Blog

From transparency to metrics: Measuring corruption in government contracts

The importance of public procurement around the world

Public procurement is the regulated process through which governments and other public entities purchase goods, works, and services. Understanding public procurement is central to understanding what governments do and when they spend taxpayers’ money in corrupt ways.

Public procurement spending represents about one-third of government spending of high-income countries, and an even higher share among low- and middle-income countries. Given the sums involved, the technical and legal complexities, and the wide discretion of public officials to define unique projects, corruption in public procurement is widespread – in countries of both high and low integrity. In addition, government contracts tend to be high-value – with many falling into the tens-of-thousands-of-dollars bracket – representing concentrated opportunities for extracting rents, making them the ideal target of high-level corruption by the rich and powerful.

The data revolution in public procurement

Offsetting the attractiveness of public procurement for the corrupt, there are strong and surprisingly often enforced expectations of competition and transparency. Even in highly corrupt countries, public procurement publication portals exist and contain a reasonable amount of useful data (see the World Bank’s compilation of portals, for instance). This makes public procurement one of, if not the most transparent government functions globally.

Moreover, such detailed contract and tender-level data describe real government action, rather than mere perceptions or ‘cheap’ talk: actor behaviour rather than laws and regulations. This makes it possible not only to understand where corruption risks lie but also which interventions work in which context (for a review of what works in public procurement see Fazekas and Blum 2021).

Such widespread transparency of micro-level public procurement data enabled the team at the Government Transparency Institute to compile a globally unique government contracting dataset, including a range of corruption risk indicators: the Global Public Procurement Dataset (GPPD). The GPPD covers 72 million contracts from 42 countries between 2006 and 2021, including seven individual corruption risk indicators:

- single bidding

- non-open procedure types

- no call for tenders published

- short advertisement period

- short decision period

- supplier tax haven registration

- high spending share of supplier

While the data varies by country and period, depending on what is published by governments, each record typically contains information on who contracts with whom (buyer and supplier data), contract values, and product information. They also typically contain a host of process information, like the procedure type used (eg open bidding, invitation-only tender, direct award without competition) or the deadline for submitting bids.

These variables enable users to calculate a wide variety of risk indicators and validate them using statistical methods. Examples of corruption ‘red flags’ that have been validated in GPPD include: single bidding on otherwise competitive markets; non-open procedure types; and suppliers registered in tax havens.

Figure 1. Global Public Procurement Database (GDDP) country coverage

Credit: Mihály Fazekas, Bence Tóth, Aly Abdou, and Ahmed Al-Shaibani by-nc-nd

With 42 countries covered, the GPPD is impressive at first sight. However, data quality varies considerably by country and period. Crucially, many countries’ data scope is limited, that is they only publish a fraction of their total public procurement spending in readily available, centralised public procurement portals. Some countries’ data coverage is very low, with around 10–20% transparently published (eg Germany, India, or Uganda), while other countries’ data coverage is nearly universal (eg Paraguay, Romania, or the UK). Accuracy of data is also problematic in many countries, for example due to high rates of missing data for key variables like contract values or the names of suppliers.

The transformational impact of data for addressing corruption in public procurement

Public procurement data has the potential to fundamentally transform how societies control and manage corruption, even if this data suffers from a range of quality problems. While we all would love to have perfect data quality, in reality no dataset is perfect and different data errors impact on different kinds of analytical goals. For large-scale policy analysis and academic research, some noise is typically only a minor problem because estimates across millions of records are inherently a little noisy, though averages remain approximately correct. For investigations (audits, criminal investigations, journalistic investigations, etc.), data errors are more problematic.

Still, readily available public procurement data and corruption risk indicators offer lots of tell-tale signs of wrongdoing to start from, though all data needs to be thoroughly verified and additional information collected. For instance, public procurement data can be linked to other datasets, both for improving data quality (eg adding company registry details from a linked dataset) or for extending corruption risk analytics to additional risk types (eg suppliers’ ownership risks or suppliers’ political connections).

