Query

Please provide an overview of corruption risks and anti-corruption measures for post-earthquake recovery in Türkiye.

Overview of governance in Türkiye

After the Justice and Development Party (AKP) swept to power in 2002, Türkiye undertook various economic and governance reforms, such as easing restrictions on the media, asserting civilian control over the military and revising the penal code (Hoffmann and Werz 2019). The AKP administration’s apparent desire for deeper engagement with the European Union was formalised in 2005 when accession negotiations began, and for a while the Turkish government continued to take steps to improve the rule of law (Seffaflık 2016: 7).

However, observers note that from 2011 onwards there was a ‘dramatic deterioration of democratic standards’, which accelerated after the imposition of a state of emergency following an attempted coup in July 2016 (Hoffmann and Werz 2019: 14; Seffaflık 2016: 7). In the aftermath of the coup attempt, more than 125,000 public officials were dismissed (Akdeniz and Altıparmak 2020: 39), including around 4,000 judges and prosecutors (UN 2017: 17). Many of the officials removed were reportedly replaced by people with limited experience but close ties to the ruling party (Turkish Minute 2024).

By late 2016, after 14 years in power, analysts were pointing to the ‘formation of a ruling elite within the [AKP] party’ and a consolidation of power in that cadre around President Erdoğan, such that the domineering influence of the executive branch had become the ‘most pressing [governance] issue’ in Türkiye (Seffaflık 2016: 8, 16).

The state of emergency that was imposed after the 2016 coup attempt was lifted in 2018 (Amnesty International 2018). Nonetheless, since then the country has continued to drift towards autocratic modes of governance, facilitated by three factors. First, a package of new security laws transposed into permanent legislation many of the restrictive special powers that had been introduced during the state of emergency (BMZ 2021). Second, the transition to a presidential system in 2018 extended considerable new powers to the president, including the authority to make laws by decree (BMZ 2021). Third, the influx of ‘underqualified pro-AKP personnel’ into the state apparatus since 2016 has reportedly politicised public administration and deprived state institutions of expertise (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2024).

Indeed, in the last five years, the Turkish state under Erdoğan has been characterised by further ‘democratic backsliding’ as the office of the presidency has consolidated ever more power while the legislative and judicial branches have been progressively weakened (EEAS 2023). The Bertelsmann Stiftung (2024) argues that the hollowing out of checks and balances and the associated concentration of power ‘has given rise to a highly inefficient system’, in which overcentralisation leads ‘to delays in decision-making and a lack of coordination among state institutions, especially at the local level’.

Clientelism is widely argued to play a major role in Turkish politics (Arslantaş 2020; Bilgin 2024; Gürakar and Bircan 2018; Tahiroğlu 2022; Yıldırım 2022). The governance model that has emerged under AKP rule is marked by clientelist relationships with favoured firms; pro-government businesses are awarded lucrative public contracts, cheap credit and tax relief, while in return these businesses provide the AKP with ‘campaign contributions, government-friendly media, donations to pro-AKP charities and foundations, and the provision of goods to the urban poor’ (Esen and Gumuscu 2020: 7).

Gürakar and Bircan (2018) argue that the ‘two foremost actors perpetuating the AKP’s clientelist strategy’ have been municipal administrations and the housing development administration (TOKİ). According to the authors, the AKP has pursued a two-pronged approach, by awarding lucrative public contracts to politically connected firms to construct social housing and provide municipal services. In this manner, the AKP has been able to establish a reliable pool of political donors and shore up sources of electoral support among the populace (Gürakar and Bircan 2018).

Esen and Gumuscu (2020: 1) argue that this ‘partisan redistribution’ model has resulted in a ‘new political calculus’ in the country, a blend of populism and crony capitalism that has reduced tolerance of political pluralism or dissent. Indeed, as the rule of law, civic space and press freedoms have come under considerable pressure, some scholars suggest that Türkiye is ‘no longer a democracy [but] a competitive authoritarian regime.’ Others offer a more cautious assessment of the country as a ‘flawed democracy’, pointing out that the tightly contested 2023 presidential elections indicate that the ‘the political system is competitive’ (Dalay and Toremark 2024).

Against this background, commentators have suggested that the devastating earthquakes that hit Türkiye in February 2023 ‘exposed the scale of political and institutional deterioration in Türkiye’ (Aksoy and Çevik 2023; Ertas 2023), especially rampant levels of corruption and maladministration (Cifuentes-Faura 2024).

Box 1: The February 2023 earthquakes

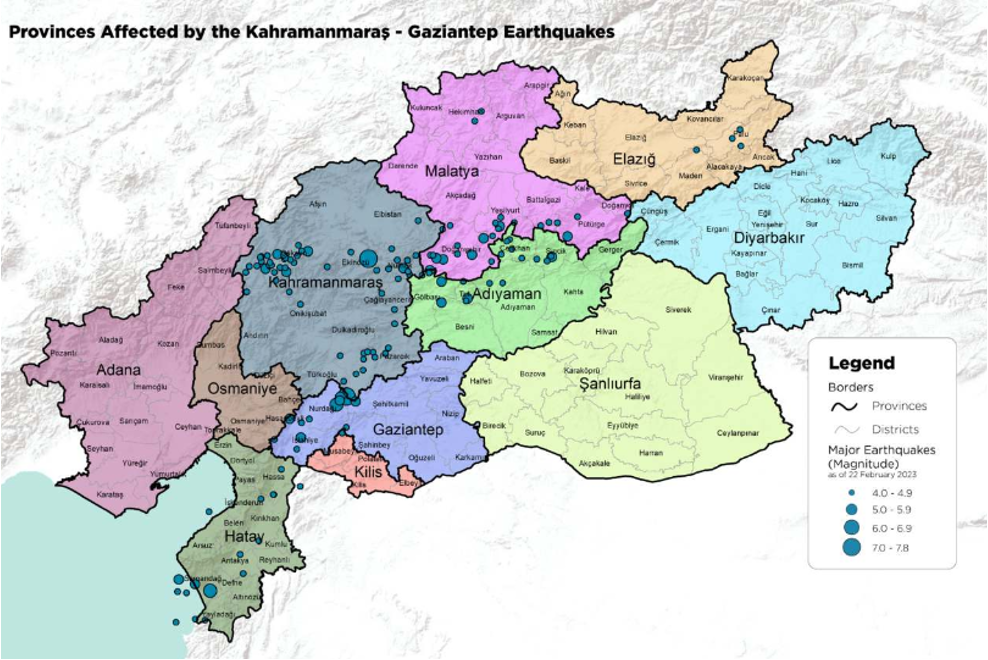

On the 6 February 2023, southeastern Türkiye was struck by two devastating earthquakes, marking one of the deadliest natural disasters in the region's history (Temblor 2023). These earthquakes caused widespread devastation, affecting an estimated 14 million people across 11 provinces in Türkiye, and resulting in the deaths of more than 55,000 people and injuries to a further 100,000. Approximately 1.9 million homes were damaged or destroyed, and 3.3 million people displaced (OECD 2023: 3; World Bank 2024a). The total damage has been estimated to be anywhere between US$34 billion (World Bank 2023a) and US$148.8 billion (Milat Gazetesi 2023).

The aftermath of these earthquakes presents significant challenges for Türkiye, requiring sustained efforts in reconstruction, economic recovery and support for affected populations. As of October 2024, the Turkish government claimed that US$70 billion had already been spent on earthquake relief and rebuilding (Reuters 2024). In 2025, the government plans to allocate a further US$17.05 billion for continued reconstruction efforts (Reuters 2024).

Figure 1: Provinces affects by the February 2023 earthquakes

Source: UNDP (2023: 5)

Observers argue that years of misgovernance both: i) created the conditions for the earthquakes to wreak havoc on the built landscape; and ii) impeded an effective humanitarian response.

First, the view that corruption aggravated poor building standards and contributed to the death toll and physical devastation has been expressed by observers (Bozkurt 2023; Kim 2023; Tol 2023; Ülgen 2023), academics (Cifeuntes-Faura 2024) and local CSOs (Seffaflık 2024a; Seffaflık 2024b). In this account, political clientelism meant that, in exchange for political and financial support, construction companies were allowed to build unsafe structures.

