereby policymakers use fiscal policy to consolidate their own power. Finally, these actions could indicate state capture. State capture is a type of systemic corruption where narrow interest groups (such as a specific sector or high-level public officials) take control of the institutions and processes through which public policy is made, shaping them to serve their own interests (Dávid‑Barrett 2023). Those that aim to limit civic space could use tax authorities and fiscal policy (and potentially others) to curtail freedom of expression and association. Not only does this constitute a form of corruption but it can also have the effect of silencing anti-corruption organisations and activists from further holding those in power to account.

This Helpdesk Answer looks at a range of cases where there have been reports that the tax policy and tax authorities have been used to restrict civic space. However, there are nuances in the following case studies. This paper then attempts to identify red flags when the tax policy has been changed or tax authorities launch investigations that could indicate that authorities are going beyond routine audits and oversight of non-profits and that these are instead being used to target and undermine civil society actors and journalists. Finally, it investigates the literature that provides some suggestions on how to safeguard civil society actors from such repressive actions.

The use of tax policy and tax authorities to target civil society and independent media

The following section primarily relies on reports by the media and civil society on administrative crackdowns on non-profit organisations and independent media, as well as some cases of arrest of civil society actors and journalists for tax-related issues. Given that few systematic reviews of all tax-related administrative crackdowns have been undertaken, this section mainly relies on illustrative case studies which help to build a larger picture of the issue. The case studies generally indicate either: i) changes to the tax policy that make the operation of non-profits more difficult, or, in the more extreme cases; ii) actively targeting, using tax authorities and tax policy to suppress actors. It should be noted that while the reports tend to claim that the measures taken by governments constitute administrative crackdowns, this may not in fact be the case for every report and some instances may constitute legitimate investigations and/or changes to national fiscal policy without the intention of suppression.

Changes to tax policy or other relevant legislation and regulations

In many countries, tax policy is favourable to non-profit organisations, so that they can allocate more funds to their activities and encourage charitable donations by others. For example, in many European Union (EU) member states, non-profit organisations enjoy tax benefits and, in some states, are exempt from taxation on non-distributed profits (European Commission 2023:4). While member states are free to decide and define whether they want to provide tax advantages for non-profit organisations and charitable donations (European Commission 2023:8), many of them choose to provide such advantages for causes they deem to have a public benefit.

Similarly, in several countries independent media receives tax concessions. France, Germany, Ireland, Italy and the UK have tax regimes and reliefs to encourage a free and plural media, and in other countries newspapers typically pay no value added tax (VAT) (Deane 2021: 13). However, in authoritarian states this kind of indirect government subsidy has been used to weaken independent media and only strengthen pro-government media (Deane 2021: 16).

An assessment of OECD countries found that public benefit is generally measured in terms of welfare, education, scientific research and healthcare (OECD 2020:42). The tax relief tends to be separated into two approaches: to exempt all or specific income or to consider all forms of income taxable, but to allow the entity to reduce its taxable income through current or future reinvestments towards the fulfilment of their ‘worthy cause’ (OECD 2020:42). Countries also offer preferential VAT treatment to exempt them from collecting VAT on certain or all supplies (OECD 2020:43).

Another form of tax concession is that non-profit organisations are exempted from or have a reduced rate of VAT (European Commission 2023:5). These tax concessions are justified generally among EU member states if ‘they result in a larger increase in social welfare than that which government could have otherwise achieved through direct spending’ (European Commission 2023:6). Another frequently cited argument is that charitable giving and institutions engaged in it strengthen civil society and decentralise decision-making, and so are important features of a democratic society (European Commission 2023:6).

Therefore, many non-profit organisations and independent media organisations are reliant on the additional financial resources that tax concessions provide. However, changes to the tax policy which remove these tax concessions and other benefits means that these resources may be quickly taken away.