Examples of GPPD in use – and its impact

GPPD represents merely one stage in the long journey of the Government Transparency Institute to make public procurement data and indicators widely available and usable for anti-corruption action in both investigations and policy analysis. The dataset has already been put to effective use many times, and we expect it to continue as an important tool.

European GPPD data – made easily accessible on the opentender.eu portal – has been used as a starting point for corruption investigations both by law enforcement and civil society. The structured investigative and reporting process set up by iMonitor guided civic monitors in Italy, Lithuania, Romania, and Spain towards high-risk tenders and organisations. They submitted freedom of information requests to gather additional information on potential corruption risks and also to verify and complete the publicly available tendering information.

Overall, about 100 contracts, worth a total of over 140 million euro, were monitored in depth by volunteers from the community, leading to criminal investigations and administrative action, and also contributing to the wider dialogue between public buyers and local stakeholder groups. An important takeaway here is that the GPPD and opentender.eu are complex tools, so thorough training and user-friendly interfaces are needed if their data and risk indicators are to be useful in contract monitoring.

GPPD has also served as a crucial input into policy analysis and the monitoring of public procurement markets. For example, the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy (DG REGIO) relied on opentender.eu data and corruption risk indicators for tracking governance quality at the regional level for several years (see the seventh, eighth, and ninthreports on economic, social and territorial cohesion). These indicators make it possible to track the evolution of corruption risks on a granular level, and examine changes over time in a single region of a country, rather than merely documenting general patterns.