After a previous earthquake in 1999, a special purpose tax was collected to generate revenues for earthquake resilience measures and new construction regulations for earthquake resistant buildings were introduced. Said-Moorhouse et al. (2023) state that it is unclear how the US$38.4 billion raised from the tax was spent, while Özarslan (2023) and Aksoy and Çevik (2023) note that corrupt practices undermined enforcement of the new regulations. Stories collected by Seffaflık (2024a), for instance, illustrate how informal ties between developers, engineers and municipal officials, as well as outright corruption in the construction sector (such as bribery and document falsification) led to the construction of unsafe buildings that collapsed during the earthquakes. Indeed, since the earthquake, several owners of construction companies and officials have been arrested for safety violations and irregularities (Hubbard et al. 2023).

Moreover, due to construction amnesties introduced by the government in 2018, developers were able to receive ex-post legal approval for more than 3 million illegal and potentially unsafe structures in exchange for the payment of building registration fees (Seffaflık 2024b: 4). These amnesties were reportedly introduced to win electoral support, in spite of strong objections from experts and civil society (Samson and Yackley 2023). Indeed, laws passed in 2011 and 2013 ‘specifically excluded […] civil engineers, architects and urban planners from the process of approving and inspecting construction projects’ (Letsch 2023).

Second, the government’s initial response to the disaster faced significant criticism for its perceived slowness and inefficiency, with critics arguing that the centralising tendencies and authoritarian inclinations of Erdoğan’s administration had resulted in a ‘paralysis of the administrative institutions’ and ‘state dysfunction’ (Coşkun 2023; Ertas 2023). In this view, the highly personalised and centralised system of power left state institutions, including the armed forces, unwilling or unable to take the initiative during the crises without explicit instructions from the executive (Aksoy and Çevik 2023). Analysts have also pointed to the erosion of administrative capacity in the decade before the earthquakes, particularly at the disaster and emergency management authority (AFAD).844efacb05fa

Media and civil society landscape

According to the International Centre for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL 2025) there are 100,760 registered CSOs in Türkiye, as well as many more informal organisations. Most of these groups work on social services, education, health, vocational training, sports and religion, with less than 2% active in the field of human rights.

It is mandatory for civil society associations to notify Turkish authorities of grants received from international organisations (ICNL 2025). In October 2024, the government proposed a new foreign agents law, with an article that concerned numerous ‘CSOs and media outlets receiving foreign funding, because their statements, monitoring, and research activities’ appeared to fall within its scope (ICNL 2025).While the article in question was withdrawn in November 2024, the ICNL (2025) expects a revised legislative proposal to be resubmitted to parliament soon.

The EEAS (2023) has expressed concern about shrinking civic space in Türkiye, pointing to recent measures that have restricted freedoms of assembly, association and expression. Authorities routinely prohibit and disperse protests critical of the government (OMCT 2022), leading CIVICUS (2024a) to classify civic space in the country as ‘repressed’. Nonetheless, under growing pressure from government authorities, civil society has continued to be vocal and has played an active role in supporting people affected by the earthquake. Despite the fact that many local organisations were themselves heavily affected by the earthquakes,d470143eeb2f a wide range of civil society groups mobilised rapidly to raise funds and deliver aid, including food, blankets and temporary shelters (LHF 2023). Some government representatives accused some NGOs actively engaged in emergency relief, such as AHBAP, of being ‘political provocateurs’ (Arıcan 2023: 2). A survey of 172 CSOs operating in Adıyaman, Hatay, Kahramanmaraş and Malatya provinces found that only five of them had received any support from the government in the aftermath of the earthquake (STGM 2023).

Reporters without Borders (2024) estimates that more than 90% of Turkish media operates under strict government control, while CIVICUS (2024b) states that independent journalists are frequently subject to government interference in editorial decisions, as well as detention, arrest and prosecution. In 2023, the Media Freedom Rapid Response (2024: 36) consortium recorded over 236 violations of press and media freedoms in Türkiye. Reports of assaults on journalists reporting on corruption are fairly common (MLSA Turkey 2023), while in 2022 a journalist working on a story about corruption was killed (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2024). This oppressive environment has led to self-censorship among media outlets (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2024).

The government is known to monitor and censor the internet, and in October 2022 a law on disinformation came into force that broadened the range of activities on social media deemed to be criminal (Freedom House 2024). In the aftermath of the earthquake, authorities used this new law to detain nearly 80 people for criticising the government’s response to the disaster and initiated legal proceedings against nearly 300 people for the same reason (Freedom House 2024). There are also reports of journalists being obstructed from carrying out their work in the affected provinces (MFRR 2024: 37).

Extent of corruption in Türkiye

In terms of the effectiveness of anti-corruption measures in Türkiye, observers have noted that since the AKP came to power in 2002, there have been two distinct stages. The first phase to approximately 2011 was marked by a perceived reduction in the incidence of corruption, the second phase since then has been characterised by a renewed increase in perceived levels of corruption, reportedly driven by a rise in corruption in public contracting (Cifeuntes-Faura 2024). This impression is corroborated by Türkiye’s performance on the World Bank’s Control of Corruption indicator: the country’s percentile rank rose from 34.9 in 2002 to 61.6 in 2012, before declining steadily back down to 34.9 by 2023 (World Bank 2024b).f4757297e25a

Türkiye adopted several formal anti-corruption measures in the 2000s, partly in response to EU membership requirements (Canveren 2023), and these legal and institutional reforms are thought to have had some effect in reducing petty corruption in public administration (Kimya 2019; Seffaflık 2016: 7). Indeed, by 2016, public services that a decade earlier had been perceived as highly corrupt, such as the police, tax offices and land registry were no longer viewed as being so, which Seffaflık (2016: 9) attributed to the rise in e-government services.

In 2013, corruption allegations emerged implicating members of Erdoğan’s family and cabinet (Letsch 2013). The response of Erdoğan’s government was to obstruct investigations, fire leading law enforcement and judicial officials and ultimately ensure the case was dismissed (BBC 2013; Cengiz 2017; Tattersall and Butler 2014). These events effectively halted Türkiye’s anti-corruption efforts (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2024), with the result that allegations of corruption involving senior officials and politicians are no longer seriously investigated (EEAS 2023: 28; GI-TOC 2023: 5). Türkiye does not have a ‘permanent, functionally independent anti-corruption prevention body’, the accountability and transparency of public institutions is generally low and the coordination between state institutions on anti-corruption matters is poor (EEAS 2023: 27).

Thus, while Türkiye is a signatory to all major international anti-corruption interventions, its implementation and compliance with them is poor. For instance, Türkiye’s enforcement of the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention is non-existent, with no individual or company ever having been held liable for foreign bribery (OECD 2024). The Council of Europe (2023: 1) has pointed to the ‘very low level of compliance’ with GRECO fourth round evaluation recommendations on preventing corruption by members of parliament, judges and prosecutors.

Indeed, grand corruption appears to have become ever more egregious over the last decade (Canveren 2023). Kimya (2019) notes that failure to reform political finance has ‘opened the door for cronyism’ and the emergence of a business-politics nexus in which politically connected firms receive lucrative public contracts. Interestingly, contrary to the experience from other emerging economies, Kimya (2019) concludes that rather than business elites coming to dominate national politics, in Türkiye it is the ruling political party that has consolidated its grip over business groups.

Sectors in which corruption is believed to be extensive include transportation, infrastructure, real estate, utilities, extractive industries (Seffaflık 2016: 9), as well as construction, land administration, local government budgets and political finance (EEAS 2023: 28). The allocation of building permits by municipalities, oversight of public contracting and labour regulation in the construction sector are all areas likely to be affected by corruption (Seffaflık 2016: 9).