In some cases, this may be done under the guise of designating them as ‘terrorist-supporting organizations’ (Lagasse 2024). For example, in the US, concerns were raised by civil society and the media about a bill submitted in 2024 (the Stop Terror-Financing and Tax Penalties on American Hostages Act) which would give the government authority to remove non-profit’s tax-exempt status (Lagasse 2024). Those opposing the bill said it introduced powers that could be easily abused by the executive branch without providing the non-profit an opportunity to defend itself in front of an independent and neutral decision-maker (Lagasse 2024). Others (Herman 2024) said that it could be used to punish dissent and be disproportionately used against groups that support Palestinian causes. Nonetheless, the bill was not passed after failing to secure enough votes (Herman 2024).

The removal of tax concessions can be done in a targeted manner towards specific organisations that support causes or conduct activities that the government disagrees with. For example, in 2021, the Israeli supreme court ruled in favour of a measure that denied tax-exempt status to an Israeli registered group running a school in the West Bank as the school educated exclusively Palestinian and not Israeli children (Bashi 2021). This is despite the Israeli Tax Ordinance exempting non-profit organisations from income tax if they perform a ‘public purpose’ such as education. Bashi (2021) argues that decisions like these could potentially financially burden other civil society groups that provide services to Palestinians, despite Israeli registered groups retaining tax breaks when they provide services to Israelis. A draft bill was also proposed in the Knesset in 2023 that would impose a 65% tax on foreign government donations to Israeli and Palestinian non-profit organisations, which has faced widespread criticism (Freedman 2023).

In Pakistan in 2017, a new non-profit tax law was introduced that meant that organisations which spend 15% or more of their budget on administrative costs would have these costs taxed at a rate of 10%, as would any funds left over at the end of the fiscal year if they totalled more than 20% of the organisation’s budget (Saeed 2017). Critics (Saeed 2017) viewed this as an ongoing crackdown on civil society, although the government denied this was the case and stated it was aimed to cut down on the misuse of funds by NGOs. However, these is little evidence to suggest that the imposition of tax is a response that addresses the misuse of funds. The government had previously closed other non-profit organisations such as Save the Children with an order to freeze all activities, showing a deteriorating situation for civil society (The New Humanitarian 2015).

In Venezuela, the tax exemption for non-profit organisations that involved activities of public interest was changed in 2022 so that these organisations are no longer exempt from any taxes (Acceso a la Justicia 2022:18). Similarly, earlier in 2013, the Zambian government also revoked tax exemption for non-profits and other public benefit organisations, due to what the Ministry of Finance characterised as rampant abuse of the exemption (The Herald 2013).

Tax reductions for donors

In many countries, such as across most of the EU, private (both individuals and companies) and institutional donors of non-profit organisations are granted tax reductions (European Commission 2021:5). According to the OECD (2020), given the importance of philanthropy for the non-profit sector, many countries provide preferential tax treatment to those who donate, which typically includes tax incentives for philanthropic giving. In this sense, many countries’ tax systems actively support philanthropy (OECD 2020). This may include income tax relief for donors, the ability of charities to reclaim tax on donations, inheritance tax benefits and others.

Policies may be used to deter philanthropists through changing the tax policy to provide fewer tax incentives (Chaudry 2022). For example, in Mexico, the government proposed changes to the tax policy that would reduce the funding of non-profit organisations through removing specific quotas for tax-deductible donations (CIVICUS 2021). The Mexican organisations stated that the changes would take away incentives for donations, which would affect thousands of organisations that rely on charitable donations (CIVICUS 2021). The civil society group GIRE stated that this was in line with a series of measures aimed at increasingly restricting the fundraising of non-profit organisations, particularly small, local or emerging civil society organisations (CSOs) (CIVICUS 2021).

Selective enforcement of tax policy

The tax policy may also be manipulated to impose penalties or fines on certain organisations. This could include enforcing obscure regulations selectively against specific groups while ignoring similar infractions by others (Lagasse 2024). In more extreme cases, authorities may even use potentially false charges of tax avoidance or evasion to arrest civil society actors. At times, legal loopholes may have been used by authorities, making it difficult to ascertain whether these arrests and fines are legitimate or not.