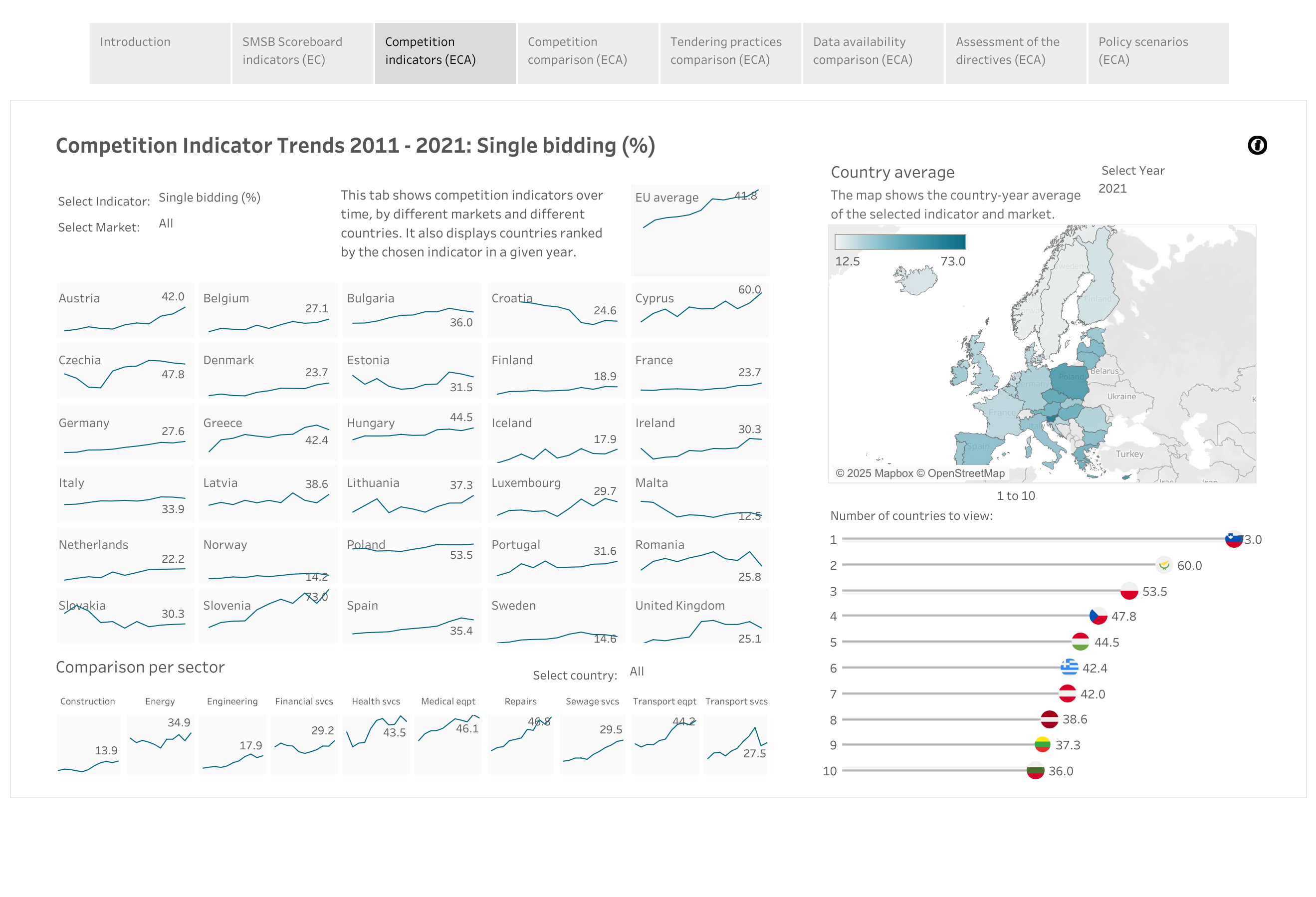

Similarly, the European Court of Auditors made use of opentender.eu data for tracking competitiveness in European public procurement markets. They found that competition is declining across the EU, a trend that is reflected in increasing corruption risks such as higher single bidding rates (see Figure 2), and one that is now widely recognised.

Figure 2. European Court of Auditors: The growth of single bidding across Europe, by country and by market sector

Credit: European Court of Auditors by-nc-nd

The future of the GPPD

Data collection for the GPPD is ongoing at the Government Transparency Institute, including the addition of more countries and more recent years.

Check for updates at https://www.govtransparency.eu/category/databases/ and https://opentender.eu/start.

Anti-corruption measurement series

This blog series looks at recent anti-corruption measurement and assessment tools, and how they have been applied in practice at regional or global level, particularly in development programming.

Contributors include leading measurement, evaluation, and corruption experts invited by U4 to share up-to-date insights during 2024–2025. (Series editors are Sofie Arjon Schütte and Joseph Pozsgai-Alvarez).

Blog posts in the series

- One year on: The Vienna Principles for the measurement of corruption (Elizabeth David-Barrett) 2 Sep 2024

- Measuring progress on Sustainable Development Goal 16.5 (Bonnie J. Palifka) 1 Oct 2024

- Pitfalls in measuring corruption with citizen surveys (Mattias Agerberg) 11 Nov 2024

- Decoding corruption: using the DATACORR database to design better survey questions (Luís de Sousa, Felippe Clement, Gustavo Gouvêa) 25 Nov 2024

- Can we standardise global corruption measurement? (Salomé Flores Sierra Franzoni) 12 Dec 2024

- Assessing the quality of corruption surveys for SDG 16.5 monitoring and beyond (Giulia Mugellini) 27 Jan 2025

- The Unbundled Corruption Index (UCI): Prototyping a multi-dimensional measure (Yuen Yuen Ang) 4 Mar 2025

- Reading the future, meaningfully: The Corruption Risk Forecast (Alina Mungiu-Pippidi) 31 Mar 2025

- (This post) From transparency to metrics: Measuring corruption in government contracts (Mihály Fazekas) 21 May 2025

Sign up to the U4 Newsletter to get updates, or follow us on Linkedin.

Disclaimer

All views in this text are the author(s)’, and may differ from the U4 partner agencies’ policies.

This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)