Table 1: Türkiye’s performance on selected governance indicators

|

Worldwide Governance Indicators |

CPI |

GCB |

Rule of law |

UNCAC |

Freedom House |

||

|

Control of Corruption |

Rule of Law |

Voice and Accountability |

Rank |

Bribery rate |

Rank |

Status |

Score (of 100) |

|

60.66 42.86 34.91

|

54.46 38.10 32.55 |

40.85 24.76 25.00 |

115 / 180 34/100 |

18% |

117 / 142 0.42 |

Accession 2006 |

33 |

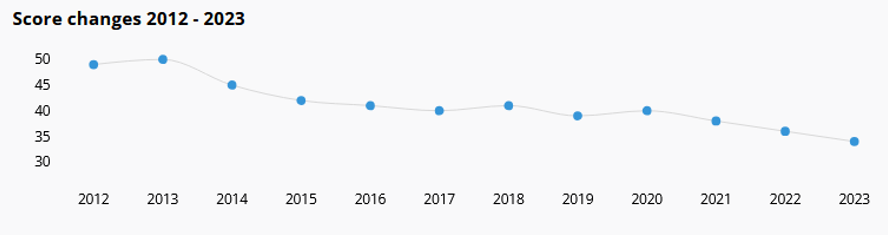

As illustrated in Figure 2, Türkiye’s performance on the CPI has declined sharply by 16 points since 2013, in line with the broader pattern of decline across governance indices in the last decade (International IDEA 2024).

Figure 2: Türkiye’s performance on the Corruption Perceptions Index since 2012

Source: Transparency International (2024).

Local government corruption

Local government in Türkiye can refer to a range of centrally appointed and locally elected politicians and administrators across four categories: special provincial administrations, municipalities, villages and neighbourhoods, each of which has its own institutional form (Ateş 2021: 66).32119f8159d0 For example, municipalities are comprised of (Ateş 2021: 68-72):

- the municipal council: decision-making bodies that produce strategic plans, vote on budgets and take decisions on buying or selling municipal real estate

- the mayor: chief executives of the municipalities who chair councils, approve (or veto) council decisions and appoint municipal personnel

- the executive committee: exercises limited discretion over some areas of spending

Although at the national level the AKP appears to be in control of the state apparatus, the political opposition in the form of the Republic People’s Party (CHP) took power in most major cities as well as in many district level municipalities following the March 2024 local elections (Dalay and Toremark 2024). Nonetheless, in earthquake affected areas, the picture was mixed: the CHP won control of Adiyaman from the AKP, but the AKP won in Kahramanmaraş and Gaziantep and even flipped Hatay province from CHP to AKP control (Kirby and Kasapoglu 2024).

According to the EEAS (2023: 14), the central government has a track record of pressuring local administrations governed by opposition parties, to the detriment of local democracy. For instance, after the previous round of local elections in 2019, 48 mayors in the southeast of Türkiye were forcibly removed from office and hundreds more municipal officials detained on terrorism related charges (EEAS 2023: 15, 19). In addition, the power of the Presidency to pass laws by decree means that the central government is able to redefine the authority of municipal government. Güven et al. (2023: 145) conclude that the relationship between central and local government is ‘fundamentally […] paternalistic and authoritarian’.

Local government has long been seen as having a high risk of corruption for several reasons. First, the traditional model of clientelism between local notables and their clients continues to influence local politics, though party political organisations have come to dominate the distribution of benefits (Ateş 2021: 74). Second, many municipalities essentially ‘operate as local presidential systems’, in which strong mayors dictate the political agenda, maintain strong informal ties with council members that can undermine checks and balances, and use their ability to appoint municipal employees in ways that strengthen their patronage networks (Ateş 2021: 68-72). Third, although oversight mechanisms do exist, these are limited and often ineffective (Seffaflık 2016: 8, 44). For example, although the 2003 Public Finance Management and Control Act mandates the establishment of an internal control system to prevent financial mismanagement, the fact that at the local level internal audit processes are ‘dependent on the mayor […] raises doubts about the[ir] efficiency’ (Ateş 2021: 68-72).

The Turkish court of accounts has criticised the use of public resources and inadequate bookkeeping practices by local governments (Cengiz et al. 2014). A study of irregularities reported by the Turkish court of accounts for municipalities in Turkey between 2012 and 2018 found that (Ateş 2021):

- the total number of irregularities reported increased after 2014, with the most frequent irregularities relating to bookkeeping, public procurement and management of municipal real estate. The author notes that all three are areas that are ‘significantly associated with the risk of public loss and corruption’ (Ateş 2021: 150).

- irregularities in public procurement, as well as incidents of mismanagement that could indicate patronage or corruption, are more pronounced in municipalities controlled by the AKP (Ateş 2021: 139-142).

- reports by the court of accounts detecting irregularities in a given municipality were not associated with a subsequent reduction in the number of irregularities in that municipality, revealing a lack of accountability for maladministration.

- irregularities increased around local elections, suggesting that parties seek to secure electoral support and consolidate political power through irregularities that either affect revenue generation, such as ‘under-collection of taxes, fees or rentals’, or that affect public expenditure, such as ‘irregularities in public procurement [that] unnecessarily increase municipal expenditures’ (Ateş 2021: 150).

Ateş (2021: 154) explains these findings with reference to the ‘clientelism embedded in the political culture that normalises particularistic exchanges […] in Turkish local politics’. According to some reports, when the newly elected CHP officeholders took control of municipalities in Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir after the 2024 local elections, they uncovered financial irregularities on the part of the previous AKP administrations relating to ‘dubious tender processes and misallocated funds’ (Medya News 2024). There is, nonetheless, some indication that patronage networks can survive the change in power from one political party to another (Diken 2025).

Challenges in post-earthquake relief

Coordination challenges

AFAD was established in 2009 through the merger of three existing agencies to improve coordination in disaster management (Ertas 2023). However, there are multiple examples of inadequate coordination between central and local authorities, NGOs and international actors during the initial response to the earthquake. For instance, crisis management centres and provincial first aid committees failed to communicate effectively, provinces run by non-AKP parties were not kept informed by central agencies, and AFAD failed to provide necessary permission to other actors to conduct search and rescue operations (Kavas 2024). In the weeks following the disaster, the coordination of relief supplies was poor, with incoherent recording, storage and distribution of aid sent. This not only meant that some areas, particularly rural locations, were neglected (Kavas 2024), but it also provided opportunities for questionable practices, such as the Red Crescent selling tents and food to other charitable organisations, instead of donating them to people in need after the earthquake (Seffaflık 2024b: 9).

The OECD (2023: 10) points out that decentralised approaches to disaster relief can help ensure the adoption of ‘solution tailored to local needs and priorities’. However, in the affected Turkish provinces, many local governments suffered heavy damage to public buildings and a loss of civil servants, hindering their ability to effectively manage reconstruction efforts and aid distribution (Union of Municipalities of Türkiye 2023).

Numerous local and national NGOs engaged in earthquake relief formed a platform called the Local Humanitarian Forum (LHF 2023) to represent Turkish civil society in UN OCHA’s formal coordination mechanism handling the response to the disaster. The LHF (2023) mapped local CSOs, established partnerships between Turkish civil society groups and donors, UN agencies and international NGOs, as well as channelled relief funding to community groups and local solidarity initiatives.

Similarly, OCHA’s Connecting Business Initiative set up a platform for Turkish companies and TÜRKONFED to coordinate private sector contributions to relief efforts while TÜRKONFED established a crisis desk to manage incoming assistance and provide in-kind support to people in affected provinces (CBI 2024: 7).

Lack of transparency

Access to information relevant for disaster relief and recovery is limited in Türkiye. The country has not published tax expenditure reports since 2018 (İstanbul Planlama Ajansı 2024: 14) and dropped out of the Open Government Partnership the year before (ERCAS 2023). The situation is particularly acute in the in the construction and real estate sector, with no transparency in relation to concessions or building permits. Moreover, there is no central public register of company beneficial ownership that could shed light on the private entities contracted to support recovery and reconstruction efforts (ERCAS 2024). Early reports suggested that no-bid contracts were awarded to construction companies owned by former AKP MPs, parliamentary candidates, spouses, friends and relatives (Duvar English 2023b). TOKİ’s revenue model is opaque, and the organisation is exempt from public auditing requirements (OHCHR 2014).