For example, in Cambodia, the government reportedly accused an independent newspaper of owing a tax bill to the equivalent of €5.3 million (Akyavas 2017). This followed the closures of several radio stations and other independent media outlets. The newspaper denied the claim, stating that it had operated at a loss since 2008 and accused the government of inflating the amount owed and failing to look at their accounts or audit its books (Akyavas 2017). Critics (AP News 2017) stated that this constituted a restriction of freedom of the press and that, given that most Cambodian media are owned by the government or business operators with close connections to the authorities, this constituted a crackdown on independent media.

In a similar reported restriction of independent media, in Belarus, five members of the Belarus Press Club were detained and questioned by the Department of Financial Investigations on suspicion of tax evasion (Frontline Defenders 2021). Press Club Belarus is a platform for the professional development of Belarusian independent media and journalists and monitors the compliance of Belarusian media materials with journalistic standards (Frontline Defenders 2021). While one member was later released and deported to Russia in December 2020, the other four were indicted and remain in detention. In 2020, hundreds of Belarusians were arrested, with the Belarus Press Club being vocal against these cases. It is believed by other non-profit organisations that these journalists were targeted solely due to their work in Belarus, using tax evasion as an excuse (Frontline Defenders 2021).

In Azerbaijan, an investigative journalist was sentenced to seven and a half years in prison due to charges of abuse of authority, embezzlement, tax evasion and illegal trading (RSF 2016). However, the international non-profit organisation Reporters Without Borders (2016) stated that this was a way of silencing her due to her campaigning in a country that ranks particularly low on freedom of the press.

And, in the Philippines, a Nobel prize winner and co-founder of the online news site Rappler, Maria Ressa, was charged with tax evasion but argued that the case was politically motivated (Al Jazeera 2023). Ressa and Rappler faced five government charges of tax evasion from the sale of Philippine depository receipts, which are typically used for companies to raise money from foreign investors (Al Jazeera 2023). They were acquitted in 2023; however, they are also appealing a cyber-libel conviction that carries a sentence of around seven years in prison (Al Jazeera 2023).

In Kazakhstan, in 2017, the Special Inter-District Economic Court of Almtay found the human rights NGO International Legal Initiative (ILI) guilty of failing to pay taxes (Amnesty International 2017). The ILI stated that the tax inspection and legal case were designed to intimidate and harass them for the work they do, particularly as a punishment for legal assistance to protestors who were detained in 2016 (Amnesty International 2017). The inspection followed a written complaint from an individual who was described as a ‘concerned’ citizen and who had accused the non-profit organisation of being linked to the public protests that had taken place which, despite being peaceful, had not been authorised by authorities. The ILI was ordered by authorities to pay fines for allegedly failing to pay taxes, using an ambiguous legislative provision on tax exemptions to argue that they had to pay tax on income (Amnesty International 2017).

In 2021, at least four environmental rights defenders in Vietnam were imprisoned on charges of tax evasion, reportedly indicating a pattern in the use of the country’s tax laws to criminalise environmental leaders and shrinking civic space (FIDH 2022). Authorities had reportedly used loopholes in the legislation on corporate tax income (which designate non-profit organisations as income tax exempt, but these laws are reportedly unclear), and prison sentences for the activists ranged from two and a half years to five years (FIDH 2022). One individual was denied access to his lawyer during detention, and his family was not allowed to attend the court hearing (FIDH 2022). In 2023, another human rights defender in Vietnam was sentenced to three years imprisonment on tax evasion charges related to the work of an environmental rights campaign group, Centre of Hands-on Action and Networking for Growth and Environment (CHANGE) (Frontline Defenders 2023). Several others have also reportedly been falsely accused of tax evasion (Frontline Defenders 2023).

Foreign agent laws, restrictions on funding, and the role of tax authorities

Other legislative changes, particularly the so-called foreign agent laws, may require non-profit organisations to publicly declare the identity of all donors to tax authorities, which, in certain contexts, may expose them to risks. First introduced by the Russian government in 2012 (OSF 2024), similar foreign agent laws undermine the legitimacy and public image of non-profit organisations and independent media through the foreign agent label and can curtail the ability of organisations from operating through fines for non-compliance. This legislation typically designates a non-profit organisation that receives a certain percentage of its funding from overseas sources as a ‘foreign agent’, and the establishment of such organisations in many countries leads to fines and imprisonment (Lakmusz 2024). This severely limits the amount of foreign funding that organisations can obtain, which many non-profit organisations rely on financially. This in practice may result in limitations on the amount of funding as non-profit organisations may try to remain under the threshold that would prompt the obligation to register. These laws only apply to non-profit organisations and not other entities, such as private businesses, that receive foreign funding.

Many countries have also passed legislation prohibiting all foreign funding, in addition to foreign agent laws and less stringent limitations on foreign funding. Chaudhry (2022:551) illustrated the countries that had passed legislation restricting the use of foreign funds by non-profit organisations up until 20170bcd108cf713 (countries shaded in a darker grey had passed foreign agent legislation):

Figure 1: Countries that had passed legislation restricting the use of foreign funds by non-profit organisations by 2017

Source: Chaudhry 2022:551

Further analysis by Chaudhry on data from 1990 to 2013 found that there were over 100 administrative crackdowns (in terms of barriers to foreign funding) on non-profit organisations in autocracies and over 100 in hybrid regimes (Chaudhry 2022:568). Conversely, there were only around 30 crackdowns in democracies, indicating that this was primarily an issue in countries with lower levels of democracy. However, given that this data was only up until 2013, there have been several changes where democracies have enacted such laws. However, the opposite trend is seen in barriers to the political activities of non-profit organisations, which shows that democracies have had more crackdowns than autocracies and hybrid regimes in that period (Chaudhry 2022:568).

In 2013, Russian tax inspectors conducted searches of the offices of several international non-profit organisations, including Human Rights Watch and Transparency International (BBC 2013). The Russian foreign agents law obliged foreign-funded non-profit organisations to register as foreign agents, and failure to do so carried a heavy fine and potentially a two-year prison sentence (BBC 2013). Critics of the law and the raids argued that it was being used as a mechanism to crush dissent after mass protests (BBC 2013).

In 2023, a law was proposed in the Republika Srpska (one of the two entities of Bosnia and Herzegovina) that would require non-profit organisations that are financially or in some other way assisted by foreign entities to register as agents of foreign influence on a registry. The non-profit organisations would be obliged to submit semi-annual and annual financial reports to the Ministry of Justice, who would then submit its financial report to the tax administration for review/control of financial operations (Council of Europe 2023:5). The tax administration would then be responsible for detecting irregularities.

El Salvador’s president in 2021 proposed a law that would require media outlets and journalists receiving funding or payments from abroad to register as foreign agents. In response, the Committee to Project Journalists stated that ‘by labelling journalists and outlets as foreign agents, President Bukele is taking even more aggressive steps to limit the space for independent, critical media in El Salvador’ (CPJ 2021). An additional measure in the proposed law was that those who register must pay a 40% tax on every transaction that comes from a foreign source (CPJ 2021).

In 2021 in Kazakhstan, according to Frontline Defenders (2021), the tax authorities ordered a three-month suspension on the operation and activities of three human rights organisations and imposed fines for alleged violations in the reporting of foreign funds. However, the resolutions against the organisations were repealed due to insufficient evidence. The organisations gave different reasons for the reported discrepancies in their reported tax submissions, including fluctuations in the exchange rate, the return of unspent funds to donors, and a mistake in the duplication of a donation from a donor (which was later dealt with) (Frontline Defenders 2021). Human rights organisations noted that tax authorities in Kazakhstan have been used to target civil society that work to protect human rights (Frontline Defenders 2021).

Later in 2023, the Ministry of Finance in Kazakhstan published a list of entities and individuals who receive international funding, claiming that this was in accordance with the legal changes made to the Kazakh tax policy in 2022 (Transparency International 2023). Kazakhstan does not have a foreign agents law, however, these recent actions were considered as contributing to a similar narrative that civil society entities serve foreign actors’ agendas (Transparency International 2023). Moreover, human rights, media and election monitoring non-profit organisations are mandated by law to report foreign funding to tax authorities, with any mistake subject to penalties (Bajelidze 2024).