In terms of the recovery funds for the 2023 earthquake, data on how donations and funds have been allocated has not been made publicly available by AFAD (Article 19 2023). For instance, the lack of clear regulation on how the reported US$6.1 billion in donations for earthquake victims raised as part of the Türkiye, One Heart campaign would be distributed by the AFAD and the Turkish Red Crescent Society has made it challenging to track the funds (AZTV 2023). Civil society groups have called for ‘more detailed information on how donations were spent and a transparent monitoring mechanism’ (Seffaflık 2024b: 9-10).

Seffaflık (2024b: 10) states that some of the contracts signed for the reconstruction of housing were not only signed before needs assessments or ground surveys had been conducted, but that the terms agreed with the companies have not been disclosed. Similarly, RVO (2024: 38) states that central authorities rapidly signed public tenders for debris removal after the earthquake but notes that there is no publicly available information on the process. Michaelson (2024) reported in February 2024 that ‘although construction is evident across a broad swath of the south-east, data on the results is opaque’.

In the private sector, the Connecting Business Initiative developed the Türkiye Earthquakes Private Sector Donations Tracker Dashboard, though the organisation notes that ‘data collection has proven challenging’ (CBI 2024: 10).

Common corruption risk areas in post-disaster recovery efforts

In the aftermath of national disasters, past experience has shown that the combination of a huge influx of financial flows, pressure on government to act swiftly and weakened capacity of local institutions creates fertile ground for fraud and corruption (Fenner and Mahlstein 2019: 241). Actors engaged in post-disaster recovery need to support numerous activities, from procuring goods to transporting supplies, identifying target areas, conducting needs assessments, registering recipients and distributing aid (Carr & Breau 2009: 16). Much of this involves working with independent contractors and local partners, and every stage provides opportunities for corruption.

During the first phase of providing immediate relief, saving lives and restoring basic services, the effectiveness of donors’ interventions can be eroded by aid diversion, bribery and embezzlement (Maxwell et al. 2012). These practices often have a disproportionate impact on the most vulnerable groups. Furthermore, there are non-financial forms of corruption that affect humanitarian interventions, such as nepotism and cronyism in staff recruitment, the skewed allotment of aid to serve political ends and sexual corruption at the point of distribution (Shipley 2019:5; Transparency International 2016a).

Even once the immediate humanitarian crisis has subsided, longer term reconstruction and recovery effortsb0640d4c6be6 to restore livelihoods and rebuild infrastructure are often plagued by corrupt practices. During this phase, corruption risks often stem from ‘improper planning and contracting processes favouring particular interest groups’ (Fenner and Mahlstein 2019: 244).

As such, the OECD (2023: 10) notes that ‘provisions must be made to head off risks of aid flows being captured by vested interests and corruption’. There are salutary lessons where corruption has affected reconstruction efforts in other countries. For instance, in Puerto Rico, reconstruction after Hurricane Maria in 2017 was hampered by clientelism and corruption, such as the electorally motivated allocation of resources, which slowed recovery efforts and harmed local communities (Thompson et al. 2023: 24). Government agencies responsible for reconstruction provided limited transparency, accountability or participation, offering only one citizens’ meeting per year (Masses 2022). Despite billions being dedicated to housing, only 2% of the housing needs had been met by 2022, while private contractors had received multi-million-dollar contracts (Masses 2022).

The following section considers four areas commonly affected by corruption in recovery measures: planning, targeting, procurement and service delivery.

Reconstruction planning and priority setting

There can be both political and technical challenges during the planning phase of recovery and reconstruction efforts. First, emergency powers imposed after the disaster may remain in place for some time and can grant extensive discretion to the authorities (Fazekas 2023). For instance, emergency powers often suspend safeguards such as audit requirements, consultation obligations and the right to information, meaning that there is the risk that officials will use the funds however they see fit with limited oversight (Williams et al. 2022: 4).

At the same time, various interest groups will lobby for different priorities, while government officials may have conflicts of interest that influence their preferred allocation of resources or selection of projects (UNODC 2024). Politicians may promote initiatives that advance their own political causes, such as projects that generate high levels of favourable publicity or divert resources away from areas held by political opponents.

As such, the use of recovery funds can be distorted through corrupt decision-making at the very outset, through doctored terms of reference intended to favour certain entities (Mungiu-Pippidi 2022). For example, measures to support economic recovery often involve grants and flexible loans to affected businesses (Francis et al. 2017). However, opacity and discretion in the allocation of credit or grants to private sector entities creates opportunities for unchecked conflicts of interest, such as local powerbrokers steering credit towards companies in which they have a financial interest.

Therefore, it is commonly stated that an important first step in reconstruction efforts is a robust needs assessment to determine the extent of damage, required resources and appropriate prioritisation (see Box 2).

Box 2: Damage needs assessment in Ukraine

In the context of recovery efforts in Ukraine, experts argued it was vital to gather accurate information on reconstruction requirements locally, geo-tag damaged objects to facilitate verification, validate priorities with various stakeholders (local government, CSOs, businesses and international partners) and compile the information in a public central database (Mungiu-Pippidi 2022; TI Ukraine 2022).

Once the needs assessment was completed, civil society called for a project bank to list all potential reconstruction projects that have been verified as genuine (IZI 2022: 3; Rise Coalition 2022: 7). They suggested listing these projects in order of priority and stipulating that recovery funds from the state budget would be obliged to follow this sequence, whereas other donors could pick and choose projects to finance (Rise Coalition 2022a). The suggestion was for this platform to be linked to Ukraine’s centralised digital procurement tool, so that information on supported projects, funds spent, contractors involved, and project implementation progress could be made public (Rise Coalition 2022). To link transparency to accountability, the Rise Coalition (2022: 10) called for the centralised platform to include a feedback mechanism available to civil society, businesses and donors to report identified violations.

Impartiality and integrity in recovery planning may be difficult to ensure since natural disasters have disrupted pre-existing administrative, legal and financial systems (Maxwell et al. 2008: 9). Administrative records on different population groups could be missing or incomplete, such as census data that could help aid agencies to better understand the needs in different localities and allocate aid accordingly.

Further complicating the issue, consultation with affected (and often displaced) populations may be difficult, which can lead to ‘supply-driven’ rather than ‘demand-driven’ reconstruction planning. This can create additional risks. For instance, the provision of in-kind goods not actually required by targeted populations may decrease constraints on these materials being stolen and sold on the black market (ALNAP 2022: 141).

Finally, in the complex setting of post-disaster recovery, a lack of coordination in the planning phase between multiple donors can obscure subsequent fraudulent practices like ‘double dipping’, where aid recipients, government officials or contractors are paid more than once for a single output (Fenner and Mahlstein 2019: 243).

Situation in Türkiye

Formally, municipalities and special provincial administrations have jurisdiction over land zoning, land acquisition, land assignment, building permits, building and construction regulations (Ateş 2021: 69).b73e20d4bbae However, since the Urban Transformation Act of 2012, central government ministries and TOKİ are empowered to bypass local government bodies to take decisions on urban renewal (Ateş 2021: 83). Moreover, given the fact that local government authorities’ financial resources are generally scarce, regional agencies under the control of central ministries often carry out much of the planning for local governments’ nominal areas of activity (Güven et al. 2023: 145).

In the aftermath of the earthquake, it appears that the central authorities have taken a leading role in reconstruction planning. The Strategy and Budget Office (SBO 2023) of the Turkish presidency produced a post-disaster needs assessment to document the damage and set out a recovery plan for social sectors (housing, education, health), infrastructure (water, municipal services, energy, transport, communications) and economic sectors (agriculture, mining, manufacturing, tourism).

The OECD (2023) cautioned against uncoordinated and overly hasty reconstruction in Türkiye, noting that

‘plans should be made to support the displaced population, including with temporary accommodation, over an extended period. In the aftermath of past disasters, evacuees spent between 5 and 10 years in shelters and temporary housing, requiring temporary services (e.g., schools, hospitals, care facilities) to be maintained for the duration.’

Nonetheless, the central government swiftly announced plans to build hundreds of thousands of new homes in affected provinces within one year (Toksabay and Coşkun 2023), with TOKİ assigned to oversee the work (Elgendy 2023; SBO 2023: 43). Moreover, a presidential decree granted the Ministry of Environment, Urbanization and Climate Change ‘discretion in deciding on places of new settlements and lift[ed] some provision[s] of the zoning law’ (SBO 2023: 211). The SBO (2023: 211) noted that this measure could potentially ‘limit opportunities for participatory processes to ensure that those affected have a say in decisions, or environmental and social assessments’. Concerns about building standards have persisted as experts warned that cities should be re-planned based on scientific data and safety should be prioritised over speed (Article 19 2023; Caglayan and Sezer 2023; Daragahi 2023). TOKİ has also been criticised by CHP politicians for prioritising the construction of luxury, high-priced houses in some affected regions and for not publishing details about how many houses have been constructed so far (Ari 2023).

In 2023, the government passed a law establishing the disaster reconstruction fund (DRF) to manage the allocation of financial resources for zoning and infrastructure in areas affected by the earthquake. The SBO (2023: 211) emphasised that ‘public oversight is important’ in the operation of the fund. However, the EEAS (2023: 22, 77) notes that the law ‘lacked details on the decision-making process, and on the transparency rules for managing the fund’, and expressed concern that the DRF is excluded from the general budget, outside the audit scope of the court of accounts and does not clearly state procurement principles to be used for expenditure.

Past experience indicates the risk of politicised resource allocation during the recovery planning process. Çınar (2016), for example, has shown how provinces that demonstrate electoral support for the AKP are strongly associated with better quality public infrastructure, while Kemahlıoğlu and Özdemir (2018) also conclude that AKP-governed metropolitan municipalities receive more resources. The EEAS (2023: 18) reports that local residents in Diyarbakir have been prevented from participating in the planning of the area’s reconstruction.

The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development has provided 800 EUR million to private sector projects in the earthquake-affected region (Bloomberg HT 2024), including the provision of low-interest loans and credit to local businessowners, channelled through local banks (QNB 2023; Akbank 2023). Ensuring transparency and oversight in the use of this kind of support to local businesses will be important to ensure that the funds do not end up reinforcing existing clientelist networks.

Beneficiary identification and targeting

Once priorities have been established during the planning phase, resources officially allocated for a specific purpose are still at risk of being diverted and misused. Transparency International (2014: 84) points out that the diversion of recovery aid can be either systematic and pre-planned or opportunistic on the part of individuals involved.

The impartiality and needs-driven targeting of assistance in post-disaster settings can be undermined by donor organisations, national and local authorities, and community gatekeepers, each of whom may attempt to influence the allocation criteria and distribution patterns for political reasons (Haver and Carter 2016: 26). In settings in which electoral politics are playing out, a specific dimension entails the undue influence of local political functionaries, who may attempt to direct aid to party members and clients (Khair 2017: 214-215). In addition, aid agencies may come under pressure to hire certain individuals, and local staff may prioritise their kinspeople in employment opportunities (Carr and Breau 2009: 16).

Needs assessments are vulnerable to manipulation by host governments, who have been known to demand amendments to the data and to prevent the publication of the results of the assessment (Steets et al. 2018: 62). An evaluation of the humanitarian response to a drought in Ethiopia found that incentives existed among local leaders to both inflate the number of affected people identified in needs assessments to secure more resources as well as to underreport the scale of the crisis to demonstrate the apparent effectiveness of local leaders in dealing with the crisis (Steets et al. 2020). Community gatekeepers and local elites may also try to manipulate needs assessment by providing inaccurate data ‘to exclude or include certain populations […] due to political, religious, ethnic, tribal or clan or personal affiliations’ (Shipley 2019: 6). Poor targeting can result in oversupplying or undersupplying assistance to intended beneficiaries, which can drive corrupt practices such as embezzlement, extortion and the registration of ‘ghost beneficiaries’ (Fenner and Mahlstein 2019: 243).

Once a needs assessment has been conducted, potential recipients of aid need to be identified and prioritised. Again, this provides ample scope for undue influence by various players (ALNAP 2022: 101). An evaluation of the World Food Programme documented numerous instances of government interference in amending aid agencies’ lists and drawing up alternative lists (Steets et al. 2018: 63). Maxwell et al. (2008: 9) state that a proportion of the aid might be diverted by local strongmen in exchange for allowing the remainder to be delivered to the intended beneficiaries, while intermediaries may insist on the inclusion of family or community members on recipient lists.

In Afghanistan, Mozambique, Somalia and Yemen, ALNAP (2022: 107-108) states that community leaders and local elites have also been complicit in introducing intentional biases into the process of drawing up recipient lists and demanding the final say over which individuals receive aid. In Somalia and Yemen, community power holders have been shown to interrupt the distribution process to prevent it disrupting existing patronage networks (Haver and Carter 2016: 12). In response, aid recipients in some focus group discussions recommended that aid agencies cut out ‘community leaders’ altogether and deal directly with intended beneficiaries (ALNAP 2022: 108). In any case, clear communication of eligibility criteria is important; in Syria, a failure to convey who was entitled to cash support led to rumours on social media and community mistrust of targeting choices (World Food Programme 2021).

There is some suggestion that women and girls are disproportionately affected by corrupt abuses of power in the process of drawing up lists of recipients. A study of humanitarian aid in the DRC found that aid workers demanded both cash and sex from intended beneficiaries in exchange for inclusion on the list of recipients (Henze et al. 2020: 24).

Situation in Türkiye

There is ongoing uncertainty about the true number and exact location of target populations in regions affected by the February 2023 earthquakes, especially with regard to Syrian refugees (see Box 3).

Writing in Foreign Policy, Mart and Tas (2023) argue that in recent decades ‘urban transformation projects [have] became a tool for the ruling party to displace and dispossess minority communities’. They point to the government’s ‘track record of using post-disaster reconstruction for profit’ by charging displaced earthquake victims more than twice the construction cost of new homes after the 2011 earthquake in Van, which mainly affected Kurdish communities. Under Law 6306 introduced in 2012, the Ministry of Urbanization has rights relating to ‘improvement, evacuation, and renewal […] in areas at disaster risk’, which Mart and Tas (2023) allege has been used to target and evict minority groups.

Since the 2023 earthquake, there are some reports that local officials have engaged in politicised targeting. The chair of the Turkish medical association noted that authorities provided additional healthcare services in districts that had previously voted for the AKP, whereas other multicultural areas such as Hatay, İskenderun, Samandağ and Antakya did not receive the same level of medical support (Duvar English 2023c). These districts have sizeable Arab-Alawite, Jewish and Christian communities that do not tend to vote for the AKP. In Adana, the authorities reportedly seized vehicles that had been sent by an opposition political party and that contained aid for earthquake victims (Duvar English 2023d).

Box 3: Refugee populations in Türkiye

Türkiye hosts a large population of Syrian refugees, many of whom lived in areas affected by the 2023 earthquakes. The OECD (2023: 5) states that in the eleven provinces affected by the earthquake, refugees accounted for 14% of the population, compared to the national average of 4%.

However, these figures are likely an underestimate. While local authorities in Türkiye have records of registered refugees in their districts, there are also large numbers of unregistered refugees. As these people tend to avoid contact with authorities, the true number of unregistered refugees is not known. Although registered refugees face restrictions on their ability to move between provinces in Türkiye, many of them left the affected areas after the earthquake (OECD 2023: 8). Finally, after the fall of the Assad regime in December 2024, significant numbers of Syrian refugees in Türkiye began returning to the country of origin via border crossings in Hatay province (Gazete Oksijen 2024). These factors make it difficult to ascertain the true number of affected people and therefore the quantity of potential beneficiaries in different areas, and imply that some kind of refugee population survey would be useful to guide choices in recovery programming.

Procurement

When supporting reconstruction efforts in the aftermath of natural disasters, aid agencies are likely to procure a wide range of goods and services from local suppliers and face constraints on their ability to oversee and audit these contracts. Furthermore, pressure to rapidly rebuild infrastructure and restore livelihoods can lead to local authorities and development partners suspending standard procurement procedures and watering down integrity safeguards, such as competitive bidding and transparency in contract allocation (Fenner and Mahlstein 2019: 243).