The European Commission in their principles on non-discriminatory taxation of charitable organisations and their donors (2023) notes that the commission has pursued compliance assessments of member states’ national laws and opened cases dealing with the refusal to grant personal or corporate income tax relief for donations to charities established in other member states (European Commission 2023:2). The court has noted that many member states do not allow the same tax relief to foreign charities as they do for domestic ones (European Commission 2023:2). Other cases have involved instances of higher income taxation of non-resident charities. The court ruled that, in these cases, discrimination against foreign charities is ‘incompatible with the free movement of capital’ (European Commission 2023:2). This means that once entities receive a certain tax treatment under national law, then it should provide the same non-discriminatory treatment for comparable foreign charities and donations made to such entities.

Burdensome tax audits

Tax audits are important activities conducted by authorities, as these reviews ensure that entities are paying tax correctly according to regulations. However, these could be used as a restrictive measure where authorities alter obligations to impose additional or excessive requirements on targeted entities, such as obliging them to submit detailed financial returns on a regular basis or risk being shut down (Markus 2015). This can present opportunities to initiate legal proceedings against and penalise an audited entity on either genuine or spurious charges of tax violations.

Heightened scrutiny through audits also preoccupies the audited entity with compliance tasks and may led to reputational damage (in cases where they have not transgressed tax regulations) and financial strain, preventing their ability to hold power to account. This is sometimes referred to as having a ‘chilling effect’ (Khardori 2024). Finally, investigations by tax authorities might gather sensitive information, such as lists of donors, funding sources and beneficiaries, which could be used as leverage to intimidate critical voices and make people less likely to provide them with financial support.

For example, in Paraguay, a new law was passed that would give the government powers to shut down NGOs who fail to comply with additional audits and suspend their directors and staff for up to five years (Blair 2024). It will require non-profits to document the sources and destination of their funding in a government register, but its vague wording could potentially be used to intimidate and silence voices critical of the government, according to critics (Blair 2024).

The Indian tax department also carried out surveys of the BBC offices in Delhi and Mumbai, weeks after they broadcast a documentary critical of the prime minister (Amnesty International 2023). Amnesty International (2023) criticised these, stating that they were ‘raids’ and were ‘an affront to freedom of expression’ (Amnesty International 2023). They further stated that ‘[t]he overbroad powers of the income tax department are repeatedly being weaponized to silence dissent’. In 2023, tax officials also raided the offices of a number of NGOs, including Oxfam India (Amnesty International 2023).

Authorities can also impose more burdensome reporting requirements to exert pressure on non-profits. In 2017, in Romania, parliamentarians submitted a legal proposal that would tighten the regulations of non-profit organisations in the country. This would mean that organisations would need to publish twice a year, giving information on their revenues and expenses as well as details on donors and the activities it was spent on (Benezic 2017). Critics of the proposal stated that non-profit organisations already had the same tax obligations as private entities and that imposing these new obligations was a form of ‘political control’ (Benezic 2017).

Indications that the tax policy and tax authority is being used as a tool for suppression

Despite there being case studies worldwide on tax authorities and tax policies being used to suppress and intimidate civil society actors, identifying when these constitute ‘lawfare’ and when they do not is difficult. With these limitations in mind, and by reviewing the case studies, it is possible to highlight several potential indications that the tax policy and tax authority is being used as a tool for suppression by the government:

|

Indications of suppression |

How to find this information |

|

Unfavourable changes to the tax policy for non-profit organisations during a period where there has been a trend of other legislative or regulatory measures that are hostile towards civil society actors |

Reports on civic space and press freedom, such as those by CIVICUS and Reporters Without Borders, for example. Consultations with local civil society actors and organisations, particularly those that specialise in tax |

|

Cancellation of tax concessions during a period where there has been a trend of other legislative or regulatory measures that are hostile towards civil society actors and independent media or are a mismatch between the measure taken and the problem it purportedly addresses |