Fazekas (2023) lists four types of deviations from standard procurement procedures in response to emergencies:

- spending changes (in procurement spending volume, speed and composition, loans, subsidies)

- organisational changes (new powers given to a public body)

- modified rules and regulations (such as emergency clauses in public procurement that negate the need for open competition)

- changes to laws and law-making (bypassing parliament)

As a result of these kind of changes to standard procedure, integrity risks in procurement may be heightened in reconstruction, including manipulated tender specifications, collusion between bidders, kickbacks to awarding authorities, embezzlement during contract implementation, falsification of receipts and other fraudulent practices and poor record-keeping (Maxwell et al. 2008: 15; Shipley 2019: 6).

The result of corrupt practices in procurement could include the delivery of poor quality or unsafe projects as unscrupulous suppliers cut corners and use low grade materials such as diluted cement or expired medicines and foodstuffs to increase their profit margin (Fenner and Mahlstein 2019: 245; Loosemore et al. 2021). In addition to the reduced quality of goods and services, other potential results include artificially inflated prices and the biased allocation of resources (Schultz and Søreide 2006: 8).

Situation in Türkiye

There are serious concerns about the integrity of public procurement in Türkiye (EEAS 2023), with public contracting having become a tool by which the political class disburses largesse to maintain political support.

Since the Public Procurement Law No. 4734 entered force in 2003, it has been subject to nearly 200 amendments, many of which have ‘weaked[ed] transparency in tenders’ and ‘introduced exception clauses that increased the discretionary power of public authorities’ (Ateş 2021: 77; İstanbul Planlama Ajansı 2024: 9), changes that have made it relatively straightforward for officials to award contracts to their clients. By 2014, the government had reportedly ‘distributed $500 billion worth of contracts without bureaucratic or judicial review’ (Tahiroğlu 2022: 5).

This tendency appears to have increased in recent years, despite the introduction in 2021 of the requirement to submit tender proposals exclusively via an electronic public procurement platform (e-KAP) (Kılınç 2024). A recent study published by İstanbul Planlama Ajansı (2024: 8) found that, across Türkiye, the share of public goods and services purchased through open tender procedures fell from 74.6% in 2015 to 46.7% in 2023, while negotiated tendering rose from 7.9% to 36.3% in the same period. The shift towards negotiated tenders, characterised by bargaining after initial offers, can create opportunities for favouritism and corruption.

This trend has been especially evident in the construction sector, where certain firms with deep ties to the AKP are referred to as ‘the big five’ (Al-Monitor 2022; Michaelson 2024), resulting in what observers have referred to as a ‘construction rentier system’ (Aksoy and Çevik 2023: 2). Indeed, these companies are among the top ten companies globally in terms of the number of public tenders they have been awarded (Özçolak 2022; Samar 2018).

This is equally true at the local level. Among other things, the numerous amendments to the public procurement law allowed municipality-owned enterprises to bypass competitive procurement procedures in public contracting (Seffaflık 2016: 44). Analysis by Gürakar and Bircan (2018: 90) has shown that politically connected firms won 65% of all municipal contracts in cities governed by the AKP from 2004 to 2014, as opposed to around a quarter of contracts in non-AKP cities. This observation is even more pronounced in relation to TOKİ contracts: across Türkiye, 71% of all TOKİ investments were contracted to politically connected firms, which rose to 90% in cities in which the AKP had been in control for the previous three electoral periods (Gürakar and Bircan 2018: 90).

These relationships appear to be deeply embedded at the local level, where ‘the AKP government seems to use public procurement to finance local politics’, and where many politically connected firms ‘have owners/shareholders actively working as the AKP cadres, such as the provincial party leaders or municipal council members’ (Gürakar and Bircan 2018: 91).

Post-earthquake reconstruction and recovery is being handled by many of these same actors (RVO 2024: 25). As a result, donor-funded recovery projects will need to be keenly sensitive to well-established political economies, specifically the existing ties between local politicians, businesspeople and intended beneficiaries. Local officials may view reconstruction and recovery initiatives as an opportunity to reinforce underlying patron-client relationships, including vis-à-vis the ‘urban poor as the receivers of aid in the form of charitable work at the local level’ (Gürakar and Bircan 2018: 91).

In terms of procurement processes for contracts to construct public buildings that were damaged in the 2023 earthquake, Seffaflık (2024b: 7) notes that many of them were marked by procedural shortcomings, such as numerous contracts awarded to a single company and the non-competitive nature of the process. In Antep, for instance, Sendika (2023) reports that a firm belonging to an AKP politician received 193 public contracts between 2010 and 2023, worth a total of 56 million Turkish lira, typically with only one or two suppliers applying for the contracts. Despite the politician being the chair of the zoning commission, five buildings that his firm constructed in the Nurdağı district municipality collapsed during the earthquake (Gerçek Gündem 2023).

These patterns appear to continue to affect the reconstruction process as Turkish authorities adopted emergency procurement provisions allowing deviations from the stipulations of the Public Procurement Law. Less than a month after the disaster, the government had already signed no-bid contracts ‘for reconstruction of 400,000 buildings […] with companies close to the government without conducting thorough geological surveys’ (Colella 2023; Daragahi 2023). Seffaflık (2024b: 10) states that as part of negotiated tenders conducted by TOKİ in late February 2023, not all potential suppliers enjoyed equal access to information about the tender. Moreover, information about the companies and the value of the contracts was not publicly disclosed, which makes subsequent auditing difficult (Toker 2023). Further complicating oversight is the fact that, according to the court of accounts, some large public contracts such as those issued by the Ministry of Transport and Infrastructure are not even notified to the public procurement authority (Gazete Duvar 2022).

It is not only public institutions that are affected by a lack of integrity in procurement. An investigation into the provision of cross-border humanitarian aid from Türkiye to Syria by the USAID office of the inspector general (2019: 5) found evidence of corrupt practices and procurement fraud affecting numerous Turkish suppliers including bid-rigging, kickback schemes and the use of shell companies. The scheme involved collusion between Turkish vendors and procurement staff working at four NGOs operating in southeast Türkiye.

It is important to note that goods, services and works that are funded with foreign financing are excluded from the scope of the public procurement law and thus not subject to its provisions (RVO 2024: 20). As such, where foreign investments, loans or grants are involved, registration on e-KAP is not required. In the case of earthquake recovery, it appears that many foreign agencies are applying their own specific procurement procedures, even where they enter into contractual arrangements with local and national authorities (RVO 2024: 20). As such, where foreign partners involved in recovery efforts insist on applying their own procurement standards, some of the deficiencies of the Turkish procurement system mentioned above may not apply.

Service delivery

Corruption can undermine efforts to restoring the provision of services, including in:

- social sectors such as health and education

- utilities like water and sanitation, energy, transport and communications

- municipal services like waste management, land administration, identification documents, police and fire brigade, and care centres for elderly people, persons with disabilities, youth and women.

Natural disasters can deepen power asymmetries between local communities in need of support and the public officials tasked with providing assistance, thereby heightening risks of coercive corruption, such as demands for bribes or sexual acts in exchange for access to much-needed goods and services. Fenner and Mahlstein (2019: 243) suggest that this can lead to a vicious cycle, as intended beneficiaries turn to illegal activities to be able to afford the illicit fees being demanded by dishonest officials. They also note that the power imbalance between affected communities and those providing aid can mean that aid recipients are less willing to challenge unethical practices for fear of being cut off from essential services, lessening the demand for accountability from below.

Moreover, the pressure to support vulnerable populations during recovery may lead aid implementers to prioritise the provision of tangible goods and services over allocating resources to accountability and control mechanisms (Ardigó and Chêne 2017). Further complicating accountability in restoring services in post-disaster settings is the complex web of institutions involved, both public and private, foreign and domestic. A lack of oversight and downward accountability is likely to reduce constraints on crimes such as embezzlement of resources intended to support recovery, the misuse of materials such as vehicles for private purposes, and the fraudulent inflation of expenses (Fenner and Mahlstein 2019: 245).

Box 4: Delivery partnerships with NGOs

Especially where confidence in the integrity of local public officials is low, development agencies may choose to partner with local NGOs to deliver goods and services to needy populations. The evidence is mixed in terms of whether channelling aid via NGOs increases or decreases corruption risks. Empirical studies indicate that aid recipients may consider NGO staff to be less corrupt than government officials (Baldwin and Winters 2020). Slim (2021) concurs, though notes that many local NGOs ‘operate on personal preference and political network more than they do by professional conduct’. As an example, he alleges that several national societies of the Red Cross and Red Crescent network function as ‘hereditary family firms’, while others are ‘run by political cliques’ (Slim 2021).

Specific corruption risks related to contracting with local NGOs relate to the partner selection process, which could be unduly influenced by kickbacks to aid agency staff or offers of employment (Shipley 2019: 6). Particularly in conditions of remote management where aid agency staff have been withdrawn from the field due to security concerns, it can be difficult for them to assess the performance and integrity of local NGOs. In addition, NGOs may have incentives not to report integrity breaches, especially where they fear losing funding as a result (Darden 2019).

Situation in Türkiye

Ateş (2021: 76) describes municipal administrations as ‘local service providers designed by the centre, not […] as units of bottom-up participation or deliberative democracy’. Other academic research likewise points to the continued ‘discretion of central government in local governance’ and limited public participation in local government (Tan 2018).

The Türkiye Earthquakes Recovery and Reconstruction Assessment, developed by the Strategy and Budget Office (SBO 2023: 77) of the Turkish presidency, states ‘the recovery vision for municipal services is to restore local governments to at least a pre-earthquake level of accountable and efficiency service delivery’.

Despite these ambitions, there have been documented instances of corrupt practices affecting recovery efforts. For example, there are allegations of the misuse of resources sent to assist people affected by the earthquake. For instance, reports from Gaziantep suggest that earthquake relief sent by philanthropic organisations to municipalities was stored for 13 months by local authorities and then distributed for political purposes shortly before elections (Gaziantep Sabah Gazetesi 2024). Similarly, CHP officials in Boğazlıyan municipality accused AKP officials there of hoarding in-kind relief supplies and using these as ‘election bribes’ (ANKA Haber Ajansı 2024). In Antep, equipment donated by citizens such as generators and electric heaters were taken to a factory belonging to the AKP provincial chair, where it was apparently kept until September 2024 (Ari 2023). Perhaps most notoriously, the Red Crescent (Kızılay) has been accused of selling tents and food to other humanitarian associations, instead of donating them to people in need (Agirel 2023; Merkezi 2023; Seffaflık 2024b: 9).

Anti-corruption measures for development partners supporting disaster recovery efforts

Anti-corruption safeguards

Given the risk that funds provided by development partners are misused or diverted, and the implications of this on the speed and quality of recovery, it is important to establish robust financial safeguards to ensure that assistance is delivered in line with the principles of transparency, accountability, participation and objectiveness. This is recognised by the Turkish authorities; the Türkiye Earthquakes Recovery and Reconstruction Assessment (TERRA) pledges to (SBO 2023: 119):

‘establish transparent procedures for the management and exercise of the resources received from the public budget, international funding and donations for the efforts to be carried out in earthquake-affected regions as well as in other provinces, and provide the public with regular information.’

Nonetheless, observers have argued that development partners should ‘prioritise working with local authorities and actors rather than the central state institutions’ (Aksoy and Çevik 2023: 6). In fact, the first tranche of World Bank assistance was targeted at municipalities to support them rebuilding basic infrastructure, rather than provided to central government (World Bank 2023b).

However, it is difficult to entirely bypass central government. The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, for instance, is providing 500 EUR million of funding for reconstruction of water and sanitation facilities in the earthquake zone in 2024 and 2025. While the funding is allocated to the municipalities through the Bank of Provinces, the contract was signed with the Ministry of Treasury and Finance (Bloomberg HT 2024).

Regardless of the level of government that a development partner decides to support during post-disaster recovery, it is important to understand the nature and quality of anti-corruption safeguards that the public institution has in place. According to the UN (2023: 10-11), these include:

- the timely provision of relevant information related to recovery and reconstruction efforts, both across government and to external actors

- the development of risk management systems and protocols, including corruption risk assessment tools

- formal policies for staff on financial disclosure, codes of conducts and conflicts of interest

- the existence and availability of beneficial ownership information for any commercial entities engaged in a contractual relationship with public bodies

- coordination platforms among government entities responsible for recovery projects, as well as the investigation of incidents of fraud or corruption affecting these projects

- the presence of internal and external audit systems to monitor the allocation and distribution of resources intended to support reconstruction and recovery

- the establishment of grievance and reporting mechanisms to allow people to alert competent authorities of wrongdoing and protect those disclosing information

Further information on these points is provided in the following sections, with a focus on the potential contribution of development partners.

Transparency in allocation of funds

Providing accurate and timely information to the public is essential for development agencies to secure trust and facilitate coordination with other actors, including local government bodies, other donors and NGOs on the ground (Jenkins et al. 2020).Especially in disaster relief operations in which normally stringent procedures have been temporarily suspended, operating as transparently as possible can help donors and affected communities identify and mitigate corruption, as well as hold aid implementers to account for delivery (Transparency International 2014). Development partners can also urge aid-recipient governments to use transparent budgetary tracking tools to monitor relevant public spending (Jenkins et al. 2020).

Three aspects of aid transparency are considered particularly important (Development Initiatives 2017):

- traceability: being able to ‘follow the money’ through the chain of transactions from donor to affected communities

- totality: all relevant resource flows from the whole range of stakeholders involved, including both humanitarian aid and longer-term development assistance

- timeliness: providing an up-to-date picture of the resources available is essential to support real-time tracking

In addition to financial data, donors are also encouraged to publish their activity plans and clearly link their spending commitments to stated desired outcomes. As the UNODC (2020) points out, the use of clear, objective and transparent criteria to identify intended beneficiaries is crucial to reduce the risk of corruption that can arise where those responsible for delivering aid enjoy a high level of discretion in selecting recipients. Development agencies should ensure that those eligible for assistance are made aware of the nature and level of support they are entitled to and the method by which this will be delivered (Fenner and Mahlstein 2019: 248). Online platforms, social media and community radio may be valuable channels to communicate this information.

Corruption risk assessment and management

Corruption risk management is a set of procedures that involves systematically identifying, assessing and mitigating potential incidents of fraud or corruption, as well as the continuous monitoring of emerging risks. It operates at the intersection of external risks, such as fraudulent partner organisations and background societal corruption, and internal practices related to administrative processes and delivery mechanisms (Jenkins 2016). While such approaches are unable to completely eliminate the risk of corruption in development projects, the rigorous use of risk management tools has the potential to reduce graft and fraudulent use of donor money.

Johnsøn (2015) provides a useful elaboration of a corruption risk management model, which progresses through four steps:

- Identification: hazards to the project’s outcomes, or reputational or fiduciary risk to the donor need to be identified, and tolerable levels of risk decided upon. Establishing this ‘risk appetite’ is crucial as, during the project’s execution, risks that cross these thresholds will trigger the escalation of avoidance or mitigation measures.

- Assessment: a risk assessment exercise is conducted to determine the significance of identified risks. A common means of establishing risk level is to compile a risk matrix, in which the probability that the risk will materialise is multiplied by the severity of its potential impact. This method allows staff to prioritise risk management actions during the implementation phase of the project.

- Treatment: during this step, staff determine which identified corruption risks require active mitigation. Unacceptably high risks (those which are both likely and serious) need to be treated to bring them below the established risk tolerance levels for each type of corruption risk such as bribes, procurement fraud and embezzlement by donor or partner employees.

- Monitoring: once a project is underway, it is necessary to systematically monitor actual risk levels to evaluate whether further risk mitigation is necessary. Where action is required, the most cost-effective means of resolving the risk should be employed.