Reports on civic space and press freedom, such as those by CIVICUS and Reporters Without Borders, for example. Consultations with local civil society actors and organisations, particularly those that specialise in tax |

|

Changes to the tax policy that would give authorities increased discretion over who should and should not receive tax concessions |

The proposed legislation (if available) to identify the level of discretion given to authorities and reports by/consultations with affected organisations |

|

An investigation into the tax declarations of non-profit actors, independent media, or activists is launched after they have been critical of the government and/or public officials |

While many organisations will not publish this publicly, some may provide a public statement. Otherwise, consultations with organisations that specialise in tax may be useful |

|

A rising trend in tax evasion arrests and convictions of non-profit actors, independent media or activists |

In most countries, the media reports on arrests of non-profit actors. However, these may not cover each instance, in which case consultation with local human rights organisations may be useful |

|

The introduction (or proposed introduction) of foreign agent laws |

The proposal and implementation of these laws are usually reported widely in the media. Statements by and consultations with non-profits that receive substantial foreign funding would help identify the implications of such legislation |

|

Changes to the tax audits of non-profit organisations that go beyond the typical standard of requirement |

The OECD’s study on taxation and philanthropy (2020) provides an overview of what is typically expected from non-profits in terms of reporting requirements in OECD countries (from pages 49 to 57). Other sources of information may include reports from non-profits and the media |

|

Tax measures that result in a significant restriction of the right to freedom of association (which includes the right to access funding) |

The reports of the UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of assembly and of association, or the Council of Europe’s Venice Commission’s guidelines on freedom of association (2014) |

Oversight and accountability in fiscal policymaking

Several reforms and approaches are put forward by the literature that could be considered useful for the oversight of fiscal policymaking and the political use of tax policy. These are generally aimed at government policymaking, judicial oversight and civic society oversight. In countries with a weak rule of law and low levels of democratic accountability, such interventions are likely to be less relevant and effective, making it more challenging to curb politically motivated fiscal policymaking. Consulting international bodies and experts such as the UN (who have advocated against tax reforms that violate human rights law in the past) or the OECD (who works on preventing tax treaty abuse) can provide a point of help and/or advice. In the longer time, improving levels of democracy and governance through building state institutions, the rule of law and strengthen democratic processes such as free and fair elections can also prevent the misuse of tax authorities and tax regulations.

Civil society networks

Several civil society networks exist which help civil society actors who may be targeted by authorities. The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) is a non-profit organisation that promotes press freedom worldwide and mobilises a network of correspondents who report and act on behalf of others that may be targeted (CPJ n.d.). They report on violations in repressive countries, document attacks on the press and provide support to journalists and media support staff around the world with safety and security information and rapid response assistance (CPJ n.d.).

Reporters Without Borders (RSF) provides information about press freedom throughout the world through publishing abuses committed against journalists and forms of censorship (RSF n.d.). Through advocacy, they call on governments, international organisations and decision-makers to denounce any attack on the freedom of information, provide legal support to journalists that are victims of abuse, and train journalists on physical and digital security (RSF n.d.). Finally, the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights provides additional human rights defender protection resources which lists the different organisations that can provide physical protection to human rights defenders or funding. These include Protect Defenders, Front Line Defenders and Freedom House, among others.

Donors to non-profit organisations can also help with capacity building on tax and other matters that non-profits may be targeted for. Where donors are concerned that tax policies and authorities are being instrumentalised, they could support non-profit organisations to maintain transparency and compliance with tax laws, through helping them keep accurate reporting of income, expenses and adherence to regulations governing tax-exempt status if applicable (Ryding 2022:22).

Tax authorities

Tax authorities are typically set up in four different categories, as summarised by the OECD (2024:139):

- a single directorate or unit within the Ministry of Finance or its equivalent

- multiple directorates or units within the Ministry of Finance or its equivalent

- a unified semi-autonomous body, where tax administration and support functions are the responsibility of a commissioner or director general who reports to a government minister

- a unified semi-autonomous body with a board, where tax administration and support functions are the responsibility of a commissioner or director general who reports to an oversight body of management that may include external members; the management board may either be decision-making or advisory

Despite these different arrangements, the OECD (2024:141) reports that most tax authorities report that they have autonomy over their administrative functions. Autonomy includes in the areas of budget expenditure management, organisation, planning, performance standards, personnel recruitment, development and remuneration, as well as in-house ICT systems (OECD 2024:141-142).

In 2010, Crandall (2010:4) argued that there was generally a trend of many governments to increase the autonomy of tax authorities. In terms of the governance and accountability of tax authorities, the author identifies several features that are more common in semi-autonomous tax authorities as opposed to those that sit within a Ministry of Finance:

- in semi-autonomous authorities, the minister of finance has a more limited role, such as the appointment of the board or CEO and limited broad strategic and tax policy directive powers

- boards have powers beyond just advisory and may be able to make legislative and management decisions

- the commissioner general has responsibility for revenue operations with vested powers from relevant legislation

- the reporting requirements may change from being part of the normal government reporting to needing to follow special requirements specified in legislation

- and an external auditor assesses activities rather than the auditor-general (Crandall 2010:9).

However, Crandall (2010) notes that the autonomy of a tax authority alone is not enough to lead to improved effectiveness and compliance, this must also be accompanied with other commitments and plans for reform. Nonetheless, granting more autonomy to these bodies could potentially help shield them to a certain extent from being used for political outcomes such as targeting civil society.

The EU proposes the following nine guidelines which are aimed at top-level-management at tax administrations on how to strengthen trust, created through a project initiated by the Tax Administration EU Summit (EU n.d.):

- Respectful treatment for every taxpayer: Tax administrations’ treatment of taxpayers should be tailored to meet their individual needs, and treatment should be respectful regardless of the context

- Act transparent and predictable

- Use power to strengthen trust: Research shows that actions by a tax administration whether audits, enforcement or recovery actions may have a positive or negative impact on taxpayers’ motivation to comply with their obligations. For example, an enforcement action may be immediately effective but if it is seen as illegitimate or unfair, it may reduce the motivation to comply in the future

- Use communication as a trust builder: Tax administrations should aim for transparency and consistency

- Influence trust through digitalisation: Digital solutions could create a positive experience for the taxpayer, minimise burdens, provide the relevant assurance that taxpayers seek, and this will contribute to building trust which will positively influence voluntary tax compliance.

- Measuring and evaluating trust: understanding the taxpayers’ perception of the Tax Administration, in general, and of its integral parts such as audit, customer care, communication etc. Research shows that in order to build (and maintain) trust, an understanding of the taxpayers’ perception of the Tax Administration and other public sector organisations is needed

- Work proactively and in cooperation: By working together Tax Administrations can gain valuable insights into taxpayer behaviours, the challenges they face and the concerns they may have

- Focus on how organisational behaviour supports trust

- Let your overall trust-based strategy determine performance: A good performance management system sets the goals, objectives and follow-ups to control and support the implementation of the tax administration’s strategy

There are also several networks on tax matters, such as the Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters, the Intra-European Organisation of Tax Administrations and the Network for Better Tax Administration. These networks provide platforms for an exchange of knowledge and ideas between tax authorities and could help build their capacity.

Fiscal rules and fiscal councils

One of the main responses intended to reduce the discretion of politicians in fiscal policymaking has been the introduction of fiscal rules and frameworks to reduce the discretion of politicians (Gaspar, Gupta and Mulas-Granados 2017:10). Fiscal rules provide legally binding objectives for tax policy, which can include limiting changes to the tax policy and mandating independent oversight mechanisms.

For example, the EU requires certain fiscal rules to be in place for its member states. It has recently adopted new legislation to improve its existing framework to ‘safeguard balanced and sustainable public finances, increase the focus on structural reforms and investments to spur growth and job creation’ (Council of the EU 2024). An advisory fiscal board has also been created to monitor implementation of the EU fiscal framework, advise the EC on the euro-area-wide fiscal stance and facilitate coordination among national independent fiscal institutions (Debrun, Gérad and Harris 2016:402). However, the EU’s fiscal rules focus predominately on budget deficits, structural reforms and public investments, rather than constraining the potential political influence of its member states (Council of EU 2024).