Numerous guidelines for corruption risk assessment tools and risk management models have been developed for development agencies. In addition to guidance by Johnsøn (2015), the U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre (2023) has compiled resources on corruption risk management for development agencies, and Transparency International (2014) has issued a handbook to assist risk assessment in humanitarian settings, while USAID (2009) has compiled a useful list of diagnostic guides organised by sector. These materials should be used in conjunction with document reviews, interviews and focus groups with major stakeholders to develop a robust anti-corruption strategy.

Other materials deal specifically with corruption risk management in the context of natural disasters or working with local governments. The World Bank’s (2022a) Disaster Resilient and Responsive Public Financial Management Assessment Tool (2022), although designed for central finance agencies, can be a useful reference point for development partners supporting aid-recipient governments to recover from disasters. It covers risk assessment in relation to planning and budgeting, public investment and asset management, budget execution and control, public procurement, as well as audit and oversight (World Bank 2022a: 2).

Finally, a recent UNDP (2024) publication, Methodology for Corruption Risks Assessment in the Activities of Local Self-Government Bodies, is intended to generate evidence that can be used to reduce corruption risks in the operations of municipal bodies. The document covers key sectors such as urban planning, land resources, management of communal property, public procurement and social-economic infrastructure.

Due diligence of partners

The presence of intermediaries, implementing partners and private sector contractors are common features of contemporary responses to disaster relief and recovery (International IDEA 2016). As such, due diligence of business partners and implementing organisations is an important preventive measure (Shipley 2019).

Due diligence refers to a set of criteria and a suite of analytic practices to appraise the level and type of risk to which an organisation could be exposed through an association with another business entity (UNSDG 2019). Due diligence should assess the background and reputation of a partner, obtain their registration details and confirm their track record and assess their ability to implement the planned project. The approach should be risk-based, with development agencies conducting more in-depth due diligence for partners presenting higher risks.

Conducting robust due diligence on potential suppliers is important to ensure that ownership structures are clarified to the extent possible. This can help reveal any links to public officials, questionable corporate entities or designated organisations. Such information might be gathered by obtaining references and conducting desktop research, though the absence of a central public register of beneficial ownership data in Türkiye may complicate this process (ERCAS 2024).

The UK Department for International Development’s (DFID 2019) developed a due diligence guide to assess potential partners across four pillars. In addition, Transparency International has developed an internal step-by-step guidance on ensuring the integrity, transparency and efficiency of grant mechanisms for local CSOs in humanitarian settings, in line with the EU’s practical guide on contract procedures for European Union external action. The guidance is available on request and includes considerations related to vetting mechanisms and selection criteria when partnering with local NGOs.

Robust procurement and sub-granting procedures

While standard procurement procedures may need to be relaxed during the immediate humanitarian relief phase, these should be progressively re-established as the focus shifts to longer term reconstruction and recovery. Based on a review of the literature, Jenkins et al. (2020: 28-29) suggest that development agencies maintain certain minimum standards in their own procurement processes, such as:

- include experienced procurement staff in emergency response teams

- continue to maintain a separation of duties in finance teams and tender evaluation committees to prevent conflicts of interest that can result in corruption

- where procurement staff are granted some additional freedoms, such as the ability to solicit quotes orally and shorten application deadlines, set clear limits on the use of emergency non-competitive processes

- develop a single (preferably digital) platform

- continue to issue contracts and document transactions, as well as document exceptions to standard procedures, even after contracts are signed

- include anti-corruption clauses in contracts

- where pre-approved lists of suppliers and partners are available, use these to procure goods and services from suppliers with established track records and experience in disaster response

- solicit as many offers as possible and involve at least two people in evaluating these offers

- collect as much high-quality data as possible on suppliers and prices during the tendering stage, and use this to develop cost benchmarks to deter and detect corruption or price gouging

- publish all contracts in full, open data format, including names (and where possible beneficial owners) of companies awarded contracts, as well as terms of payment, delivery and value

- encourage civil society to monitor procurement procedures and facilitate public scrutiny

- set aside designated resources to conduct spot checks on the quality of goods and services

- publish information on expected outputs of contracted services and evaluate delivery outcomes

For specific guidance on mitigating corruption risks in emergency procurement processes, see Schultz and Søreide (2006), European Commission (2011), Williams et al. (2022), and Fazekas and Nishchal (2023).

Internal and external audits

Whether carried out internally (by qualified, impartial staff), externally (by specialist independent audit institutions or firms) or socially (by the community), audits help ensure that an organisation is complying with its own policies, procedures, standards and code of conduct. Audits are important means of promoting transparency and accountability.

While audits are often thought of as just financial checks, an audit is any systematic review to ensure that an organisation is fulfilling its mission and safeguarding its resources. In a well-audited programme, corruption is more likely to be exposed, allowing both rectification and the improvement of existing safeguards. The knowledge that all programmes will be audited can serve as an important deterrent to corrupt behaviour (Transparency International 2014: 39).

Development agencies can earmark funds in their programmes for thorough ex-post audits and widely communicate this decision to deter wrongdoing. As audits rely on a paper trail to track the movement of funds and the use of procured goods and services, development agency country offices should appoint a records custodian and specify a clear records retention policy (Transparency International 2014: 40).

In addition to conducting thorough audits of their own programmes, development agencies should encourage governments to make data on the use of recovery funds available to external auditors, particularly in high-risk areas like health, public procurement, infrastructure and social security expenditures (Transparency International 2020). It is important to note that community led audits will require full access to project information to determine whether the resources expended have reached their intended beneficiaries.

Complaints mechanisms

An increasing number of development agencies are taking steps to protect staff, partners or aid recipients who report corruption or misconduct from retaliation (Shipley 2019: 11). Complaints mechanisms provide affected communities and potential suppliers with channels to report any incidence or suspicion of corruption or other malpractice (Transparency International 2016b). A properly functioning corruption complaint mechanism increases the chances of detecting instances in which corrective action needs to be taken to safeguard funds. Transparency International (2016: 5-9) has provided guidance onestablishing effective community complaints mechanisms.

Transparency International (2014: 52, 139) states that affected communities should be made aware of complaints mechanisms, how they operate, how to file grievances, the investigation process and potential outcomes. Various channels can be established, including complaints boxes and hotlines. In Uganda, for instance, UNHCR has set up a feedback, referral and response mechanism that provides a helpline and call centre for refugees to raise concerns and report corruption, violence, sexual assault and other wrongdoing (Komujuni & Mullard 2020).

Reporting by government staff is also important for uncovering corruption, fraud and misconduct. It is recommended that every public agency have an internal whistleblower system(Terracol 2022). Unfortunately, the OECD (2024) has noted that Türkiye has so far ‘failed to implement a recommendation to protect whistleblowers’, making it even more important that development partners establish safe reporting channels.

Box 5: Digital tools

Digital tools can help to enhance participatory, accountability and transparency in recovery and reconstruction.9a4ea56b36cf

Risk intelligence software: development agencies can use open-source datasets or proprietary software as part of due diligence processes to identify which partners and counterparties have potential conflicts of interest, or money laundering and terrorist financing risks.

E-procurement: whether development agencies procure their own goods and services or work through national partners’ procurement systems, the OECD (2021: 6) encourages them to use e-procurement platforms. These can help capture transactional information and help improve access to all records to auditors and oversight bodies. Data analytics can also amplify the anti-corruption potential of e-procurement systems, such as automatic recognition of corruption ‘red flags’ (Williams et al. 2022).

Existing digital infrastructure: During needs assessment exercises with local partners, development agencies could draw on existing digital infrastructure, such as the Yerel Bilgi system in Türkiye, which captures data such as municipal budgets, employees, vehicle fleet, population statistics and so on (Turboard n.d.). Yerel Bilgi was used in the immediate response to the earthquake to collect information on affected municipalities (SBO 2023: 213).

Blockchain: in principle, distributed ledger technology can create transparent and tamper-proof records of aid transactions, including cash transfers, procurement contracts and supply chain management. This could assist with record-keeping and anti-fraud safeguards. However, a recent literature review found that to date only a few pilot programmes have been deployed in the field and limited empirical evidence exists regarding the real-world application of the technology (Hunt et al. 2022). Zwitter and Boisse-Despiaux (2018) also point to blockchain’s ‘potential to perpetuate societal problems’ in the humanitarian sector.