Research generally suggests that fiscal rules can be useful in curtailing the politicisation of tax and other fiscal policies. Gootjes, de Haan and Jong-A-Pin (2021) analysed a dataset of 77 democracies between 1984 and 2014, looking at the conditionality of the relationship between elections and budget deficits. Looking at data on fiscal rules which was provided by the IMF, they found that strong fiscal rules constrain political budget cycles. While the authors do not go into tax policy explicitly, their findings about the effect of fiscal rules may also have a bearing on reducing the political use of tax.

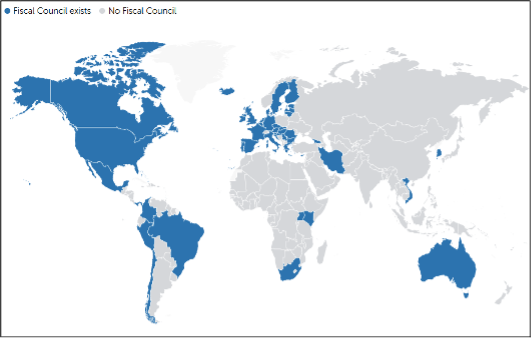

Independent fiscal councils (also referred to as independent fiscal institutions or fiscal councils) have been introduced to provide unbiased information and analysis to monitor governments’ compliance with their commitments and legislated fiscal rules (Gaspar, Gupta and Mulas-Granados 2017:11).

Figure 2: Countries with fiscal councils around the world as of 2021

Source: IMF n.d.

Whether independent fiscal councils can appeal to policymakers and help address skewed decision-making is studied in the research of Debrun, Gérad and Harris (2016). They find that independent fiscal councils can successfully inform voters of fiscal policy and strengthen democratic accountability, and that they are effective in raising concerns publicly. This helps the public reward good policies and sanction bad ones (Debrun, Gérad and Harris 2016). Wyplosz (2013) further argues that both fiscal rules and independent fiscal councils together are needed for successful and accountable fiscal policymaking.

In the UK, for example, fiscal rules were first set in 1997 and were set by the incumbent government and serve as a public commitment that is monitored by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) who evaluates government performance against their targets (Office for Budget Responsibility n.d.). There is also a ‘fiscal lock’ that was included in the Budget Responsibility Act of 2024, which means that fiscally significant decisions should be scrutinised by the OBR (Institute for Government 2020. However, while the OBR provides a level of accountability to the government, it does not explicitly state on its website that it prevents the government from using tax policy and authorities to target certain areas of society. Nonetheless, the oversight body still could potentially have the authority to do so if necessary.

Judicial oversight

Judicial oversight through tax tribunals (also known as tax courts or fiscal courts) help to settle disputes between citizens and tax authorities. They provide fair appeals mechanisms to challenge decisions made, therefore making the independence of these courts important in providing accountability in fiscal policymaking and decisions.

As an example of this process, in Albania, the constitutional court overturned the law on 15% tax for freelancers after a complaint was made by the Democratic Party and civil society (Si 2024). The president of the constitutional court said that this law violated the freedom of economic activity and the principle of proportionality, overturning the law (Si 2024).

And, in 2014 in Germany, a non-profit organisation that was critical of the government’s actions received a letter from the local tax office indicating that its public benefit status had been revoked on the grounds of its involvement in political activities (Poppe and Wolff 2017). The tax office argued that the organisation had pursued activities beyond that of public benefit purposes, citing its campaigns for financial market regulations and a tax on financial transactions. The case was taken to the tax court which ruled in favour of the organisation, confirming the public benefit nature of its work, viewing its political activities as legitimate means to reach its objectives (Poppe and Wolff 2017). There were later appeals by the tax office, however, this case still underscores the importance of independent tax courts which can provide oversight to any decisions made by the tax authorities.

- Several more countries have adopted similar laws since 2017.